Feb 29•8 min read

Ill Seen, Ill Said

The predicament is unprecedented in my experience. The best I can do is tell you honestly what I believe.

First, almost all of the economic data currently being released is irrelevant, since almost all of it records how the economic situation was developing before the coronavirus took hold. So fast has the virus, and the fear of it, spread, that the recent past is a different world. Consider: among the data I tracked last week were 19 confidence surveys - usually among the more timely of the data which emerges. Of those, six surprised on the upside, only five disappointed on the downside (mainly in Asia) and eight arrived roughly where expected. To summarise: last week's confidence data was modestly positive, as it has been almost consistently since September.

And here I will single out the State Street Global Investor Confidence indicator for a special mention: it reported global confidence up 2.5pts to 77.9, bolstered mainly by a 5.4pt rise in European investor confidence to 111.1, but also by a 2.4pt rise to 68.6 in the US, which offset an 11.9pt decline in Asia-Pacific to 83.6. (I do not mean to malign State Street's efforts. It's indexes merely illustrate the depth of the data-problem).

Only today (Saturday) are the first real signs of the economic damage being done beginning to shine on our screens. China has reported its official PMIs for February's manufacturing and non-manufacturing. The CFLP manufacturing PMI dropped 14.3pts to 35.7, the worst drop I've seen from any country ever. But the CFLP non-manufacturing PMI was worse: it fell 24.5pts to 29.6. I can find no mitigation in any of the details. Rather, those details paint a picture of China's economy overwhelmed and staggering. Lord alone knows how we will start counting the fiscal and financial cost, or how dealing with those costs will shape or distort China's economic recovery.

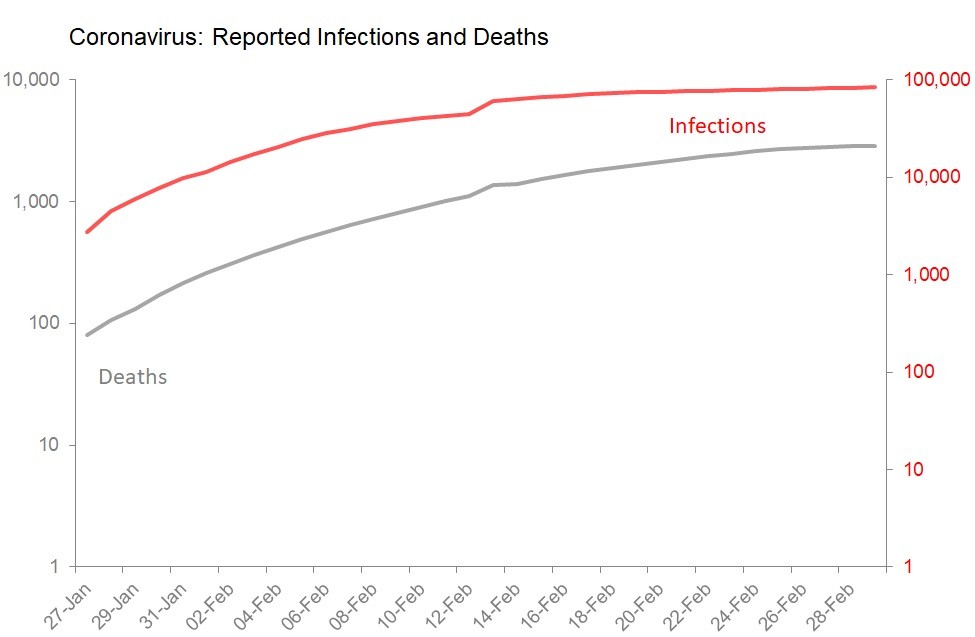

Second, the current medical data we have is not consistent with current fears, but those fears feel very reasonable nonetheless. Globally, the rise in confirmed infections has not remained exponential, as it would need to do were it to spread to millions or tens of millions in the near future. Rather, its progress has slowed dramatically. China's willingness to shut down its economy appears to have at least slowed the virus's rampage, and other places (such as Singapore) appear also to have discovered a way to constrain its ability to spread.

To set against that, the 7-day death rate is now significantly higher than the 'around 2%' recently adopted as a consensus: in the last seven days, the death rate is up to 3.4%. On the other hand, the 7-day recovery rate stands at 43.8%, and the number of unresolved cases (neither recovered nor dead) is now falling - today (Saturday) there are 44,180 unresolved cases, which is down 24.4% from the peak of 18 February.

