Apr 10•16 min read

Q1 2023 STX Mining Report

As of Apr 1st 2023; Stacks Block 100,500; BTC Block 783,418

by @mattyTokenomics

Introduction

Stacks uses a unique consensus mechanism called Proof of Transfer (PoX) through which the Stacks chain ultimately settles to the Bitcoin blockchain. PoX is conceptually similar to Bitcoin's PoW. In PoW, miners spend electricity for a proportional chance to win a BTC block. In PoX, miners spend BTC (recycled electricity) for a proportional chance to win a STX block. Since mining STX involves sending native BTC transactions on the BTC chain, the very act of mining STX is the act of writing Stacks’ history onto the BTC chain itself.

In other words, via PoX, there is no other way to add transactions on to the Stacks chain history other than to write that history to BTC’s chain.

Settling to BTC's chain means Stacks inherits much of Bitcoin's security and immutability, and the upcoming Nakamoto release will mean that Stacks inherits 100% of Bitcoin’s security. This means that to re-org the Stacks chain’s history would require a re-org attack (>50% attack) on Bitcoin itself. Until that release, the decentralization of Stacks mining itself has implications for security, and following the release, MEV and other concepts of Stacks mining will still be relevant for sBTC (more on that in a moment).

If you’re interested in the finer details of PoX, how STX transactions settle to Bitcoin's chain, and Stacks' attack vectors (pre-Nakamoto release), you can read this PoX Twitter thread.

The BTC spent by STX miners in the PoX consensus mechanism is distributed to stackers, generating a native yield for holders of STX distributed in native BTC. The decentralization of STX stackers plays the primary role in the security of sBTC, since they maintain the decentralized threshold signature wallet that controls non-custodial, programmable BTC on the Stacks chain, sBTC.

sBTC makes native BTC programmable without requiring trust in any centralized custodian, or federated network of centralized custodians, and without requiring an alternative L1 chain or bridge which does not ultimately settle to, and inherit security from, the Bitcoin chain itself (for example tBTC on ETH and BTC.b on AVAX both introduce additional chain specific security dependencies). You can learn more about sBTC in particular from this sBTC Twitter thread or from the sBTC whitepaper.

This quarterly stacking report covers the current state of Stacks mining and is not intended as a deep dive into how PoX, mining, or stacking work. For more in-depth reports on STX mining decentralization see this initial in-depth STX mining report from July 2022 or this SIP forum post for mining improvements.

You can also read the Q4 2022 STX Mining Report here.

Unless otherwise specified, this report covers the time periods below

Past Year: Q2 2022 - Q1 2023

Past Quarter: Q1 2023

1. Block Frequencies

While STX blocks aim to settle 1:1 to BTC blocks, and BTC blocks settle on average every 10 minutes, events such as flash blocks mean that occasionally there are BTC blocks with no STX blocks. As a result, STX blocks generally take slightly longer than 10 minutes.

Work in progress to bring subnets to Stacks, mainnet expected later in 2023, which combine a) the security benefit of settling to the Bitcoin chain each BTC block, with b) the speed benefit of transaction finality in 1/10th the time.

Past Year Minutes per STX Block: 11.4

Past Quarter Minutes per STX Block: 11.62. Number of Unique Miners

Not every miner mines every block - this measurement looks at the number of unique addresses that have mined STX in at least one block during the time period in question.

Past Year Unique STX Miners: 80

Past Quarter Unique STX Miners: 343. Number of Typical Miners & >50% attack Miners

When people think of decentralization for mining, they typically think of two things:

The total number of miners in an average block

The number of miners required to execute a >50% attack (51% attack) in an average block

As a point of comparison, the largest 2 mining pools of Bitcoin mined more than 50% of blocks in December 2022, meaning (in theory) it would take 2 parties to collude. Recent stats of BTC mining pool hash power shares show a similar picture, with 2-3 pools required to collude to reach >50% of all pool’s hash power.

These figures are comparable to Stacks’ own figures. That said, recent analysis of block-by-block mining production has found that more than 1 of the miners mining Stacks seem to controlled by the same entity, as they sometimes ignore previous valid blocks produced by other miners to create their own.

Ongoing work on decentralized mining pools would add more competition, reducing this impact, and further improvements currently being discussed to prevent miners ignoring previous blocks would further help rectify this.

