Dec 06•8 min read

Govt Debt Blowout - The View from the Deanery

This week the Peterson Institute for International Economics arranged a convocation of the West's most eminent economists to offer advice on fiscal policy and public sector debt to the incoming US administration. The rosta of participants could hardly be more distinguished. You'll know the names: Larry Summers, Ben Bernanke, Kenneth Rogoff, Olivier Blanchard and Jason Furman. Together they comprise what you might call the Deanery of US-consensus economics, and whilst some of them would doubtless object to being tagged 'neo-classical', they do share a heritage which combined neo-classical and Keynesian ideas.

They were being asked to give advice on US fiscal policy in the post-Covid recovery period, and to consider the implications of the steep jump in public sector debt/GDP levels the pandemic leaves in its wake. They agreed that further aggressive fiscal stimulus (ie, federal deficit spending) was required. On the more interesting question of what to do about the rise in public sector debt/GDP levels, the advice was blunt and dramatic: keep spending and don't worry about public debt levels. In fact, the key paper by Furman and Summers around which the discussion revolved had an even more dramatic message. Not only should be not worry about rising debt/GDP levels, we should recognize that, in fact, viewed in a certain way, public debt levels are historically low, indeed, unacceptably low. In that sense, not only was there room for major additions to public sector debt, the historic situation in which the US found itself made accelerating the build-up of debt almost an economic obligation.

The core of the Furman/Summers argument is that the debt/GDP measurement itself is no longer the relevant measure, but it should be replaced by various measures of the serviceability of the debt. Indeed, the debt/GDP measurement is condemned as 'backward-looking' . And in an environment of sustained very low interest rates, the net present value of US GDP is assessed at no less than $3.9 quadrillion (as opposed to the meagre $21.1trillion tallied in the national accounts). On a stock to stock basis, and discounting at very low interest rates to an 'infinite horizon GDP' means that public sector debt is revealed as stable relative to future GDP even whilst tripling since 2004 relative to present GDP. On a flow-to-flow basis, real debt service has fallen as a percentage of GDP even as debt/GDP has risen.

This is the magic of very low interest rates (it works, too, to track valuations of the S&P 500 on a fundamental basis), and it immediately raises the question of whether we can expect US rates, and thus global rate, to remain so very low over the long term. It the answer is definitely 'yes', then the Deanery's 'damn the torpedoes' attitude to public sector debt is feasible. If the answer is only 'maybe', then one has to think about those torpedoes.

So the argument that interest rates are going nowhere even in the long term, and even as public sector debt/GDP levels soar, becomes really important. And this is where it both gets very interesting, but also illustrative of the complacency of these most talented and feted men - the economists at the very apex of their profession. Their brilliance is not in doubt: but their technical expertise may have left them blind to the world in which they live, and for which they make their recommendations.

The Furman/Summers argument is an extension of an earlier paper (Rachel / Summers 2019 'On Secular Stagnation in the Industrialized World'. Its key insight is that despite enormous financial pressures which would suggest the contrary, the real natural rate of interest, hereafter r* (or r-star), has fallen dramatically and consistently. R* can be seen as the trend component of short-term real interest rates. Whilst at any one time the Federal Reserve can influence the current real rate of interest, the trend component of real rates will be driven by fundamental factors, of which the dynamics of government debt must surely be a factor.

And yet, in 2000, the 10yr forecast debt/GDP ratio in the US was just 6%, and real interest rates were 4.3%; whilst 20 years later, the debt/GDP 10yr forecast has risen to 109%, but real interest rates are now minus 0.1%.