This would be more comforting were it not for likely massive gaps in the data. With the best will in the world, China has a political system which is profoundly unfriendly to whistle-blowers at all levels of administration. We cannot believe that even the mortal importance of China 'getting it right' in the current situation will necessarily overcome the obstacles to true discovery. Perhaps more importantly, the almost complete absence of reported cases in India, Indonesia and much of Africa is utterly implausible. Very populous countries with relatively poor infrastructure and relatively meagre administrative capacity are precisely the places one would expect the virus to find a friendly reception.

In short, I cannot buy the comfort offered by the chart.

Third, if size were the only thing that mattered in determining the impact of the disease, then Italy (population 60.4mn, 888 confirmed infected, 21 dead as of 28th February) doesn't matter very much compared to China, India, Indonesia etc. But Italy matters because the virus has landed on one of the most vulnerable parts of the world economy. Containing the virus, or dramatically slowing its progress (which I think is the best we can legitimately hope for) will demand a degree of political and administrative capacity which Italy may not have. That political and administrative capacity is, in any case, curtailed by EU structures which are slow and partial because of unavoidable multinational conflicts of interest.

And Italy matters also because as things stand it has both very restricted fiscal and financial capacity to roll with the punches the virus is going to throw at it. Its membership of the Eurozone is not the only reason for that, but the Eurozone's constraints certainly amplify the risks, even as they also conceal them. (For example, does Italy have the sovereign right to manage its own sovereign debt? If not, who does? Does Italy have the autonomy or the capacity to rescue its financial system if it needs to do so?) For the very same reasons, Italy's fiscal and financial fragility is also very likely to be contagious.

So we need to look at that fiscal and financial fragility. The underlying problem is well known: Italy's public debt stands at 137.3% of GDP, and with nominal GDP growth averaging only 0.8% yoy during the last decade, attempts to bring that ratio seem unlikely to have more success in the future than they have in the past. This is despite the fact that on many measurements, Italy's attempts to pursue a more fiscally and financially conservative set of policies have been a success, insofar as they have moderated the risk associated with Italian financial assets.

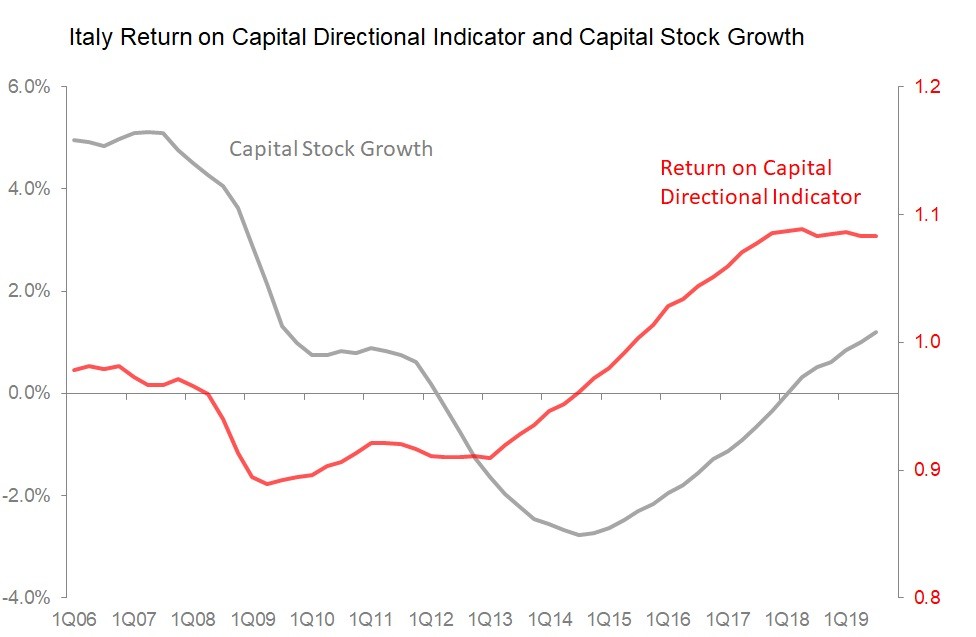

Unfortunately, those same attempts have had the side-effect of lowering Italy's potential growth rate over the medium to long term. For example, private sector deleveraging efforts have curtailed private investment spending, which in turn has pushed up Italy's return on capital directional indicator. But this has been achieved at the cost of leaving its 3Q19 stock of capital 8.3% lower than it was in 2011. This fall in capital stock in turn constrains productivity gains, which helps explain why by 2018, per capita GDP was 11.7% below its peak of 2006.