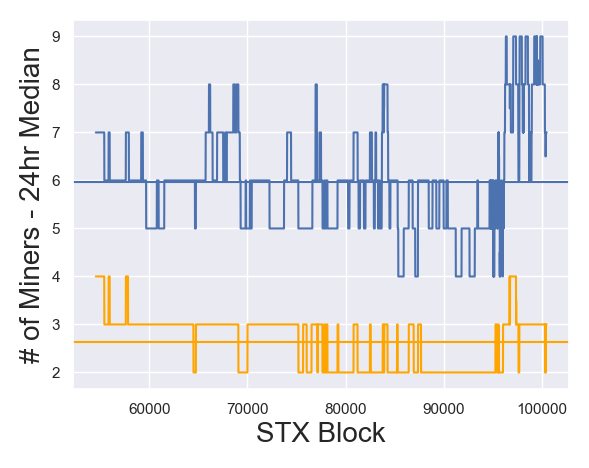

In BLUE, the total number of miners per block.

In ORANGE, the number of miners required for a >50% attack.

Past Year Total Miners per Block: 6.0

Past Quarter Total Miners per Block: 6.2

---

Past Year Miners >50% Attack per Block: 2.6

Past Quarter Miners >50% Attack per Block: 2.5During the past quarter, STX mining has become relatively more centralized. This is to be expected during a bear market for both BTC/USD and STX/BTC, but is comparable to Bitcoin’s degree of mining centralization, and improving mining decentralization is being taken seriously by the Stacks community. You can join the conversation here.

4. Gini Coefficient of Miner Activity

The Gini coefficient is a popular measurement for quantifying inequality. It ranges in value from 0 (perfect equality) to 1 (maximum inequality). Looking at the Gini coefficient of miner's commitments is another way of expressing the relative balance (or imbalance) of small miners vs large miners.

For example, if every STX miner was the same size, the Gini value would be 0. But if mining has heavily dominated by just a handful of miners, the Gini value would approach 1.

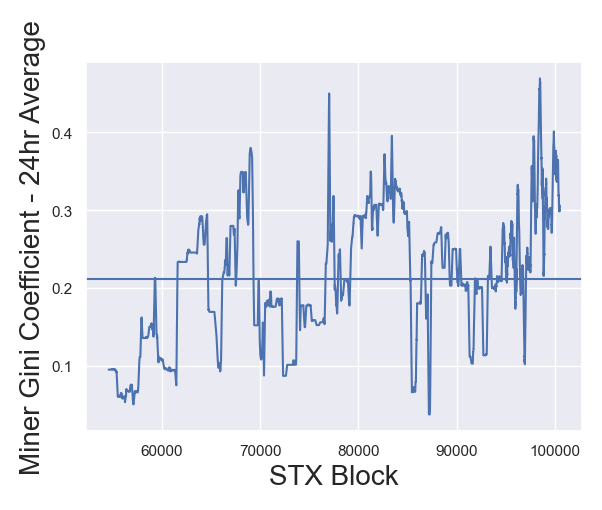

In BLUE, the Gini coefficient of miner commitments per block.

Past Year Average Gini Coefficient: 0.211

Past Quarter Average Gini Coefficient: 0.241The increasing Gini coefficient in the past quarter, also reflects less miner decentralization. Want to help improve things? Get up to date on the latest proposals and involved here.

5. Number of Txs per Block

The number of transactions in an average block indicates the demand for transactions to be included in STX blocks. Just like BTC mining, STX miners earn revenues from a block reward, and from transaction fees. While fees (which we'll look at next) tell the most direct part of the story, tracking number of transactions can show if changes in fee revenue are healthy (due to more chain usage) or unhealthy (fees increasing due to congestion or other issues even though demand is not increasing).

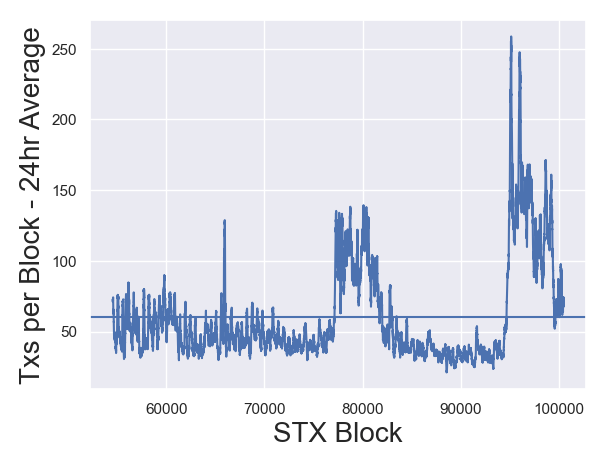

In BLUE, the total number of processed transactions per block.

