Jan 20•9 min read

China's 2019: Treading Water, Not Waving, Not Drowning

China's data-drop this Friday closed the book on 2019 and initiates a couple of months of near data-silence - we won't be getting substantial updates until mid-March. So let's take stock.

I have been watching China's economy for three decades now (good grief!), and it's fair to say that 2019 was amongst the dullest year I've witnessed. My momentum indicators suggest as much: the measured momentum for both the industrial economy and domestic demand have meandered just above and just below trend respectively, whilst attempts to ginger up the economy by loosening monetary conditions have been at best half-hearted.

Worse, 2019 was a year in which none of China's identified problems were addressed, so no substantial progress was made in solving them. Issues of excessive leverage and associated interest-rate vulnerability, the economic efficiency of the financial system, and the long-term erosion of the government's tax base, none of these issues has been grasped, none rectified, and consequently the extent to which these compromise China's long-term prospects remains unchanged.

Although China's export industries did better than any of its Northeast Asia competitors/collaborators, raising its market share of NE Asia exports by 1.4pps to a record 61.2%, this export dominance is no longer sufficient to nullify longstanding structural problems, let alone rectify them.

The heart of these problems is two-fold:

an administrative state which is now increasingly neglecting or losing its ability to tax the economy in the way it needs to fulfil its broader social and strategic ambitions;

in the absence of fiscal firepower, it continues to rely on administrative 'guidance' backed up by a debt-oriented financial system which may, upon occasion, still be susceptible to political persuasion. But this alternative tends to impair the operational financial efficiency of the finance system, which in turn leads the economy to run at relatively high leverage ratios.

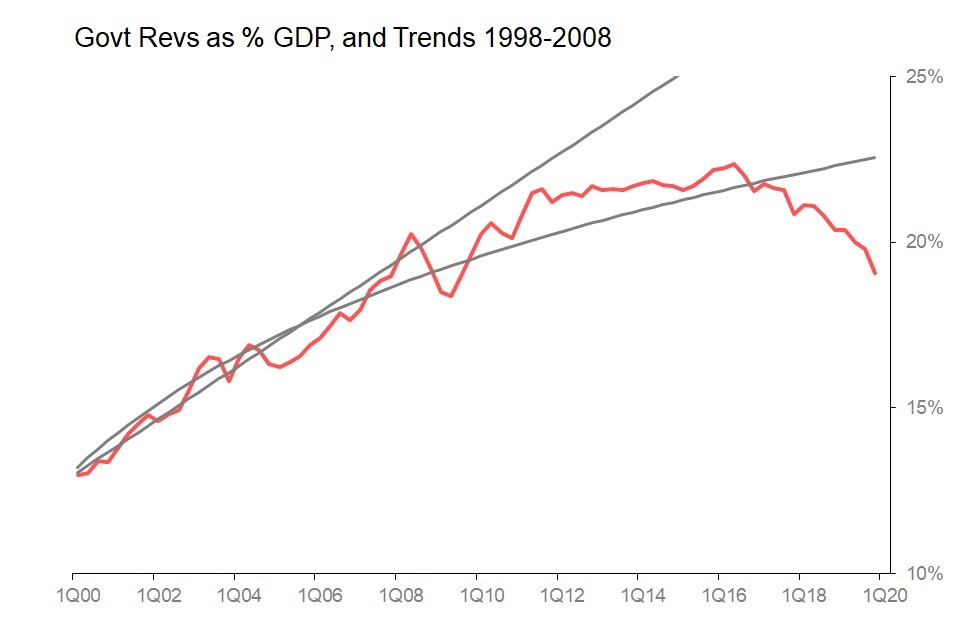

A useful entry point into this tangle is the relatively poor ability of the state to tax the economy. In the 12m to Nov 2019, govt revenues rose 3.7%, and I estimate they rose 3.8% for 2019 as a whole. If so, that cut revenues as a percentage of GDP to just 19.1%, which is the lowest its been since 2009, and down from a high of 22.4% in 12m to 2Q16. For the time being, the government has seemingly given up the attempt to strengthen its fiscal grip on the economy made so vigorously during the first decade of this century.

Just how long the government is prepared to continue to let things slide is unknown. Generally speaking, the problem is neither acknowledged or discussed publicly. However, the relative atrophying of the government's fiscal firepower means an increased reliance on debt financing both for the government itself and for its corporate clients and offshoots.

