Sep 08•4 min read

The Valuation Project - Part 4, Germany

The first part of this project suggested a methodology from first principles for valuating stockmarkets which aimed to meet two criteria:

First, that the first principle assumptions seem reasonable: ie, that there is a reason why they ought to work;

Second, that in practice, that the valuations produced by the methodology have reasonably tracked the actual valuations of stockmarkets over a long period of time.

The principle which I believe to be reasonable is that the price (value) of an asset should be such that it maintains its position in the economy over time. If it loses its position over time, then we can assume that the asset was overpriced: if it improves its position over time, we can assume that it is underpriced. In practice, this implies that the price/earnings multiple of the asset should be tightly linked to the long-term experienced nominal growth of the economy, adjusted for volatility in that growth. I took the long-term to be a 10yr period. In addition, I used the Kalecki equations to generate a track record of profits, for the 'earnings' part of the valuation.

This approach reasonably satisfied both criteria for the US and the S&P500.

For the UK, it failed for the FTSE100, but reasonably succeeded if that index was conceived as a global index rather than a specifically UK index, and therefore subject to the valuation framework of the US. For the more UK-centric FTSE250, the methodology worked reasonably well.

For Japan, it implied a dramatic and persistent over-valuation of the TOPIX index. The emergence of the dramatic undervaluation since 2013 was co-terminous with the large-scale buying of index EFTs by Bank of Japan, offering the working hypothesis that BOJ's buying is sustaining otherwise unjustified over-valuation of the market.

