Apr 08•11 min read

Our Times: Where It Went Wrong

Even before coronavirus put our institutions, finances and mental picture of how the world works under pressure, a series of 'unexpected' political developments in the West adverted to a widespread discontent with how globalized capitalism was working. Those 'unexpected' developments surely include the collapse of Western financial institutions in 2008/09, the withdrawal of consent by the British demos for continued membership of the EU, and the election of the US's first reality-TV/social media president. But in truth, the 'unexpected' political developments embrace a far wider spectrum of discontent, and include a new generational purported embrace of 'socialism' in Europe and the US, which seems linked to the emergence of a distinct hyper-urban political sensibility which (to me) seems quite determined to put dramatic cultural distance between it and the rest of the world.

It seems obvious to me that this discontent is also a reflection of a multivariant series of fractures in economic relations. A rise in 'inequality' is an all-embracing phrase which actually captures a series of fractures: between young and old; between property owners and those for whom property ownership no longer seems a feasible goal; between household income demographics in which identifiable regions no longer aggregate to a 'coherent sample'; between those with stable employment, and the penumbra of the 'precariat' which includes both those in the 'gig economy', those quietly and energetically working the gaps in the immigration system, and the self employed. And, of course, good old fashioned income inequality.

The bad news is that we can find the drivers of almost all these discontents embedded in the very foundations of the free market capitalism most of us wish to preserve. The good news is that this structure, though demonstrable and shared by both the US and UK, is historically abberrant. There is nothing 'inevitable' about it. It is capitalism, Jim, but not as we know it.

The promise of free market capitalism is simple: it works. The Invisible Hand magically arranges an enriching outcome for society by organizing the 'selfish' behaviour of profit-maximising entrepreneurs and consumers to beneficial ends. And because it delivers the goods, we are rational in our tolerance of the inequalities and price differentials which are built into the machine as the necessary incentive structures. It works.

What is more, it was possible to go into some detail about the mechanisms involved. Typically, this would involve capital markets (of various descriptions) mobilizing the savings of the household sector (including the savings of the very rich) into productive investment. That investment would not only increase profits for the investor, but would also raise the productivity of the nation, and consequently the real income of the workers. And as household income rose, so too would the savings they made, and consequently the investment. It works.

This model of beneficient saving and investment is, I think, with various modifications, the one we all have in the back of our minds as the way capitalism works. It is part of our intellectual inheritance.

It is not, however, a picture of our current capitalism. In fact, it is dramatically, and fatally, wrong. Happily, this is not an opinion, it is measurable and demonstrable. And the fact of the error, and the causes of it, are what ties together almost all of our current discontents.

The diagnostic clue is present in the key driver of free market capitalism: profit. On a macroeconomic scale, you can calculate profits for the whole economy by looking at it as the residual 'saving' in an economy when all other aspects of saving / dissaving have been x'd out. This is the key insight unearthed by the Polish economist Michal Kalecki, and it forms the basis of efforts to calculate profits by such institutions as the US's Bureau of Economic Analysis.

Crucially, Kalecki's insights not only allows us to calculate (or more honestly, estimate) corporate profits, but also disaggregate the sources of profit - ie, those patterns of spending and saving which allow/generate profits to be earned. These are i) net investment; ii) saving/dissaving of households; iii) saving/dissaving of government and iv) the position with the rest of the world (ie, is the rest of world saving or dissaving in their commercial contracts with you. These metrics are exhaustive - there's nothing more that you need to know or estimate in order to understand profits growth.

The traditional capitalist expectation is that the household sector saves out of income, and the corporate sector invests those savings profitably - and so we get rich. However, in the US (and UK), that pattern has been reversed: the household sector dissaves, and it is that dissaving which props up corporate profits.

This is not a hypothesis, it is a measurement. Here's how the breakdown of the source of US corporate profits looks: in the 12m to Dec 2019, household dissaving accounted for 57% of profits, net investment 35%, government dissaving 18% and net exports (ie, dissaving with the rest of the world) stripped away an amount equivalent to 10%.

