Feb 21•5 min read

Still Thinking About Coronavirus and Stagflation

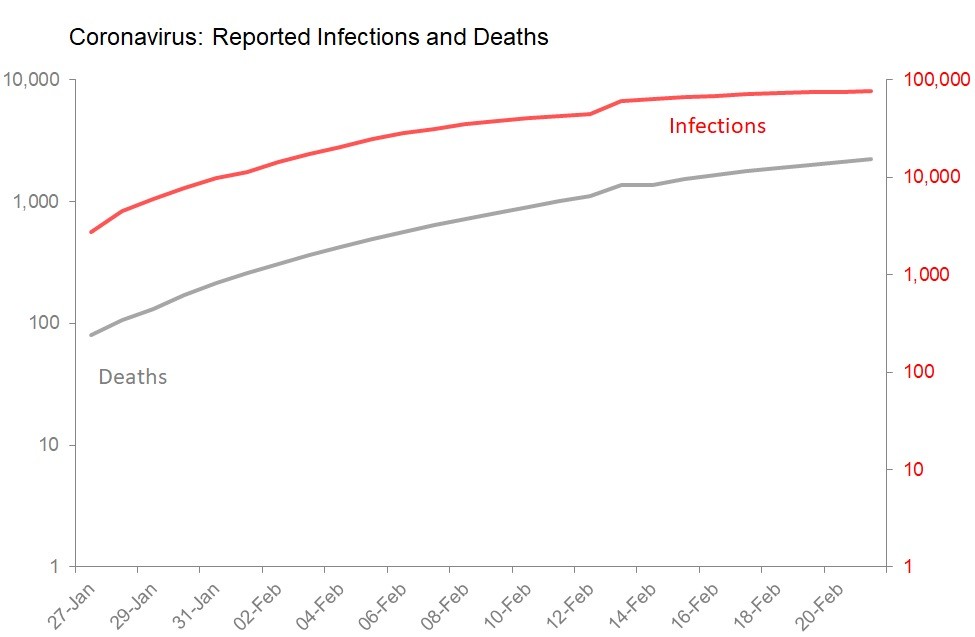

Two weeks ago - before I got struck down, ironically, by norovirus - I suggested some ways of thinking about coronovirus. Two weeks down the line, there is more to say. Let's start with the positive: if the publicly available data on infection is correct, then it looks as if the feared global pandemic is not with us. This is made clear simply by tracking infections on a log basis, rather than a linear basis. When viewed on a log basis, the prospect of millions of infections, and therefore hundreds of thousands of deaths, seems remote.

The problems start with the big qualifier: 'if the publicly available data on infection is correct'. The data I'm using comes from Pharmaceutical Technology.com, which has both the incentive and the industry position to get this right. It is running a timeline updated daily which tracks infections, deaths and recoveries. I have no reason to believe they are not doing a good job.

Nevertheless, there are three factors which might break that qualifing 'if'.

First, to be blunt, knowingly or ignorantly China's account might be wrong. Since China has a massive interest in damping down both international and domestic concerns about how it is handling the outbreak, its authorities may be knowingly minimising the number of infections. One would expect any under-reporting and/or under-estimation to start right at the bottom and work its way right up to the top.

Local doctors under pressure from local politicians to secure 'victory' in the war on the virus may be deliberately mis-diagnosing and mis-reporting

Local city politicians under pressure from provincial politicians desperate to secure 'victory' revising down infection counts before they are passed up to provincial level.

Provincial leaders anxious to secure Beijing's approval being keen to report 'no problem here'.

And finally, in Beijing, everyone will have the keenest incentive to assure Xi Jinping that he personally is securing victory.

The problem may not be that China's leading politicians are trying to deceive. Indeed, China may be really trying to get it right. But China's system of scary incentives tilts players at all levels towards deceptive behaviour. China is emphatically not a system which rewards whistle-blowers. Even with the best intentions, China is unlikely to be able to gather the data cleanly.

Second: to the extent that China has controlled the outbreak, it has done so by shutting down the economy. This cannot last. The draconian measures taken to put hundreds of millions in quarantine are incompatible with social and commercial life as we know it. In some ways, the emergence of the virus over the New Year holiday period is a stroke of luck, since outside transport and restaurant sectors, economic activity is expected to grind to a halt during the holiday, and companies are well used to managing this interruption. Putting the country in quarantine during this period is not, then, the immediate economic challenge it would be at other periods. But if that quarantine is extended, that piece of logistical good luck will have run out already. At some point, the economic costs of fighting the infection in this way will become intolerable. That's the point at which the outbreak can be expected to find its second wind.

Third: India and Indonesia are immune? So far, Indonesia has no reported cases of coronavirus, and India has three. These are either remarkable triumphs of public health policies; extraordinary luck; or rubbish. If it turns out that the remarkable immunity of India and Indonesia is a mirage, these two massive population centres may yet find themselves playing a central role in the global spread of the disease.

It is hard to believe that no combination of these three factors will not kick in and undermine the good news shown in the first chart. That means that the supply shock, of which we are getting merely the first taste, is likely to get much worse in the short to medium term.

I do not usually give much credence to Markit's monthly PMIs, because the indexes provide no guide at all to the 'hard data' of industrial and services output which emerges months later (when the PMIs are forgotten). Nevertheless, February's data from Japan, Europe and the US contains some quite dramatic testimony about the strain supply chains are under. Japan's manufacturing PMI fell to 47.6, the weakest result since December 2012, with the biggest drag being a fall in new orders. In Germany, the manufacturing PMI actually rose to a 13 month high of 47.8 - but don't be fooled, almost half of the monthly gain was attributable to a lengthening in (Chinese) supplier delivery times. In the UK, stocks of inputs fell at the fastest pace in more than seven years, and the drop in supplier delivery performance was the worst the survey has recorded since its debut in 1992. In the US, companies reported a slowdown in output growth (index at 50.6 in Feb vs 52.4 in Jan) which respondents blamed, in part, on delays in deliveries.

So far, although my Inflation Shocks & Surprises chart is already flashing red, the February surveys also tell us that the scramble to source and secure deliveries has not yet resulted in prices being bid up. However, this should certainly be expected in the coming weeks and months.