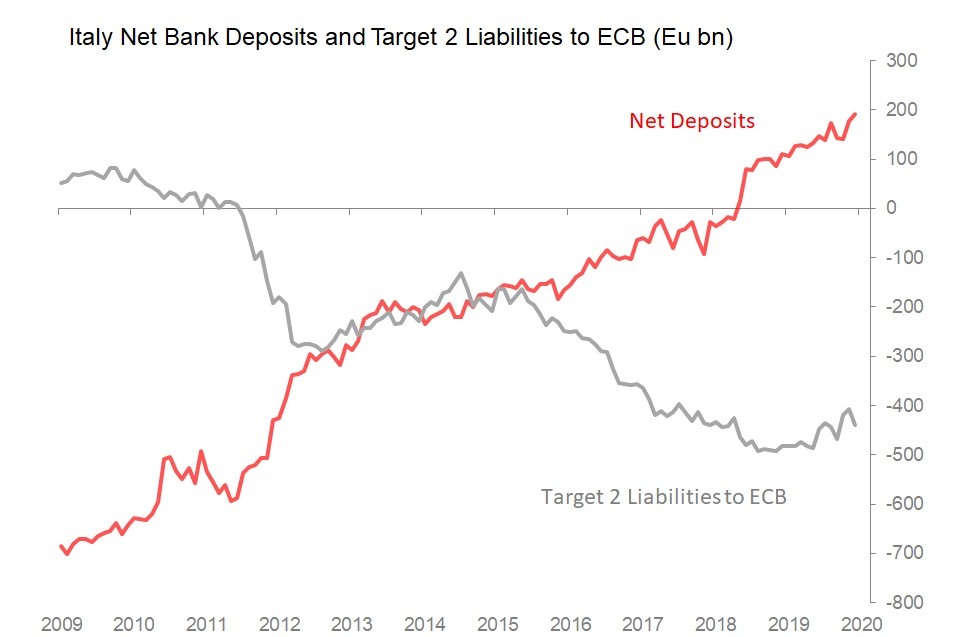

Meanwhile, Italy's banking system has spent the last decade attempting to deleverage both its own domestic operations and, latterly, also its outstanding liabilities to the ECB. And it has been quite successful in this, particularly over the last two years. The domestic story starts with the fall in the banking system's loan/deposit ratio, which just before the financial crisis hit stood at c140%. Since then it has steadily to stand at around 92% at the end-2019. The banks' customers went from a net credit position of just under Eu700bn in 2009 to a net deposit of Eu192bn at end-2019.

This pain involved in this domestic deleveraging has been dulled by an increase in the banking system's net debts to the rest of the Eurozone banking system expressed in the Target 2 balance with the Eurosystem (ECB). In 2009, Italy had a net positive Target 2 balance of around Eu50bn, but this turned into a net liability to the system in 2011, and this liability grew to a peak of around Eu490bn in early 2018, before moderating to end 2019 at a liability of Eu439bn. As the chart shows, there have been times (most obviously in 2011, but then again, modestly during 2015-2017) when the inflow of cash represented by a rise in Target 2 liabilities facilitated an improvement in the net domestic deposit position. However, in the last two years, the sustained deleveraging achieved looks to have been achieved wholly by domestic efforts - ie, this looks like a genuine sustained financial recovery.

However, it is precisely this improvement which will be reversed, possibly dramatically, by the impact of coronavirus. It will do this most obviously by short term capital outflows, but in the longer term by undermining corporate profitability and private sector cashflows. We will not learn of the broad impact on Italy's corporate sector for another six weeks, but we can be fairly certain of the negative impact on Italy's current account. During 2019 Italy reported a current account surplus of Eu53.35bn, which included a Eu17bn surplus in travel revenues generated by Eu44.5bn in tourism revenues earned by Italy minus Eu27.5bn in tourism abroad. That Eu17bn in net tourism revenue will be a casualty of the coronavirus.

More generally, the contours seem inevitably to be a recession which will bring at the same time immediate fiscal pressures on the current fiscal deficit whilst also ratcheting higher the current public sector debt/GDP ratio. The improvements in Italy's financial risk profile so painfully achieved will thus be reversed.

Worse, the combination of unexpected fiscal and financial challenges will not only sour Italy's long-term prospects in the Eurozone even further, but will also generate a formidable challenge to Eurozone fiscal and financial rules.

It is said that disease discovers the weakest victims. Within the Eurozone, it has found Italy.