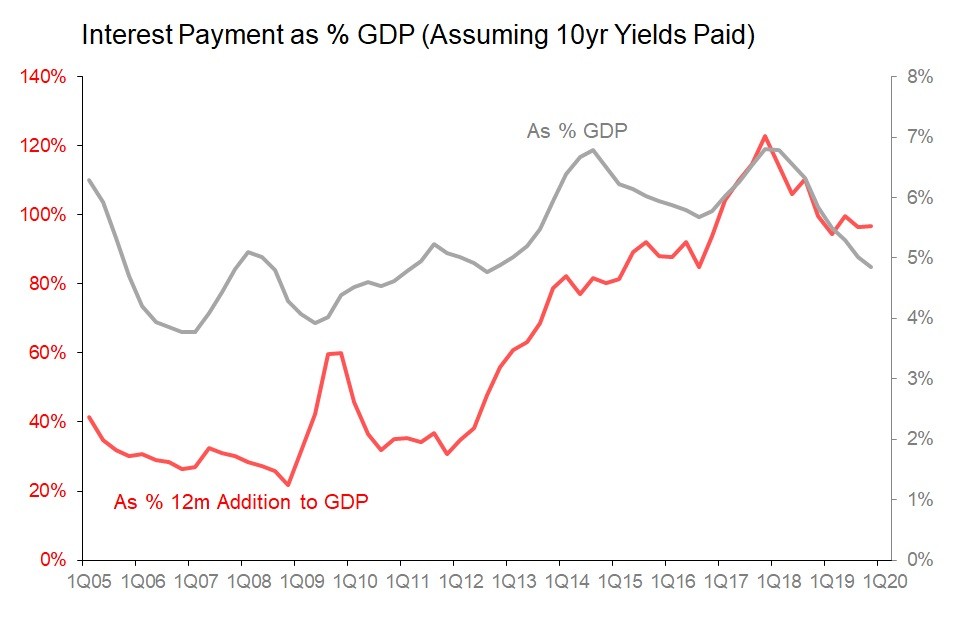

And so we come to the question of leverage. The broad count of domestic credit rose 10.4% in 2019 (vs 10.9% in 2018), lifting credit/GDP ratio to 215.2% up from 211.9% in 2018. If one used the broader 'aggregate social financing' tally, that would be 251.7% of GDP (vs 247% in 2018).

In other words, although the efforts of the last five years have roughly stabilized China's debt/GDP ratio, it has not reduced it at all.

This means that China's economy remains hostage to low interest rates. Even with 10yr bond yields averaging 3.17% in 2019 and even assuming that all domestic credit was paid at these low rates, interest payments alone on that debt would be equivalent to essentially the entire increase in nominal GDP. This has been the situation since around 2016, and without a substantial reduction in debt/GDP, this will not change.

A world of sustained low interest rates is as crucial to China as anyone else.

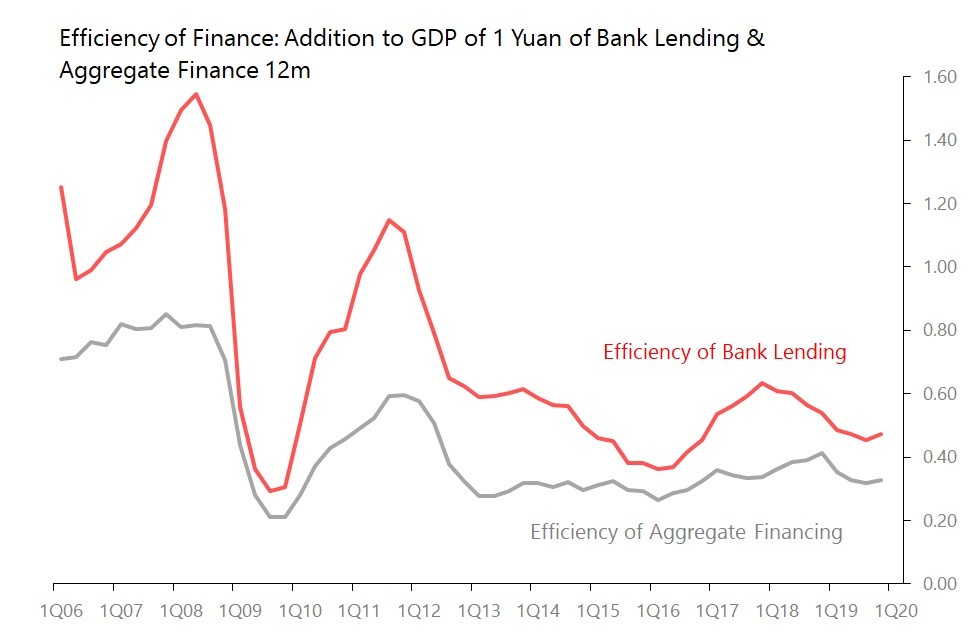

China can ease itself out of this situation only if the economic efficiency of finance improves: ie, it needs to get more bang for every buck of extra finance added to the economy. But here too, 2019 was a year wasted. During 2019, every 100 yuan in new bank lending was associated with a mere 47 yuan in extra nominal GDP - down from 54 yuan in 2018, and compared with a 10yr average of 61 yuan. Taking the broader 'aggregate financing' measure, every 100 yuan of this financing added was associated with 33 yuan of extra nominal GDP, down from 41 yuan in 2018.