Past Year Average Txs per Block: 60.5

Past Quarter Average Txs per Block: 80.5It remains promising for Stacks overall, that despite a bear market in BTC/USD and STX/BTC prices, usage of the STX chain has remained higher than historically, even after falling from the spike in activity caused by a flurry of BNS '.btc' domain name purchases.

6. STX Miner Fees as % of Total Rewards

Just like BTC miners, STX miners earn both a) a fixed block reward and b) a variable amount of fee revenue from the gas fees users of the network pay.

While gas fees are not inflationary, issuing block rewards to miners is inflationary. Miners need an incentive to mine so rewards to miners must come from either:

Pay miners inflationary block rewards and gas fees (ex. Monero)

Pros: Always an incentive to mine

Cons: Some level of inflation - though it can be set to a minimal amount

Pay miners gas fees with no block rewards (ex. what Bitcoin plans to do)

Pros: Theoretically no inflation

Cons: Variable incentives to mine that depend of network activity, and if there are not enough gas fees to incentivize mining, the network’s security is at risk

Pay miners only inflationary block rewards, and offset by burning gas fees (ex. Ethereum)

Pros: Always an incentive to mine, and if high enough levels of activity, no inflation or even deflation

Cons: Complexity

BTC plans to fade out block rewards entirely (in about 2140), though the necessity of "tail emissions" for Bitcoin still a topic of debate, at least some (albeit theoretical) evidence that fees can never fully replace the need for block rewards.

Regardless, the more revenues miners earn from fees as opposed to from block rewards, the more sustainable the chain is without requiring higher levels of inflation from block rewards.

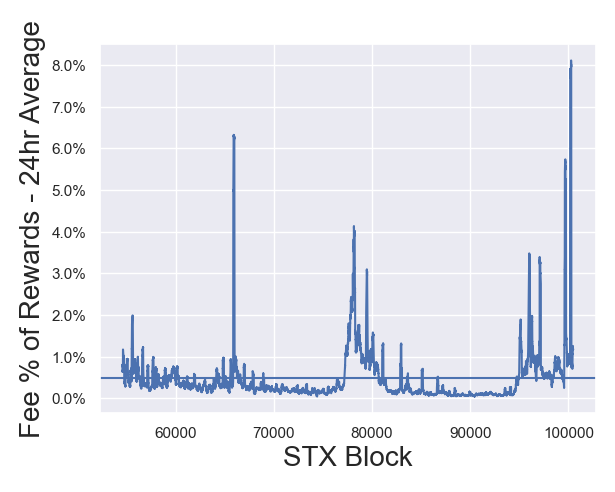

In BLUE, the percent of total miner rewards earned from gas fees. A value of 50% would represent miners earning just as much in gas fees as they earn in inflationary block rewards.

Past Year Average Fees as % of Rewards: 0.49 %

Past Quarter Average Fees as % of Rewards: 0.64 %There may be early signs of higher fee revenues to STX miners, but significant variance is present around periods of high chain usage and congestion. It remains to see if this trend will continue.

There are quite a lot of high-impact releases in the near future of Stacks' roadmap that stand to enable much greater levels of network usage, including the introduction of sBTC, whose peg-in and peg-out transactions on the Stacks chain may increase both recurring network transactions and total transaction gas fees.

7. Miner Aggregate Profit Margin

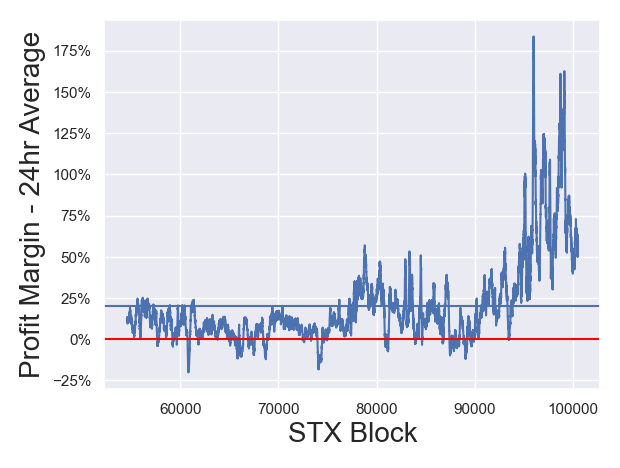

While an individual miners' profit ultimately depend on a variety of specific factors including how they mine, when they mine, other miners’ behavior's, market forces, and random chance, we can objectively quantify the aggregate profit margin that miners in total are earning.

