Apr 28•5 min read

Covid Case Notes China: The Maths of the Aftermath

Inadequate and untrustworthy as its data may be, China is so far the only set of signals we have for what happens in the immediate aftermath of the first struggle with Covid-19. What hints, if any, can we pick up?

The impact on GDP is the starting point: 1Q GDP fell 6.8% yoy in real terms, cutting the 12ma to 3.2%. If what happens next is only the resumption of normal patterns of economic activity - ie, unless there is a dramatic post-Covid rebound in spending, output and trading patterns - then this lays the foundations for an absolute contraction in 2020 GDP growth. Even with a gradual recouping of lost activity emerging gradually over the rest of the year, China's real GDP is likely to contract during 2020 (by up to 2% yoy).

Whilst March data has been taken to show a rebound of sorts already underway, that 'recovery' is so far much too mild to avoid an outright contraction in 2020. The most leading indicators we have are March's PMIs, both the official results from the CFLP, and the Markit-conducted ones from Caixin. On the face of it, these look encouraging: for the CFLP, manufacturing rose to 50.9 after falling to 31.8 in February, and services recovered to 52.3 from 29.6. Expansion! Caixin's results were similar, with manufacturing recovering to 50.1 from 40.3, and services rising to 43 from 26.5.

But these are essentially diffusion indexes (ie, the net of 'expanding' minus 'contracting' during the month, so a recovery even into the mid-50s in March signals no recovery to pre-Covid levels if Feb's results were in the 20s and 30s. If a net 20% of firms reported contraction in February and a net 2.3% of firms reported expanion in March, there is still an enormous amount of ground to regain.

Bear this in mind in reading PMIs, particularly in Europe, over the coming months.

Now let's look at what happened to nominal GDP. It fell 5.3% yoy in 1Q, cutting the 12m to +5.5%. Much the same maths which applies to real GDP applies to nominal GDP - it will be surprising if China's 2020 nominal GDP is larger than that of 2019. Where was the damage done? First, China's trade surplus almost disappeared, falling by 83% yoy to only Rmb89.4bn in 1Q. This fall accounted for 37% of the yoy fall in nominal GDP.

Excluding the impact of the trade surplus, nominal domestic demand shrank by 3.4% yoy - perhaps a surprisingly modest fall. 1Q domestic demand is affected by the Lunar New Year holidays, and usually falls by about 13% qoq in nominal terms: this year it fell by 25.7% qoq.

I do not know yet know exactly what happened to the fiscal position in 1Q. The extrapolation that historic trends in revenues and spending merely continued must surely paint a picture of greater fiscal conservatism than actually happened. However, even this conservative extrapolation suggests a sharp widening of the fiscal deficit. And by extension, that suggests a sharper fall in private domestic demand, of approximately 8% yoy in 1Q. If the fiscal deterioration accelerated in 1Q, then that fall in private domestic demand will have been sharper.

So, to summarise: the fall in the trade surplus accounted for approximately a third of the overall fall in nominal yoy GDP, with falling domestic demand doing the rest of the damage. Very probably, that fall was muted by an expanding fiscal deficit, with non-state demand suffering a very sharp fall.

This worse-than-it-seems hit to non-state demand is also supported by income and spending data for 1Q. This shows that per capita disposable income rose only 0.8% yoy in 1Q (vs 9.1% in 4Q19), but that per capita spending fell by 8.2% yoy (vs +9.4% in 4Q19). In other words, the household sector reacted to the economic disaster of Covid-19 by raising its saving rate (or, more accurately, moderating its dissaving). This in turn will have had the result of depressing nominal private demand. A fall of 8% yoy in nominal private domestic demand looks . . . realistic.

One Chinese response to the emergency at least is shared by the rest of the world: the credit taps were turned on. On the widest measure, aggregate financing rose 11.5% yoy in March, with an additional Rmb5.06tr added, which was a monthly movt 2.4SDs above historic seasonal trends. The slightly less inclusive measure of domestic credit rose 12.2% yoy in March, with a rise of Rmb5.921tr, which reflected a monthly movt 1.5SDs above historic seasonal trends.