Now I'd have thought it obvious that if corporate profits were dependent on the household sector taking on debt to buy your products/services, this is an obvious source of instability. (Even if you have a central bank absolutely determined to keep the balls all up in the air). Another source of instability would, of course, be for corporate profits to be dependent on the government dissaving (ie, the fiscal deficit causing a rise in national debt).

By contrast, if corporate profits are dependent on net investment and a surplus with the rest of the world, you're probably not having the same potential for instability.

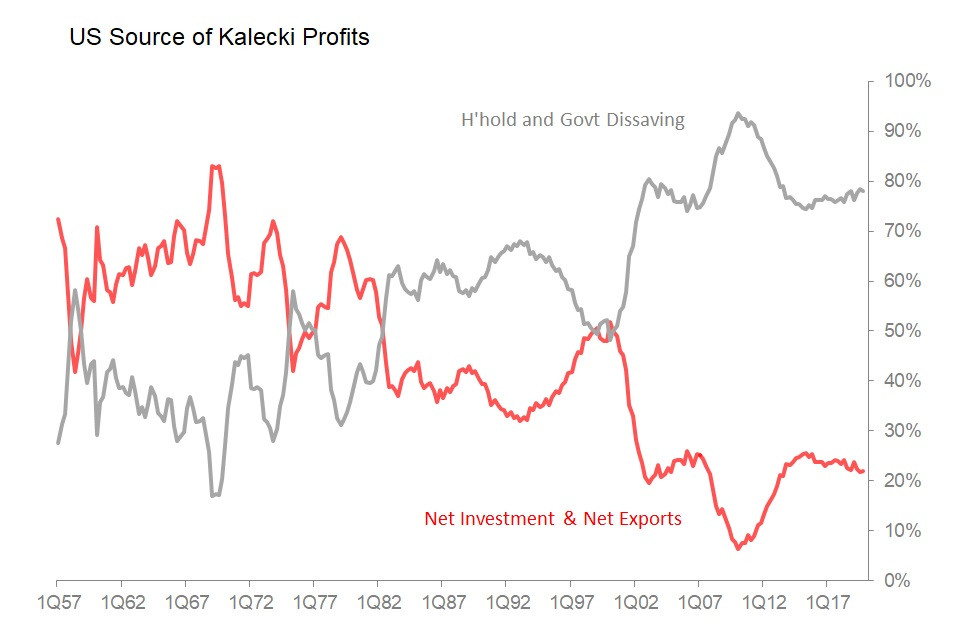

So let's measure the household sector & govt dissaving proportion vs the net investment, net exports source.

Here's how the US looks:

This is a remarkable picture: since the early 1980s, US corporate profits have been more dependent on sustained dissaving from the household and government than on net investment and net exports. During the last 20 years, that dependence on the household and government being prepared to spend more than it earns has become extreme.

And here's how the UK looks: a very similar, if slightly less extreme, change in trajectory around the late 1970s / early 1980s.

In both economies, if the household sector ever decided it would curb its spending to keep it more in line with the salary and wages it earns, and if the government ever decided to get serious about no longer running deficits, corporate profits would collapse. And with the collapse in corporate profits would come a fall in financial asset prices, which in turn would further depress household's willingness to spend more than they earn. The plates can be kept spinning only at the cost of the sustained beggary of households and the state.

For how does the household sector manage to dissave quite so dramatically and consistently? There are three mechanisms: they take on more debt; they raise money from the sale of real assets (or by refinancing them); and the rise in financial asset prices bring with it a rise in income from assets relative to wages (personal income from assets rose from c10% in 1950 to a peak of over 35% in the mid-1980s and is currently around 31- 32%). Among other things, this increased reliance on financial asset income re-emphasises the importance policymakers have increasingly laid on maintaining 'financial stability'. The world's central banks are riding the tiger.