To mine STX, miners spend sats (BTC), and earn STX in block rewards and gas fees. By denominating their STX rewards in sats (BTC) at the market value of the time they earn the rewards we can track profit margins as:

(Sats Rewards Earned - Total Sats Spent) / Total Sats Spent

For example a value of 10% indicates that for every 100 sats spent on mining (including BTC gas fees), miners are earning 110 sats in rewards.

In BLUE, the aggregate profit margin miners earn per block.

Past Year Average Profit Margin: 19.9%

Past Quarter Average Profit Margin: 48.6%Overall, profit margins have been exceptionally high for miners, starting to trend up sometime around block 90,000, and peaking as the STX token itself appreciated in BTC terms.

This is a promising sign for the ongoing work on decentralized mining pools - it demonstrates there is plenty of room for new miners to also mine profitably. That said, the aggregate profit margins are inflated by two new forms of MEV, which are good for miner profit margins, but not necessarily good for the aggregate network.

BTC Miner MEV Issue

Since STX is mined by sending Bitcoin transactions, entities which already mine Bitcoin can win a given Bitcoin block, and exclude all other Stack miners’ Bitcoin transactions from that block. This effectively ensures that if a Bitcoin miner wins a Bitcoin block, they can also win the corresponding Stacks block without any competition from other Stacks miners. To repeat, this only applies for the corresponding Bitcoin blocks they win - overall there is still mining competition over Stacks blocks and over the Bitcoin blocks they settle to. But this does represent a form of MEV, increasing miner profits while decreasing the yield available to stackers. You can follow the discussion on solutions to minimizing this MEV here.“Orphan Block” MEV Issue