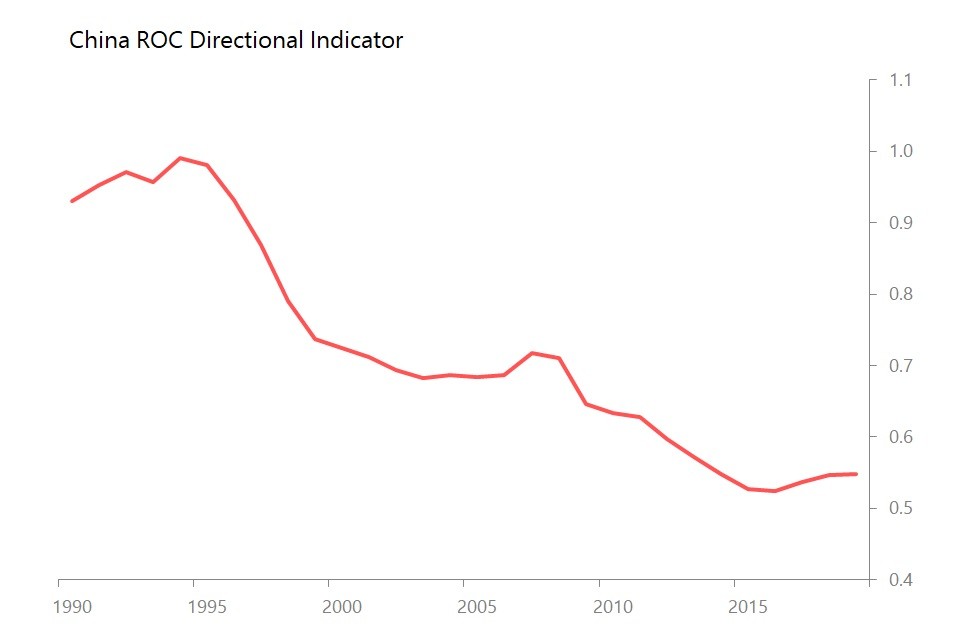

As the chart shows, the gains in efficiency initially squeezed out in the early stages of credit tightening have been given back, first because the squeeze was kept on so long that it impeded normal commercial operations, and then because it needed to be relaxed to deal with those consequences.

In short, China's attempt at disciplining its financial system into more economically efficient behaviour, which initially showed some promise, has failed and is failing.

What of the positives?

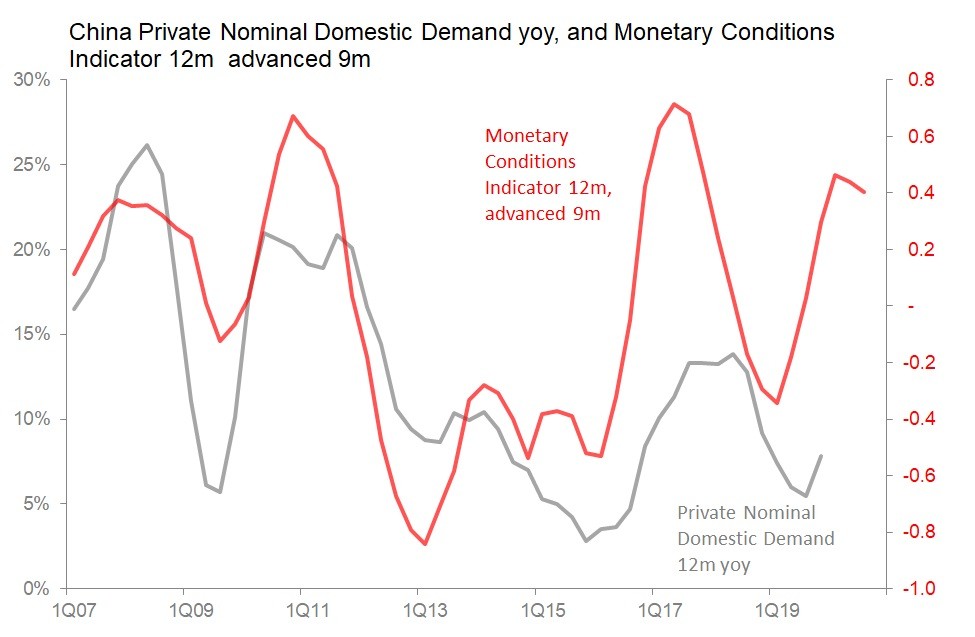

Early last year, I forecast that around the middle of the year, China's private nominal domestic demand (ie, nominal GDP less fiscal and trade balances) should begin to accelerate, albeit less dramatically than we have seen in previous cycles.