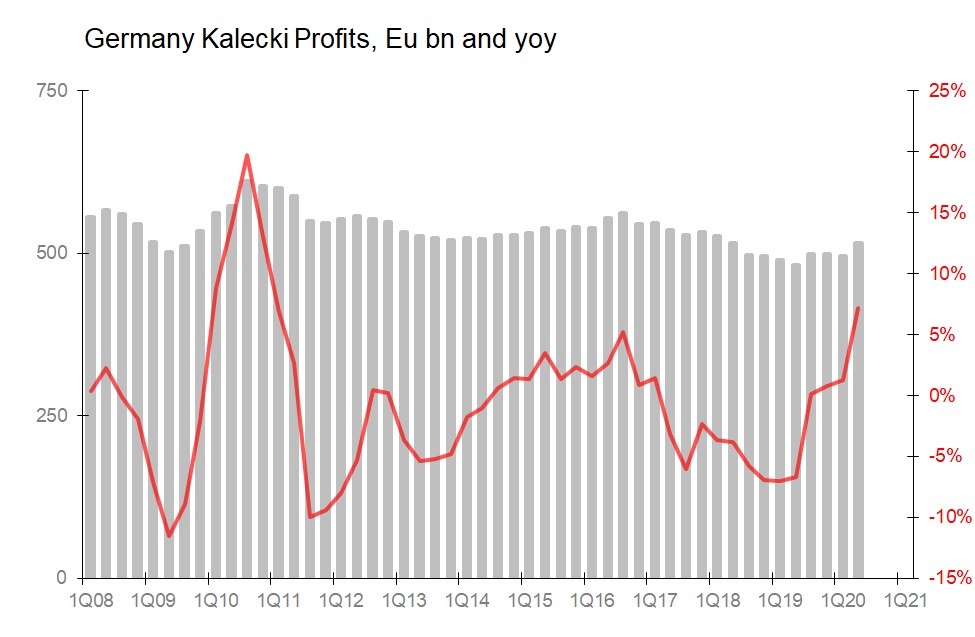

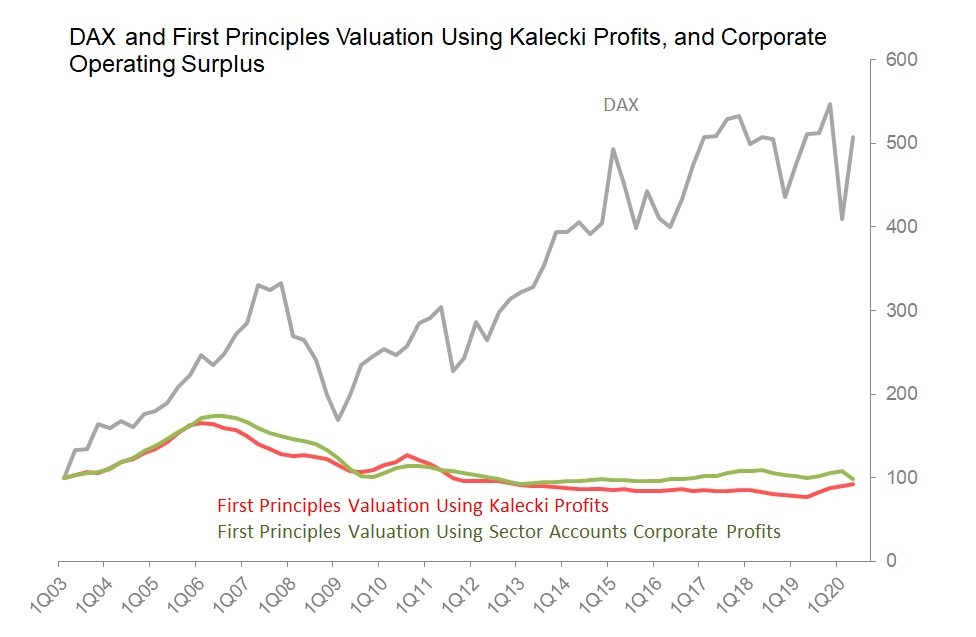

This piece applies the same methodology to Germany and its DAX stockmarket index. The Kalecki profits track record is uninspiring, with profits largely stagnant or slightly sagging over the previous decade. However, the DAX index has soared.

The result, even given the relatively pedestrian long-term rate of nominal GDP growth (running at 3.5% in the 10yrs to end-2019) is a dramatic over-valuation of the index. In the 10yrs to end-2019, Germany's nominal GDP has risen 41%, Kalecki profits have fallen 6.5%, and the DAX has risen 122.4%. This result suggests either that the profits estimated by the Kalecki equations are wrong by several factors, or that there is something else going on which generates and sustains this overvaluation.

But the Kalecki profits results are not the problem: the corporate profits shown in Germany's official quarterly sector accounts have a slightly more boyuant trend than Kalecki suggests, but the difference is not big enough to make a material difference to the conclusion. If the DAX was thought to be properly valuing assets at the start of 2003, then the overvaluation by 2Q20 was running either at 5.51x using Kalecki profits, or 5.14x for the sector accounts profits. In either case, the overvaluation is very pronounced.

We must then wonder about the starting point: perhaps in 2003, the DAX was simply dramatically undervalued, and has subsequently risen to a more stable valuation. One cannot be dogmatic about the point at which the DAX was showing a fair valuation, but one can say that between 2003 and 2009, the divergence was generally quite limited, with little difference in valuation at the beginning and the end of that period; but that since around 2009 until the end of last year, the overvaluation multiple expanded dramatically.

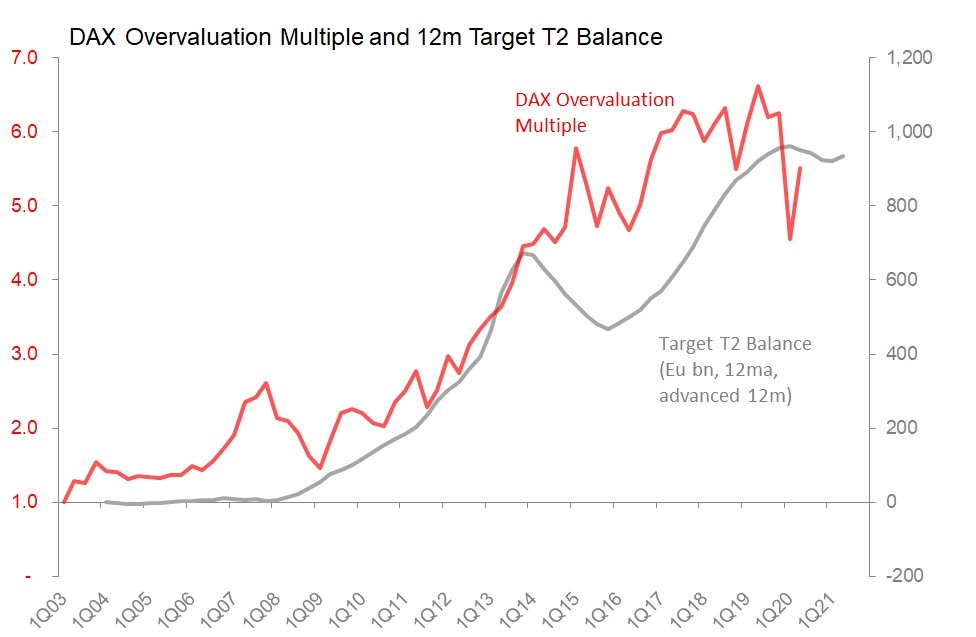

We are, then seeking a reason - and specifically a change in cashflows in Germany's financial system - which could account for the explosion of overvaluation in Germany's stockmarket since around 2009/2010. And the obvious tell-tale sign is found in the Bundesbank's Target 2 position with the European Central Bank, because it is this figure which proxies changes in the German banking systems domestic net clearing balance. When the Bundesbank's Target 2 lending to the ECB expands, it is doing so because of the net inflow of cash into its financial system, principally from other Eurozone banking systems deemed less safe than Germany's. This is, effectively, a cashflow inflow which has no immediately matching demand on the production or services of Germany's domestic economy. Given that Target 2 totals track this 'surplus' cash, it is not surprising that since it started rising dramatically in 2009/2010, that rise has foreshadowed the expansion of the DAX's overvaluation multiple.