Nov 22•4 min read

The Vulnerabilities of Germany's Escape from Recession

Germany released the detailed breakdown of its 3Q GDP, giving us the opportunity to judge whether its narrow escape from technical recession (down 0.2% qoq in 2Q followed by +0.1% in 3Q) looks sustainable.

What do we find? First, in nominal terms yoy GDP growth accelerated to 3.1% in 3Q from 2.1% in 2Q19 and 1.1% in 3Q18. The bad news is that this acceleration is almost wholly owing to a low base of comparison in 3Q18, a tailwind which reverses sharply in 4Q. In the absence of a genuine improvement in underlying momentum, the yoy comparison will sink back to around 2.2% in 4Q19. However, when it comes to final spending on domestic product (ie, GDP ex-inventory changes), the news is better, since 3Q19 saw a mild inventory fall, whilst 3Q18 saw a sizeable income build. As a result, final spending on domestic product rose no less than 5% yoy, which was the sharpest rise since 2Q16, and included a recovery of underlying momentum which almost fully reversed the momentum lost in the previous quarter.

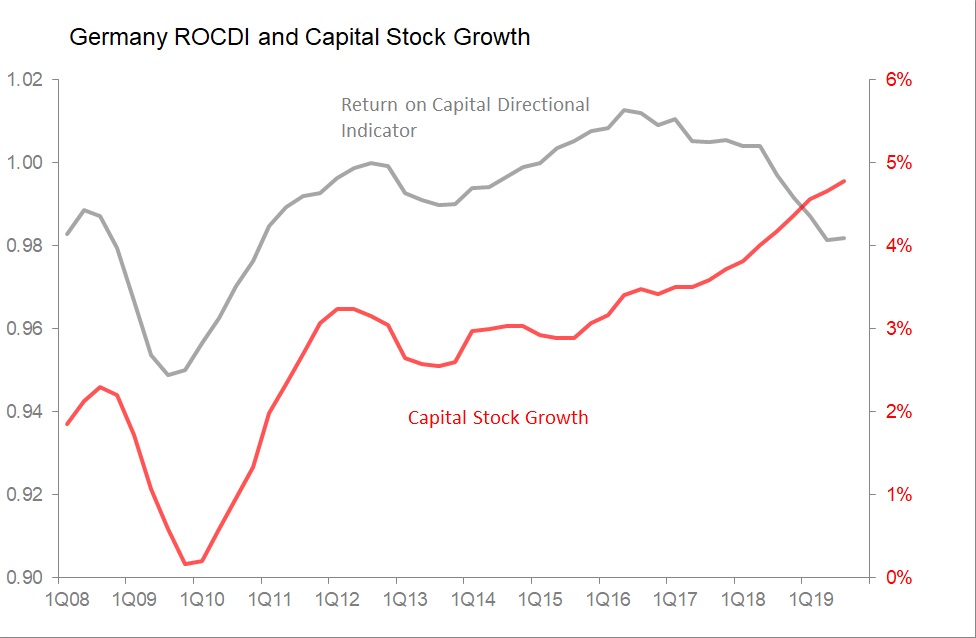

Final spending on domestic product is the numerator used in my Return on Capital Directional Indicator (ROCDI), and the 3Q boost was just enough to allow it to stabilize the steep fall in ROCDI seen since the beginning of 2018.

That, however, is probably where the good news stops. For absent any dramatic de-stocking in 4Q, the continuation of current trends in investment and in nominal GDP growth will result in the ROCDI resuming the sharp fall it has seen since 2018.

