Jan 08•7 min read

The Humber River Delta: A Fantasy

Leaving the EU gives Britain the opportunity to break free from an economic policy-set which is not only internationally uncompetitive, but in some cases specifically damaging. Naturally, there is great reluctance in Europe generally to acknowledge policy failure, but the data is in, and is fairly conclusive: if we proxy the world economy as US, Eurozone, Japan and China, then between 2008 and 2018, the Eurozone's share of dollar GDP fell from 36.5% to 25.7%, a fall of 10.1 percentage points. The excuse that this merely reflects China's rise is belied by the facts: during the same period, the US's share actually rose 1.1pps to 39.3%, and Japan's share fell only by 3.9pps. (Although China now has roughly the same dollar GDP as the Eurozone.)

The EU policy mix of de jure protectionism (aka 'Customs Union'), de facto regional protectionism (aka 'Single Market'), fiscal inflexibility (aka 'Stability and Growth Pact'), regulatory enthusiasms (aka 'Single Market'), and a demographically-driven repulsion towards corporate restructuring and labour market liberalization (aka 'Social Chapter of the Maastricht Treaty), is an international hobble on Europe.

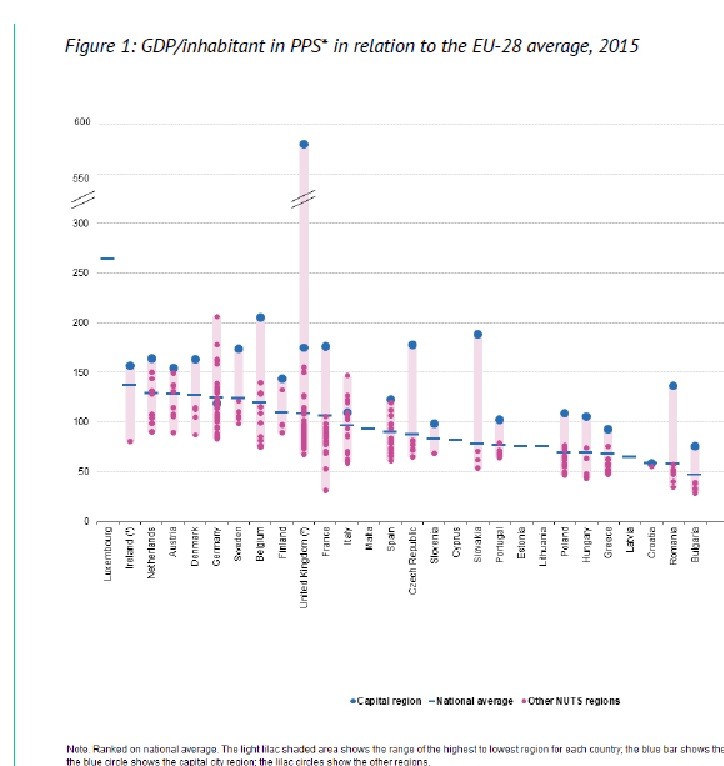

But within that generally discouraging picture, there are winners and losers. This is tremendously obvious within the UK. As the de facto capital of Europe (sorry Paris, sorry Berlin), London has benefited hugely from the influx of talent and capital. Elsewhere . . . not so much. In the most general sense, the divorce between London's prosperity and results elsewhere in the UK are well known, but particularly well illustrated in Coyle & Sensier's July 2018 study of UK public investment criteria 'The Imperial Treasury'. In a European context, the disparity between London and the rest of the UK's regions is, quite literally, off the charts.

But even within that anomalous picture, some areas fare better than others.

Which brings us to the Humber River Delta - a frankly depressing slice of the eastern coast of England with a population of about 500,000, who's major towns are Hull, Grimsby and Scunthorpe. Hull used to be important, which is why it bombed to bits during World War 2. Perhaps it never could have recovered, but certainly the last 20 or 30 years of policy-failure have accelerated its relative decline. If you have or had any ambition, this is a place you'd make very sure you got out of early.

And you'd have been right. Here are the numbers:

In 1997, Hull residents per capita gross disposable income was only 56.2% that of London; by 2006 the ratio had fallen to 51.3%; by 2016 it was down to 49.3% - less than half. For the UK as a whole, Hull's per capita disposable income is only 68.9% of the national average.

In North Lincolnshire (home of Grimsby and Scunthorpe), the decline was, if anything, more vertiginous: in 1997 per capita disposable income was 70.5% that of London; by 2006 that had fallen to 61.9%; by 2016, it was down to 55.2%. It's disposable income has fallen to 77.2% of the national average.