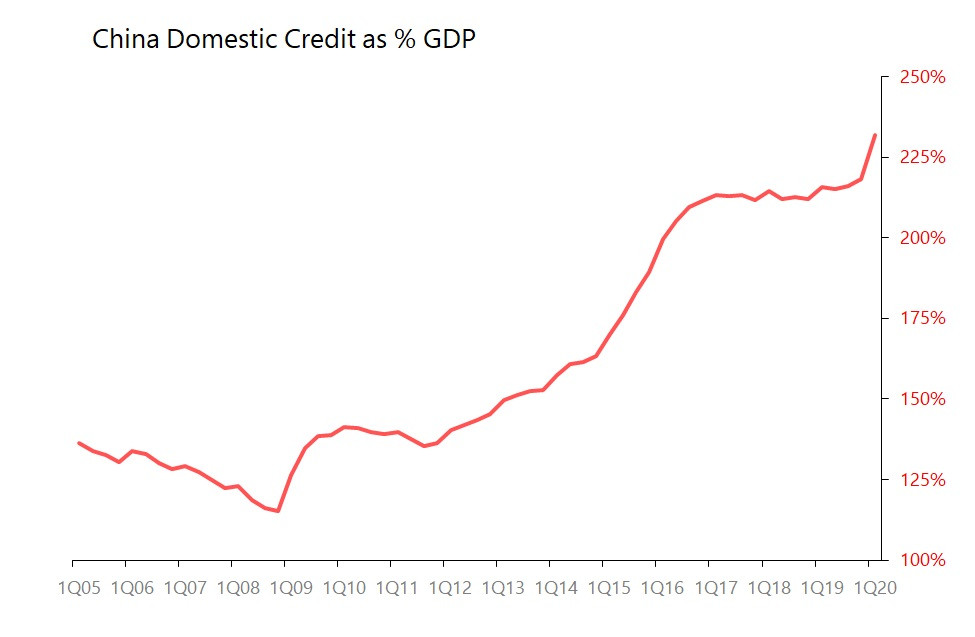

At least two things follow from this. First, China's debt/GDP ratios have spiked up sharply, with domestic credit/GDP rising to 232% at end-1Q from 218% in end 4Q. It seems unlikely that nominal GDP will rise at all this year, let alone by the 11-12% gains showing in aggregate financing and domestic credit, so the rise in China's debt/GDP levels is not a 'one-off', nor is its full extent yet visible.

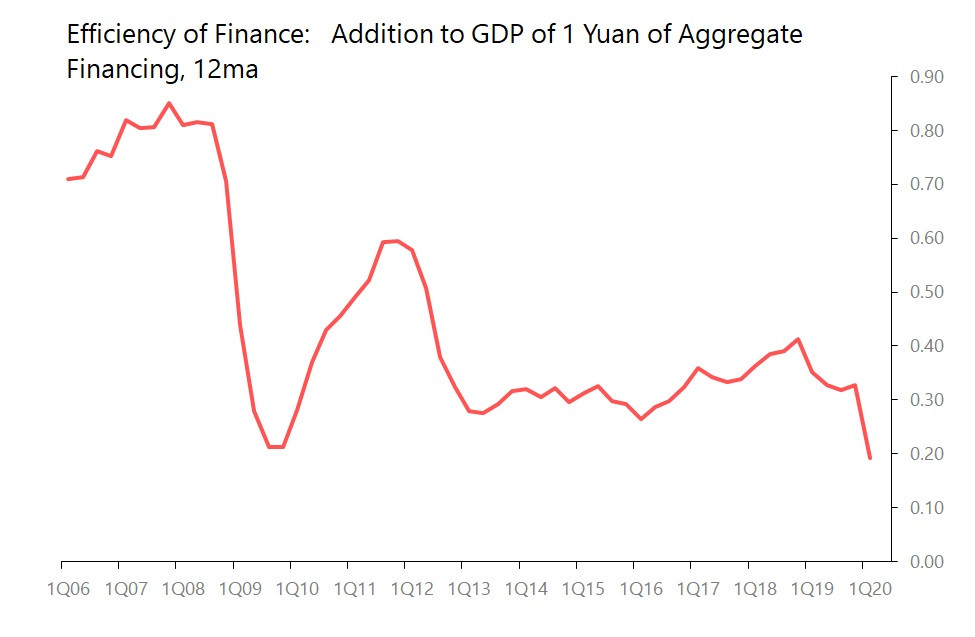

Second, the crisis has undone at a stroke all the work of the last decade to improve the marginal efficiency of finance. In the 12m to March 2020, the addition of Rmb100 of aggregate finance has been associated with only Rmb 19 of additional nominal GDP. This is a new record low, and will surely sink further during the coming year.

The bottom line is grim indeed: China's debt-based structure of economic growth was and is extremely vulnerable to the immediate economic consequence of Covid-19. The damage done is not yet obvious, but will continue to be revealed even as China 'recovers'.

We should expect similarly debt-fuelled economies to face much the same extended financial stress.