Not only is the 3Q stabilization in ROCDI hostage to Germany's inventory behaviour, but we can also observe that:

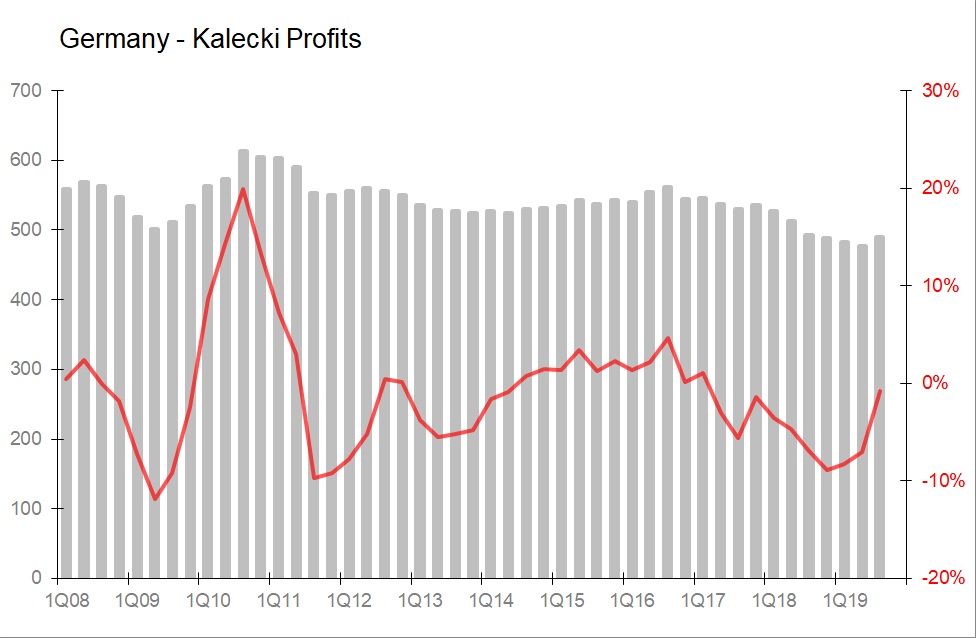

the fall in overall profits has not yet been convincingly reversed;

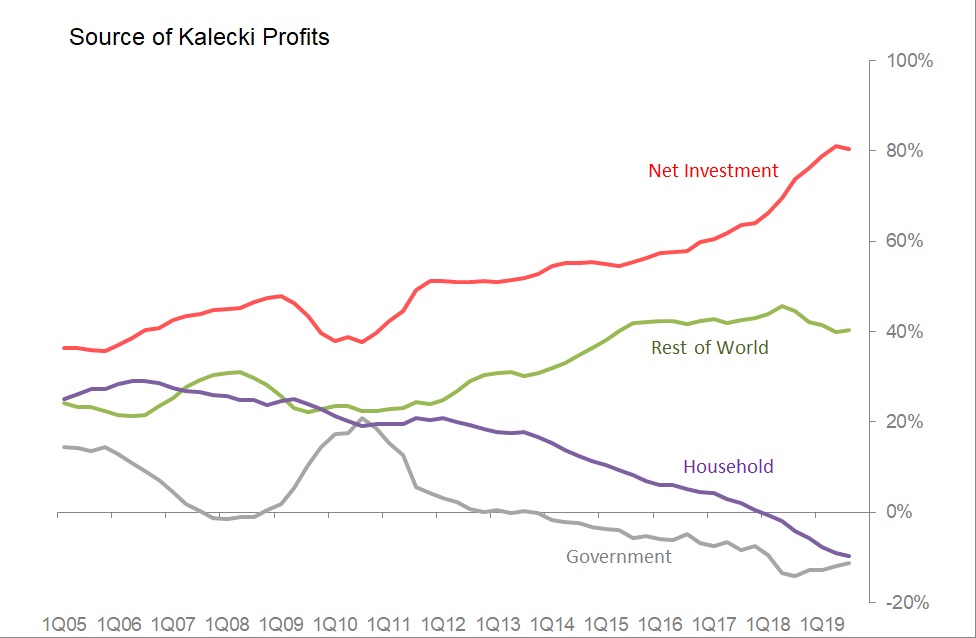

the composition of those profits remains overly-dependent on investment spending, and;

the composition of Germany's investment spending is now over-reliant on (counter-cyclical) construction spending.

Our calculation of Kalecki profits suggests profits fell 0.8% yoy in the 12m to September, despite rising 2.7% qoq. By my calculation, Kalecki profits fell 0.8% yoy to Eu489.3bn in the 12m to September. This is down 20.1% from the 3Q10 peak, and it is far from certain that the steady drift down seen since 2016 has finally been reversed.