In fact, in the 10yrs between 2006 and 2016, North Lincolnshire's per capita disposable income actually fell in real terms, with a nominal rise of 17.6% compared with a CPI rise of 20.6%.

The failure this describes is not transitory, not cyclical, and not self-correcting: rather it is fundamental, extended, and systemic with active negative feedbacks. But worst of all it is also unaddressed, unremarked, and unlamented - a tribute not only to profound policy-failure, but also an absolutely entrenched and fundamentally apolitical complacency and/or indifference. It is merely accepted as an inevitable degradation - although had it been the result of natural disasters, doubtless there'd be no shortage of policy ready to rectify matters.

No-one who has watched what has been achieved through a multiplicity of regionally-targetted policy initiatives around numerous sites throughout Asia during this same 20 years can find this level of sustained policy disaster tolerable. It is a disgrace: a political, bureaucratic, imaginative and sympathetic disgrace.

How can British and European policymakers have learned nothing from China, from Taiwan, from South Korea, from Singapore, from Penang? Not that any of these necessarily have an 'oven-ready' set of fiscal and industrial policies which should or can be applied anywhere, but the lesson that the right policy-mix can produce spectacular results has been taught time after time after time in Asia during the period in which the Humber River Delta has been left to rot.

At this point, we have to be absolutely honest: the blame for this policy-disaster is not the EU's alone. Rather it is shared by British policymakers, and in particular the inadvertently malign long-term workings of the British Treasury's guidelines governing public infrastructure investment (set out in the Green Book, and well-critiqued by Coyle and Sensier in The Imperial Treasury).

But the perhaps instinctive British rejection of active industrial policy was given great comfort and support by the EU’s single market / competition policy. That policy essentially outlawed any state-aid to companies or industries, even in cases where the failure of entire industries left an industrial workforce jobless. The main exceptions were for public investments in the cultural and recreational sectors. Which is why, when the Tyne and Tees lost shipbuilding, they got not a new industrial vision, but rather The Sage concert hall, and The Baltic modern art gallery. It is why instead of an industrial or transport sector, Hull can now boast a splendid aquarium (The Deep), and why in 2017 the UK awarded Hull the grand prize of being its nominated 'City of Culture'.

Some consolation prize.

The British public voted repeatedly to leave the EU, and the vote was particularly marked in the Humber River Delta. Hull was 67.6% leave vs 32.4% remain; Scunthorpe was 68.7% vs 31.2%; Grimsby 69.9% vs 30.1%. In the 2019 election, Grimsby and Scunthorpe both broke historical patterns to vote Conservative, and Labour hung on in Hull with sharply reduced majorities. As much as anything else this was and is a rejection of the 'business as usual' policy-set, both national and supra-national, which has failed this region so badly.

So as Britain breaks away from the EU-mandated policy-set, and its political establishment receives a clear message that change is needed, it is perhaps time for some fantasy economics. It is time to wonder what sort of 'Special Economic Zone' policies can and should be developed to allow the Humber River Delta to have a shot at generating the sort of commercial and economic excitement we've seen so regularly in Asia. What sort of tax policies, investment policies, planning policies, labour market policies, infrastructure policies, financial policies even, would work? What sort of devolution of local administration to enact, finesse and change those policies as the situation demanded would work?

Crucially, what democratic arrangements can be made to ensure that these policies receive explicit local/regional democratic approval. For we can be sure that policies imposed centrally in the face of majority local opposition will fail (and will deserve to fail). (Even anti-democratic China realized Shenzhen wasn't a project to be run by and from Beijing.) More, getting democratic approval for radical 'Special Economic Zone' policies would go a long way to disarming the inevitable (London-based) ideological opposition. Commentary in the UK often decries and laments the possibility that Britain might become a 'Singapore on Thames'. But whilst that might not be appealing in London (and note the assumption that it would be 'on Thames'), the chance to be 'Singapore on Humber' might be something the Humber Delta would vote for. Why not? After all, Singapore's 2017 per capita GDP of approximately £41,800 might look attractive to voters in Hull (gross disposable income of £13,380), or North Lincolnshire (£14,990).

Maybe the citizens of Hull, Scunthorpe and Grimsby might see these opportunities not as a 'race to the bottom' but as a 'race from the bottom'.

Who's to say they don't have the right to vote for policies which given them a chance of vast and rapid economic improvement? If the British government puts in place special development zone policies for the Humber River Delta, and gets local democratic approval for them, I'm investing in Hull, Grimsby, Scunthorpe. Hell, I might even move there myself.