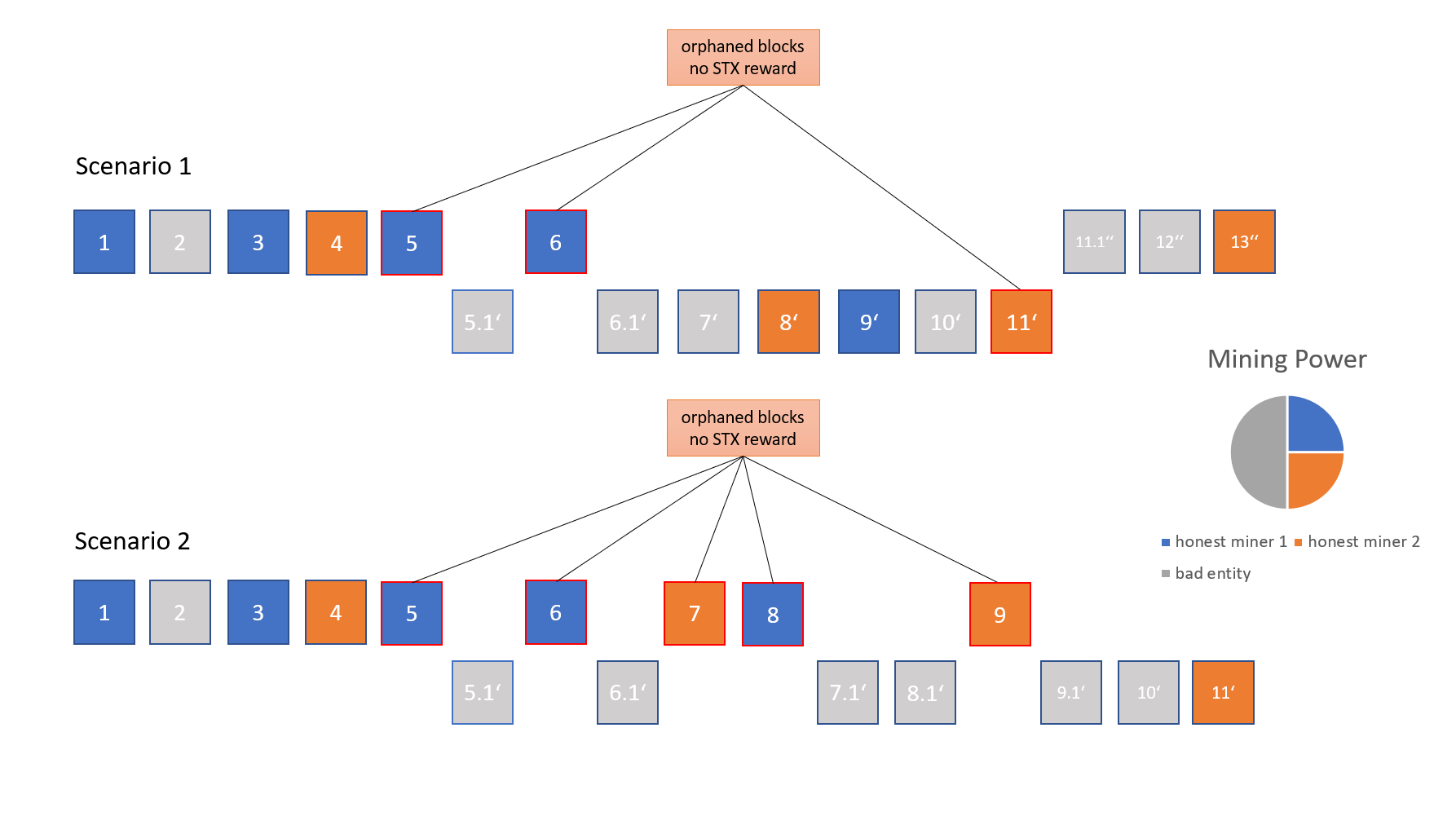

The other issue, not to be confused with the BTC Miner MEV Issue, is that a large miner is ignoring blocks previously created 1-3 blocks ago and then building their own longest chain which now excludes those blocks, thus orphaning them.

The latest blocks to be mined being orphaned in a longest-chain consensus model is not itself an unexpected phenomenon. It occurs even in Bitcoin for example, which is why you generally need to wait something like 3-6 blocks for confirmation of deposits. Occasional changes to the last 1-2 blocks in a longest chain blockchain are bound to occur. However in this case, the miner’s size advantage is exacerbating the profit they can make by acting selfishly. Increasing the mining activity by “honest” miners like decentralized mining pools would go far to counter this, and you can follow the discussion to evaluate other ways to minimize this impact here.

If you are a BTC miner that would like to more about STX mining, please get in touch via Twitter, Discord, or Telegram.

8. Miner Profit Margin Distribution

One ongoing potential concern, especially given the two recent forms of MEV discussed above, is that even if aggregate profit margins are high for miners, those profits are accruing disproportionately to a small number of miners.

For example, it’s alleged multiple times in the previously linked forum discussion, that as a result of these MEVs, particularly, the “Orphan Block” MEV Issue, smaller miners can not compete. One specific case was STX block 99,153 which was originally mined by SP11SERAP17NV2F1PGHX6S9RGPE3CSZAE3B6Z9JW7. But this block was ignored by miner SP1G7E460C2NX1GQ3YRZKCXAADMYY20TKV0XD1R0K, who orphaned SP11’s block, and created a longer chain by mining block 99,153 and 99,154 with a different address (SPFC8JCHPFWG3QQZEVRQAJCM2ZF3QVNZGKYPGB6T) supposedly controlled by the same entity because it ignored SP11’s orphaned block, thus “collaborating” with SP1G.

To analyze this, we can break down the observed profit margins of 12 addresses for known/suspected MEV miners vs other miners.

Past Year MEV-Miner Profit Margin: 67.8 %

Past Year Normal Miner Profit Margin: 14.6 %

Past Quarter MEV-Miner Profit Margin: 74.2 %

Past Quarter Normal Miner Profit Margin: 43.0 %As expected, MEV miners are more profitable on average. However, non-MEV miners are still profitable overall, and in fact, still had record-level profit margins for mining in Q1 2023.

Simply put, while miners not taking advantage of MEV are at a disadvantage, the theory that this disadvantage is so pronounced that it makes it impossible for honest miners to participate is not supported by the current evidence. This bodes well for additional miners to come in, including decentralized mining pools, while the ongoing community discussions consider more direct approaches to minimizing the impacts of MEV.

