Jan 14•5 min read

About That 2021 US Rebound: Household Sector

The surprisingly bleak account of US consumer attitudes which surfaced in the NY Fed's December survey of attitudes has passed almost unseen. When I relayed the details in 'Bleak Expectations' earlier this week, I got some resistance: surely this reading conflicts with the widely-held expectation of a hearty post-Covid rebound in 2021 US?

Back in November, I took the view that we should expect to see a weakening in US data, relative to consensus or trend, emerging around the end of 1Q, as the first-round impacts of 2020's monetary and fiscal stimulation begin to wear off. So my expectations set for the US was probably already less optimistic than consensus. However, given that this is apparently a very minority view, it is worth taking a closer look at the elements of domestic demand that would be in play during the rebound. This is principally consumer and investment spending.

This first part concentrates on the household sector. But note at the outset that even if the signals from these are ambiguous or negative, there remains the possibility that further fiscal and monetary stimulus may yet over-ride them. But also bear in mind that the returns to fiscal and monetary stimulus are, in any case, likely to be diminishing in 2021.

On the face of it, there seems little need to explain the expectation that consumer demand is set to surge when the economy eventually feels that covid is under control. It seems obvious: demand has been unnaturally suppressed, and when that suppression is lifted, that pent-up demand will find release in a spending surge. But how obvious is that really?

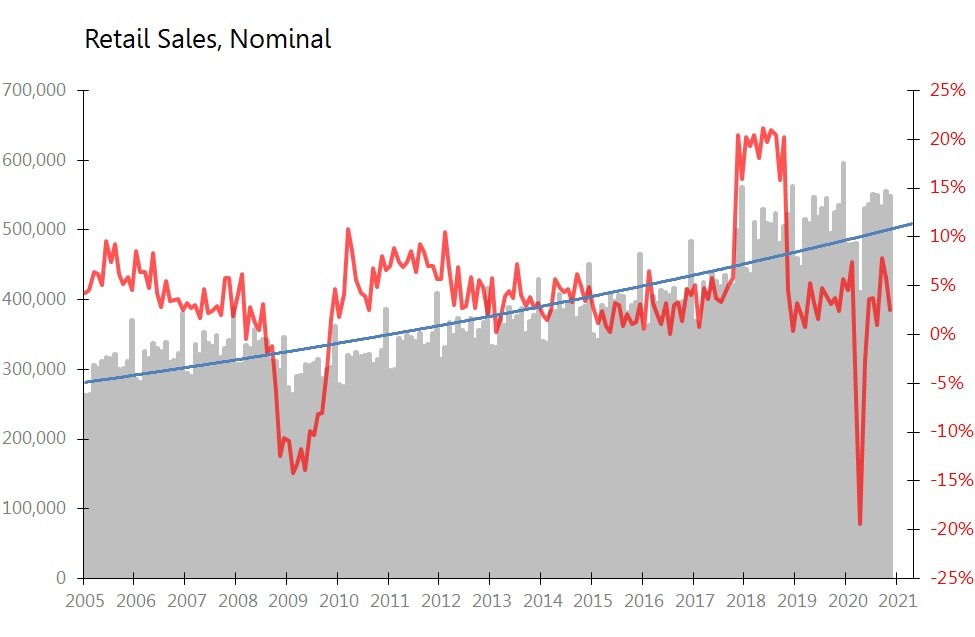

Let's look first at the most obvious are of potentially suppressed demand: retail sales. It turns out it is surprisingly difficult to spot the suppressed demand. It is true that sales plunged during the first wave of covid, with sales hit hard in March and April. Indeed, in April, sales were down 19.4% yoy. But the recovery was correspondingly rapid in May and June - so much so that in June sales were up 3.6% yoy. And the yoy gains have kept coming throughout the rest of the year. In fact, for much of the year, nominal retail sales have been growing, and at a level faster than long-term retail sales trends (log trend). The fact that retail sales are running substantially over-trend makes it difficult to argue that suppressed retail demand is about to be liberated in 2021.