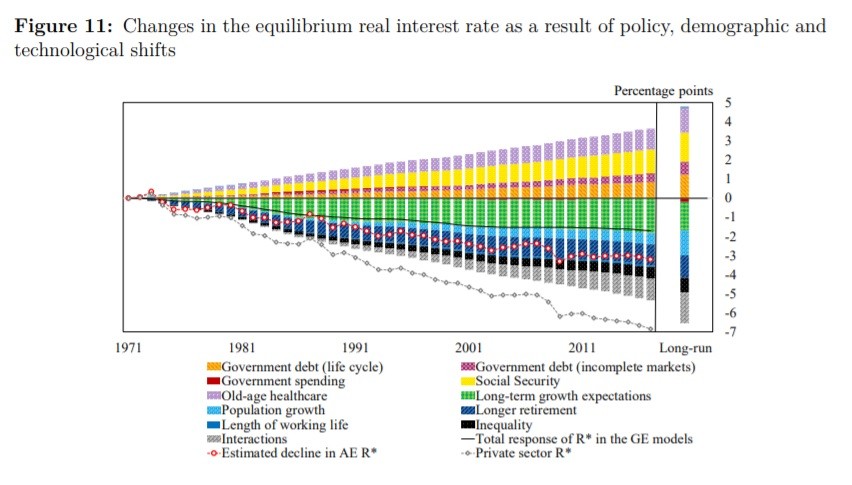

Consequently, there must be other factors besides government debt at work. The Rachel/Summers paper does a brilliant job in isolating the various measurable factors - in policy, demographics and technology - which one would expect to exert positive or negative influences on r*. It finds that the following factors must be considered to be pushing up r* consistently over the last 50 years: the size of government debt, the expansion of government spending, the cost of old-age healthcare, the cost of social security spending. Factors depressing r* include a fall in long-term growth expectations, slowing population growth, length of working life, and rising inequality.

But the key insight this work generates is that since practically all aspects of government finance have been pushing up r*, whilst actually r* has been falling, then the private sector component of r* must have been falling even more dramatically than total r*. Or, to put it more clearly, private sector investment demand is no longer big enough to absorb the flow of private sector savings. Without the impact of major government debt-raising, the excess of private sector savings would have been between 9 and 14 percentage points among advanced economies as a group.

It is at this point that, I think, the Deanery commits a crucial sin of omission. For there are two possible responses to this insight. The first is the one they take: 'since we know that the fall in private sector r* is outweighing all the factors which ought to be pushing up total r*, we can be confident that real interest rates are very unlikely to rise in a way which triggers the potential financial time-bomb of higher government debt. Not only is a higher government debt/GDP level tolerable, the fall in private sector r* makes it economically desirable, necessary even.'

But there is an alternative response which I think is more obvious, and more important. It is to ask: 'What the heck is depressing private sector r* so dramatically, against all the odds?' This is the direct equivalent of asking 'why is the private sector so loathe to invest? Why does it have to be bribed by negative interest rates to spend on real capital assets?' Or even: 'what's causing this 'secular stagnation'. Now, there is no shortage of possible reasons why the private sector is so unwilling to invest. Among the possibilities I would include:

a fundamental change in the terms of the labour / capital investment choice (aka, uber-flexibility of labour markets, the China option);

a sustained rise in labour market mobility (aka, why train my competitor's new staff?);

a rise in contingent legal and regulatory risk/costs (aka, the lawyer risk);

a rise in unacknowledged charges on profits caused by the need to 'finance' the political system (aka, corruption);

a rise in monopolistic/oligopolistic industrial structures (aka, IPR and the rise in non-tariff barriers) ;

the differential risk profile of investment in financial vs real assets (aka, buybacks, or the Boeing exemplar);

the changed source of private sector savings, in which rising corporate profits reflect dissaving in the household and government sectors.

This is surely not a complete list - you can add your own factors. What they share is that they represent possible/plausible changes in the underlying structure of the political economy of (largely) Western nations. If they are causing a problem, then I think it is part of an economists' job, part of the Deanery's responsibility, to acknowledge that and suggests remedies. The Deanery recognizes that very low interest rates bring their own problems - less scope for monetary policy responses, increased financial risk taking and hence potential financial instability, and increasingly a hobble on the effectiveness of fiscal policy responses. However, their collective response is: 'much more of the same - let's use the private sector investment strike as an opportunity to expand the government intervention in the economy'.

What sort of response is this? It is the same response which coins the phrase 'secular stagnation' to present as inevitable a phenomenon which previous generations of economists would have recognized as 'serial longstanding policy failure'. Throughout, their analysis is based on data from economies termed 'developed' and 'advanced'. Yet the belief that, for example, the UK or the US is a 'modern developed industrial economy' can only be sustained if you ignore the swathes of the economy which are very evidently 'post-modern, post-industrial, and disintegrating'. What proportion of the 'advanced' economies the Deanery explores does not share these features. It is these features which, in fact, comprise the 'secular stagnation' their analysis takes for granted.

In their defence, it can be argued that in this presentation, and in the economic papers upon which it is based, the Deanery is asked to comment specifically on government debt strategies, and that to go further is to tread upon political ground. (The same may be said about this comment.) True enough. But what sort of economics is it that has no interest in the impact of the structure of the political economy on investment, savings, growth, interest rates, employment etc? The Deanery, for all its brilliance, is not exactly complacent; but it is strangely selective in its concerns.