Moreover, the source of those profits is increasingly vulnerable to cyclical forces. During the last 12 months, only two of the four possible sources of profits are contributing positively: net investment still accounts for 80.3% of the profits, and the trade surplus with the rest of the world accounts for a further 40.4%. Meanwhile, since 2018 an increasingly conservative household sector spends less than it earns in wages and compensation, and that net saving strips an amount equivalent to 9.7% from Kalecki profits. And since the government remains in modest net surplus, this too strips an amount equivalent to 11.1% from profits.

But the net investment contribution looks to have peaked: it added Eu28.8bn in the 12m to September, retreating for a second quarter from the Eu32.6bn contribution made in the 12m to March. Meanwhile, the trade surplus added Eu21.7bn, the negative contributions from the household sector came to Eu26.8bn, and from government the negative contribution was Eu15.6bn.

The slowdown in net investment's contribution is, of course, exactly what one would expect to happen as a result of the sustained fall in ROCDI. If anything, the surprise is that the slowdown in the growth of capital stock has not occurred earlier, and been more marked. I estimate capital stock was still growing by 4.9% yoy in 3Q19, with the rise unabated since 2Q15. Needless to say, this continued rise is in the face of the likely continued fall in ROCDI and the continued fall in Kalecki profits. The danger is that any slowdown in investment spending generates negative feedback consequences for profits in the short to medium term: ie, it implies a continuation of the down-phase of Germany's business cycle.

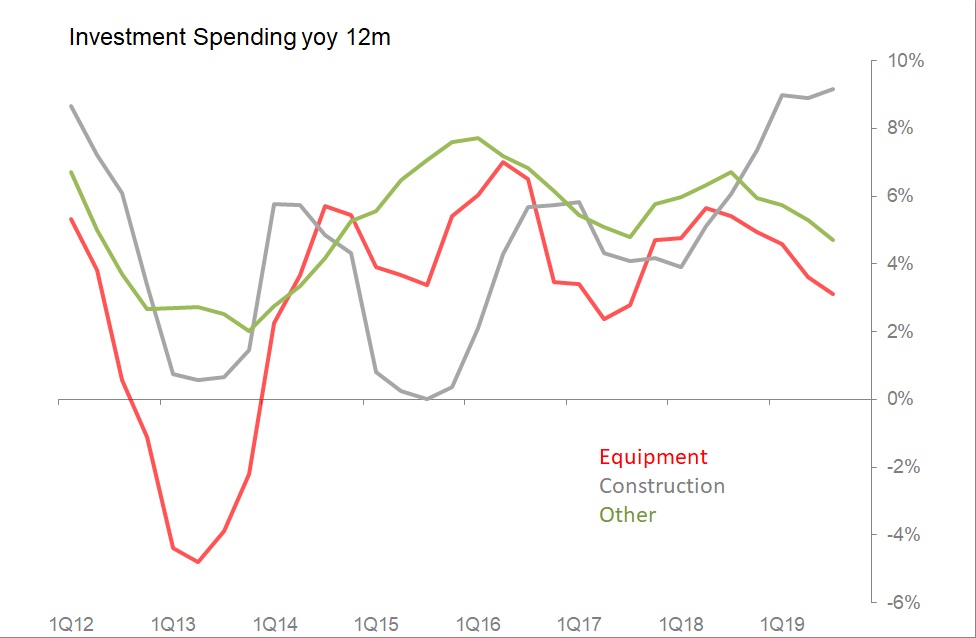

And there is a further cause for concern: Germany's investment spending is increasingly concentrated in construction. In 3Q, investment on construction rose 8.8% yoy and 5.7% qoq, and was responsible for 77% of the total yoy rise in investment. By contrast, investment in equipment rose only 2% yoy (and fell 4.5% qoq), and 'other' investment rose 4.2% yoy (and 1.4% qoq). Generally speaking, one expects lower returns on construction investments in the short-to-medium term than investment in equipment, so although there is plainly a degree of 'catch-up' involved in current construction spending, it is unlikely to boost profits or return on capital in the short term.