Now, whilst I do not know if there is an ideal split between sources of profits, it seems obvious that if profits growth depends on the household sector and the government sector dissaving, then the corollary must necessarily be higher stocks of household and government debt.

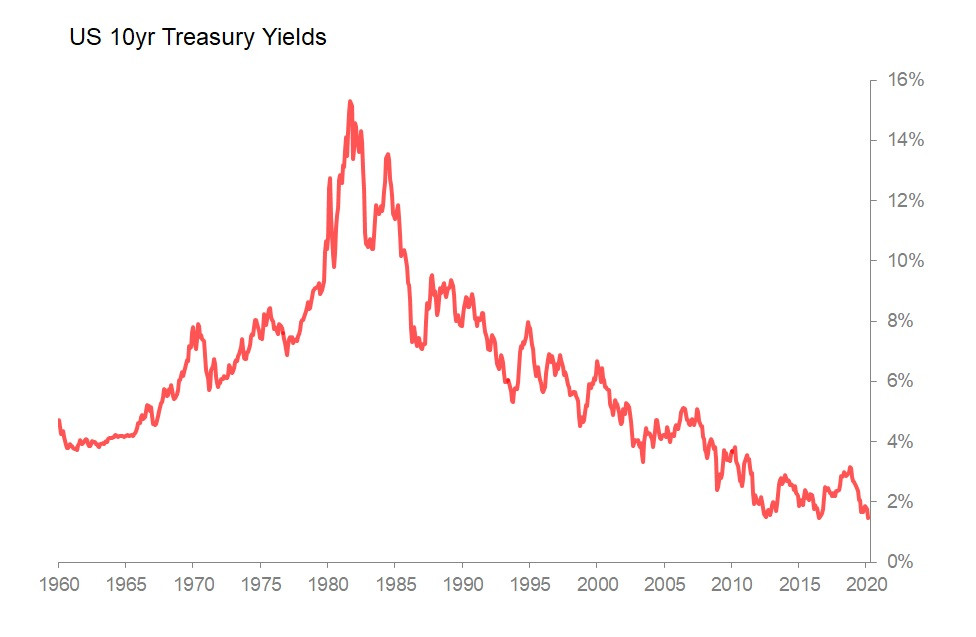

It is also obvious that this then puts a premium on central banks' maintaining 'financial stability' through supporting equity prices and, by extension, housing prices, since to do otherwise would be to undermine the willingness of the household sector to dissave continually. This, then, is also the essential background to the political decision to lower interest rates essentially to zero.

It is now obvious what the downsides to this are: rising household financial instability through higher debt loads, increasing unaffordability of housing, and, through a lack of corporate investment, slow productivity growth and hence slow, or negligible, growth in real earnings.

This is the bad news. The good news is that the situation as we have lived it is not 'inevitable' - indeed, historically it is abberrant. Prior to the early 1980s, corporate profits in both the US and the UK were much less a function of household and the state deficits, but rather the impact of net investment and net exports.