9. Percent of Blocks With Only 1 Bidding Miner

Another way to visualize and quantify the prevalence of BTC Miner MEV specifically is to look at the percentage of blocks that are won only by one single miner. This can occasionally happen by random chance, so assuming 100% of these cases are MEV-related gives an accurate picture of a worst-case assumption.

Past Year % Blocks 1 Miner: 2.6 %

Past Quarter % Blocks 1 Miner: 6.9 %Last quarter, about 7% of all blocks were mined with only one miner bidding on the block. If we assume every single case of this is MEV related (it can and will sometimes happen randomly due to BTC network congestion even without MEV), we can infer that this MEV is reducing rewards to stackers by approximately 7% since these blocks are paying virtually zero yield whereas they would be paying an average yield.

To avoid misinterpretation, for a given APY of 10%, this reduction in rewards would roughly translate into a reduced APY of 9.3%, all else equal (it should not be interpreted as reducing a 10% APY to 3%).

10. BTC (or USD) Required to Breakeven for 1 Cycle

One of the biggest deterrents to new miners starting to mine STX is the initial capital requirements to do so. This is because miners of STX must not only bid native BTC for a chance to win each block, but also spend BTC gas fees on those native BTC transactions each block. These costs can add up for individual miners over the course of a full STX cycle (2,100 STX blocks).

For example, if BTC gas fees are 5,000 sats per block (0.00005 BTC per block), then bidding on each block in a 2,100 block cycle would cost 0.0105 BTC in gas fees alone. Mining profitably would require spending even more BTC, as the profits of mining must overcome the “fixed cost” of Bitcoin network gas fees.

Past Year BTC Required to Breakeven 1 cycle: 0.77

...in USD at current BTC/USD: 22,028

Past Quarter BTC Required to Breakeven 1 cycle: 0.35

...in USD at current BTC/USD: 9,931Work is in progress to enable non-custodial mining pools (2.1 adds support for several critical requirements), but for now, trustless mining pool are not yet possible. While capital requirements have come down considerably for new miners to breakeven (dropping more than 50% since Q4 2022 in BTC terms), mining profitably above breakdown would require even more capital than required to breakeven.

This cost remains a large deterrent to additional miners joining - a specific deterrent that non-custodial mining pools will go far to address.

Conclusion

Q1 2023 has still been an overall bear market for crypto, but was something of a bullish resurgence for Bitcoin with the interest in Ordinals, and with Stacks given the market opening its eyes to the opportunity of Bitcoin layers.

Challenges for STX mining remain, including two new forms of MEV, and while these should be downplayed, they also represent that Stacks is gaining more traction and attention where MEV opportunities are now large enough to be sought ought, whereas before the ecosystem often went overlooked.

Additionally, contrary to opinions, the actual evidence does not support the conclusion that all other miners can not mine profitably. Current profit margins available to sufficiently capitalized honest Stacks miners are larger than they ever have been before in mining history.

A number of significant features from the roadmap are expected in 2023 such as Stacks 2.1, subnets, and sBTC, which contain necessary features to support non-custodial mining pools and facilitate higher network usage than ever before.

If you are interested in mining STX or improving decentralization and security, please get in touch or join the community conversation.

Appendix

Author

mattyTokenomics has more than a decade of experience designing economic models for multi-billion AUM hedge funds and VC funded startups. In the Stacks ecosystem, he has worked with Trust Machines, Stacks Foundation, Mechanism, ALEX, Zest, NeoSwap and others on their tokenomics and consensus mechanisms - including for Stacks itself. He has authored approved community proposals for DeFi protocols Arkadiko and ALEX, mentors founders at the BTC Frontier Fund and is an occasional angel investor.

Get in touch at https://linktr.ee/tokenomics

Additional Resources

More details on PoX, Stacks security, attack vectors, and settling to Bitcoin

More detailed report on STX mining decentralization and how to attract additional miners

SIP (Stacks Improvement Proposal) forum discussion on STX mining, and possible proposals to increase decentralization:

https://forum.stacks.org/t/miner-centralization/13217

Data Sources

Mining commits and coinbase rewards: https://app.onstacks.com/

BTC transaction gas fees: https://www.blockchain.com/api/blockchain_api

STX transactions and gas fees earned per block: https://stacksonchain.com

Market prices for STX and BTC: https://www.coingecko.com/api/documentations/v3