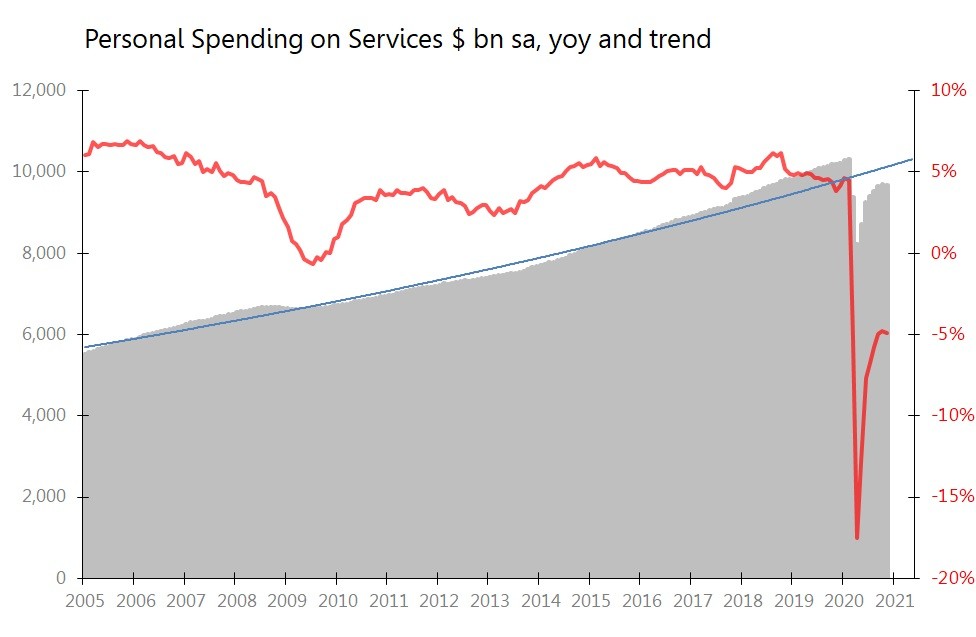

What about services? Here the case for suppressed demand is easier to make, since spending on services has not recovered to pre-covid levels: by November, personal spending on service was still down 4.9% yoy and 6% below its pre-covid peak. However, whilst it is reasonable to believe that this shortfall will be made up in 2021, this does not necessarily mean we should expect a massive rebound. After all, as the chart shows, spending on services was running significantly above long-term trend in since late 2017 until covid hit. During that period, services spending growth averaged 5% pa, whilst the long-term trend for services spending is only 3.6% a year.

If services spending merely recovers back to its long-term log trend pattern at a steady rate, it implies growth of services spending of approximately 6.2% in 12ma terms over the coming year. That's a healthy rate of growth, but only slightly faster than seen in 2018. A really powerful rebound would require spending not merely to return to trend, but to the above-trend levels seen in the immediate pre-covid years. To expect a return to trend is reasonable: but to expect a return to sharply above trend spending requires genuine faith.