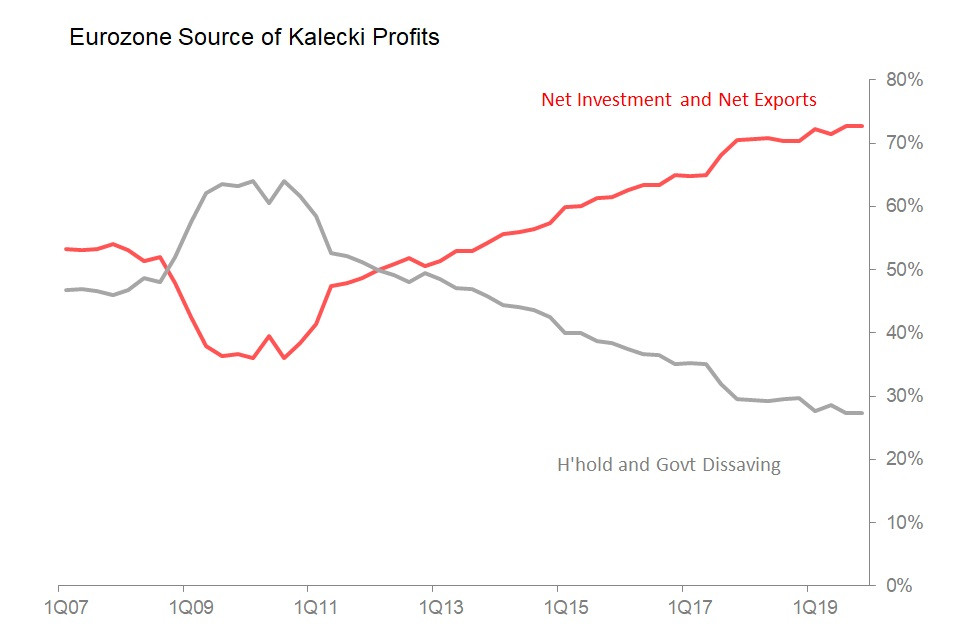

Currently in the Eurozone, the source of corporate profits is the mirror image of what has happened in the US and UK, with more than 70% of profits attributable to net investment and net exports, and less tha 30% coming from household and government dissaving. I am not arguing that the Eurozone's profits structure is perfect - indeed, in its current extremity it looks just as abberrant as what has happened in the US and UK.

Rather, the message to be taken from earlier experience in the US and UK, and now from the Eurozone, is that a different 'model' of free market enterprise is not only possible, but it is both 'normal' and preferable.

Keynes once asked rhethorically why we tolerate wide inequailities of income? His response was 'because it works' - because by allowing the owners of capital to get rich, the invisible hand works to make us all rich. In fact, he went further: since the rich cannot possibly consume their wealth, it must inevitably be invested back into the real assets which drive growth. In the deformation of capitalism with which we have grown up, this simply is no longer obviously true (why invest in real assets, when the Federal Reserve is guaranteeing a good return on corporate buybacks?) In fact, it would seem quite the opposite: the sustained rise in corporate profitability which allegedly justify the rise in inequality is predicated precisely on the customers' long-term beggary. Meanwhile, the historic justification of public equity markets as being to raise risk capital for real investment, has also dwindled.

At the beginning of this article I argued that worries about 'inequality' referred to a series of dramatic fractures in our political economy which went far beyond income inequalities, serious though those are. I believe that this distorted structure of profit attribution is absolutely the root of those problems.

So why do we tolerate it? Those of us who would defend capitalism should recognize that what I have described is not a problem, it is the problem.

At this point it might be asked whether what I'm doing here is identifying a causal relationship between profits and our discontents, rather than merely describing what is actually happening. But the answer is surely 'both': economic decisions both fiscal and monetary in part react to the situation encountered, but in turn also help to shape them - that is, after all, the point. And if you read the history of the FOMC meetings as laid out in the publicly-available transcripts, there is no doubt at all that interest rate decisions have (increasingly) been taken in response to stockmarket volatility.

But this also leads to a cheerful conclusion: the situation we have in the US and UK is neither inevitable, nor 'natural', nor immutable. It is quite possible to imagine policies which seek to alter the patterns of household savings/spending, corporate net investment, and government fiscal balances. In other words, it is quite possible to imagine policies which step back from this rentier-style model of capitalism to one which restores a model which rewards growth in investment spending and (by extension) productivity whilst discouraging net dissaving from the household and government sectors.

Which returns us, actually, to the impact of the coronavirus. If nothing else, the global pandemic has made it impossible to ignore the choices we have made in the eternal policy trilemma identified by Turkish academic Erda Gerck between efficiency, sustainability and equity. The message of our times is that we have paid dearly in sustainability and equity for our pursuit of efficiency. Coronavirus made that impossible to ignore, but the evidence is there, right in the circumstances demanded for profit growth.