This was my central case, and it was broadly correct: the link between monetary conditions and private nominal domestic demand continues - it arrived slightly later than expected, but was, as also expected, weaker than previously. Growth in 12m private nominal domestic demand, as measured in the national accounts bottomed out at 6.6% in 3Q (one quarter later than I expected), and recovered to 7.6% in 4Q.

That's an anaemic upward inflection point, and although this recovery in private nominal domestic demand is likely to be maintained, it seems unlikely to be pushed much more vigorously next year, with the lagging positive impact of monetary stimulus peaking in 1Q20. Quite possibly, this is about as good as it's going to get.

I think China's return on capital directional indicator probably inched higher, and I think China's Kalecki profits probably outpaced nominal GDP growth for the first time since 2015. However, as we shall see, in both cases, the judgements are based on 'best-guess' estimates of crucial inputs, and the positive results are only fractionally so. It is only fair to warn that in both cases, the margins of possible error could quite feasibly erase or even reverse the conclusions I offer here.

Kalecki Best Guesses

I do not have enough, or good enough, data to do a proper estimate of Kalecki profits. However, it seems likely that 2019 saw a modest acceleration in the growth of Kalecki profits for the fourth year in a row, and that for the first year since 2015, profits probably slightly outpaced nominal GDP growth of 8.6%.

This conclusion is reached by the estimate of gross capital spending growth slowing to 8%, which would have cut the estimated growth of capital stock to 8.3% (vs 8.7% in 2018) and growth of net investment to 7.8% (10.9% in 2018). Other factors at work include a rising trade surplus (Rmb 2,981bn in 2019 vs Rmb 2,434bn in 2018), and a widening fiscal deficit (Rmb 4,233bn in 2019 vs Rmb 3,755bn in 2018).

Taken together these imply a rise in Kalecki profits of 9.7% (vs 9.2% in 2018), compared with a nominal GDP growth of 8.6% (vs 10.5% in 2018).

The final factor is the extent of household sector dissaving from income, which, judging from the quarterly surveys of income and spending, rose 8.7% (unchanged from 2018), essentially in-line with GDP growth.

Overall, then, Kalecki profits probably rose very slightly faster than nominal GDP.

Similarly, I think China's return on capital directional indicator probably ticked very slightly higher (ie, capital stock growth falling to 8.3%, nominal GDP falling to 8.6%. As with so many of the charts accompanying this analysis, the uptick is slight, the improvement so anaemic that they offer little if any firmer foundation for dealing with the underlying problems which were ignored this year.

The conclusion, then, is scarcely encouraging: 2019 was a year in which various compromises and back-trackings from efforts at fundamental reform kept the show on the road despite a modestly hostile external environment. However, all the problems remain, and the most recent attempts to grapple with them have been abandoned without producing significant results. China is treading water, neither waving nor drowning. There is no reason to expect 2020 to be any different.

Addendum - December's Data

Generally, December's news was slightly better than expected:

Industrial production rose 6.9% yoy, with a monthly movt 0.9SDs above historic seasonal trends. Manufacturing rose 7% yoy, with a bounce in SOE output (up 7% yoy in Dec vs 3.7% in Nov) offsetting a slowdown in private company output (7.1% yoy in Dec vs 8.9% in Nov;

Urban fixed asset investment recovered to raise growth for the year to 5.4% (vs 5.2% in Jan-Nov). Caveat: opaque changes in the base of comparison make it impossible to understand the headline numbers;

Capacity utilization rates rose to 77.5% in 4Q from 76.4% in 3Q, which was enough to raise the rate for 2019 by 0.1pp yoy to 76.6%. The sectors generating the improvement were oil & gas, up 2.9pps yoy to 91.2%; and iron & steel processing, which rose 2pps yoy to 80%;

December's survey of new property prices in 70 cities found price rising mom in a net 34 cities, up from 23 in November.

The remainder of China's December data contained no shocks, but was unremarkable: retail sales rose 8% yoy, electricity production +3.5%, exports +7.4%, imports +16.2%, and a US$46.8bn trade surplus; money M2 +8.7% yoy and new bank lending of Rmb1,140bn, with new aggregate financing of Rmb 2,042bn.

Net result: 4Q GDP growth was unchanged at 6% yoy, leaving 2019 GDP growth at 6.1%.