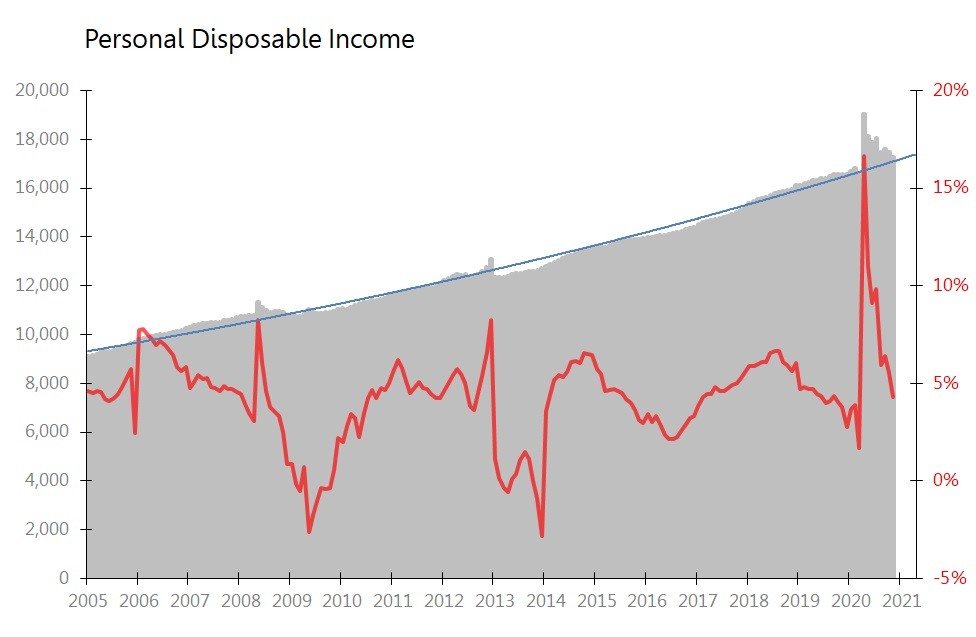

What would form a good foundation for such a faith? I would suggest that the two conditions one would normally cite would be a recovery in income growth, and a renewed surge in confidence. But once again, the evidence is less persuasive than you might think. First, the result of the government's massive transfer payments to the household sector for furlough etc is that 2020 has actually been a banner year for personal income. Despite the rise in unemployment, those transfer payments mean that by November, total personal disposable income was actually up 4.3% yoy. More than, the growth in personal disposable income in 2020 was running consistently above (log) trend.

What this means is that if personal disposable income were to return to its trend-pattern, the yoy measurements would be negative for much of 2021.

Merely to stabilize disposable income will require either a massive jump in employment, or ever-more lavish transfer payments from the government.

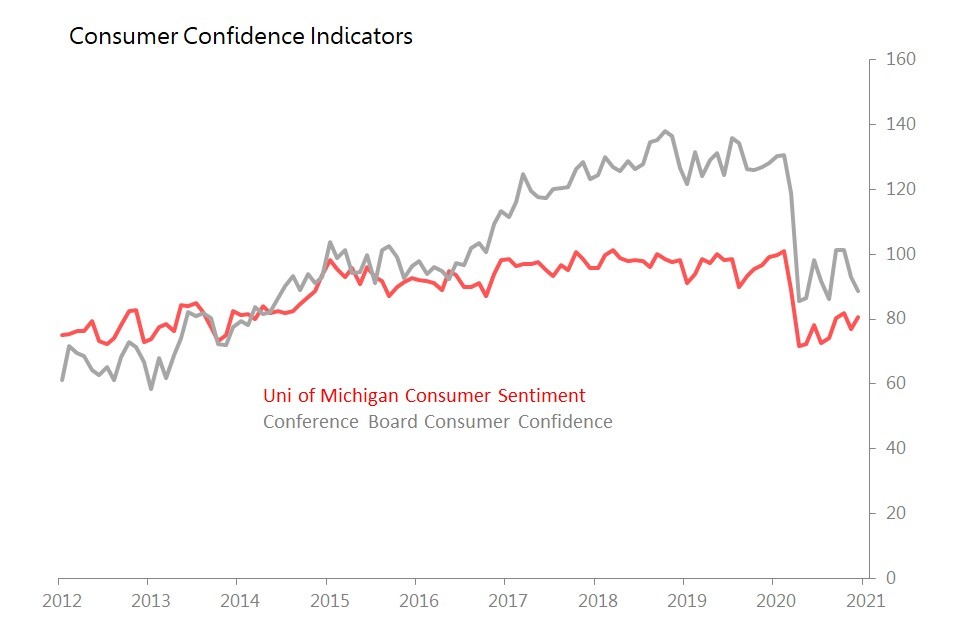

If a surge in personal disposable income seems, frankly, extremely unlikely, then the hope for a household-led rebound in post-covid spending would seem to rest on a major recovery of consumer confidence. Not only is there no sign of that yet, it was the details of the NY Fed's survey which gave rise to the 'Bleak Expectations' piece in the first place. And how plausible is it that the caution learned so painfully in 2020's pandemic will be forgotten so completely so immediately in 2021?