Dec 18•10 min read

Paying Attention

“There are some resources we hold in common such as the air we breathe and the water we drink. We take them for granted, but their widespread availability makes everything else we do possible…the valuable thing that we take for granted is the condition of not being addressed…Attention is the thing that is most one’s own: in the normal course of things, we choose what to pay attention to, and in a very real sense this determines what is real for us; what is actually present to our consciousness. Appropriations of our attention are then an especially intimate matter.” - Matthew Crawford in 'The World Beyond Your Head'.

People started warning me about 'the surveillance economy' a couple of years ago, and I wasn't bothered. Why should it bother me that Google and Amazon know more about my choices and preferences than I do myself? If that allowed them to anticipate the choices I'd be likely to make, then so much the better. It has taken up to now for me to realize what this is about, and why it matters. For 'the surveillance economy' isn't really the problem. It only exists because it the surveillance industry is the main supplier to the 'attention economy'. The ability to deflect, direct or distract your attention is the prize that the surveillance industry is bent on winning.

There are at least two ways of looking at this. First, and most obviously, that ability to acquire your attention is valuable because it looks like a pre-requisite to making a sale, triggering a purchase. Don't assume that if the internet of things takes off, it will ease the commercial war for our attention, the extra time gained by your fridge doing your own grocery shopping for you will merely provide an extra few minutes of your time which can be fought over. The attention economy can, I think, never actually be saturated. Soon enough, people will be selling us machines to sift through the various unwanted commercial clamours for our attention. Scrub that - email-filtering services are standard issue and getting ever-better.

The second way of looking at it is, maybe, a touch more radical. Your attention is your time, and your time is the only resource I know for certain is limited (because we're all going to die). Not by coincidence, the way we negotiate this limited resource is . . . by money. Money is what mediates between time and desire. ('With my mind on my money, and my money on my mind.')

The 'attention economy' is therefore all about money at an absolutely fundamental level.

But this truth is formidably disguised. After all, we all love the grab-bag of 'free' services offered by the internet giants. Where would we be without Google? Where would I be without Google? It takes a moment's quiet reflection (which you aren't going to get without trying) to realise that there's a cash cost to every raid those 'free services' make upon our attention. That price of that raid could at its bluntest, simply be the price you pay for a good or a service which until just this moment you didn't know you wanted. But it could also be in the erosion of the time you have available to do other things (including, but not limited to, 'productive work').

Worse, it could be in the erosion of the quality of that diminished time you have available to do other things. In other words, you are also paying a price in a structurally diminished attention-span. Specifically, your ability to concentrate on a task for a sustained period of time is eroding. A 2015 Microsoft research paper is a favourite source on this. Famously, it found that between 2000 and 2013 the average human attention span fell from 12 seconds to eight seconds, and that we're now being out-focussed by goldfish. The research found that media consumption, social media usage, technology adoption, and multi-screening behaviour were the top factors cutting our ability to concentrate.

(With absolutely no irony at all, Microsoft's research was aimed specifically at marketers, and came freighted with handy tips about how to more effectively grab that diminished attention span. In other words, this piece of research was primarily business advice about how to prosper in the 'attention economy'. It's conclusion: you've got to beaver away at eroding its foundations even more aggressively, sorry, innovatively.)

There are identifiable and potentially measurable short, medium and long term cash costs imposed by these 'free' services.

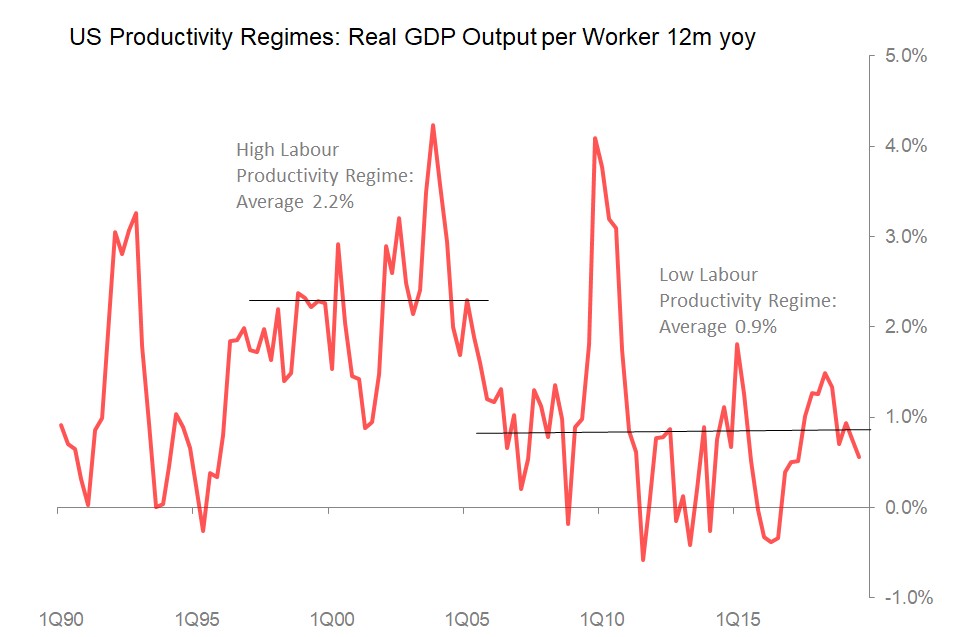

Those of us old enough can remember the time when the explosion of connectivity and information-availability promised to give us un-thought of powers of productivity. The internet was a world of new productivity-raising tools. That time was approximately the early-mid 1990s. What has happened to developed world productivity as these productivity raising tools have come into our hands?

Throughout the developed world the story is the same: we live in a world of diminished productivity gains. Why has it happened? Economists have provided such a multiplicity of explanations that we can properly say this ailment is 'over-determined'. Still, I suggest we should add to the list of culpable factors, the negative economic impact of the rampant development of the 'attention economy' which has been based on the internet.

At this point, it is perhaps worth thinking about the parallels between the long-term malign impact of 'free money' monetary policies, and the malign impact of 'free services' on the attention economy. Intuitively, one would expect them to be connected, since negligible interest rates and associated near-flat yield curves imply there is no anticipated future desire or investment worth funding at the cost of restraining current spending. Put another way, current attention spent now elbows out of the way the expected return on sustained attention. Why buy War & Peace when there is Instagram to entertain us?

The long-term negative impacts of zero or negligible interest rate policies include:

a reallocation of wealth to those already holding assets such as property, which in practice has tended to result in greater inequality, including inter-generational inequality, and;

the suppression of the 'creative destruction' which is one characteristic of successful market economies. More specifically, it preserves and encourages 'zombie companies' which depress return on capital, erode margins for non-zombie companies, and thus actively suppress capital investment and hence productivity.

Is there an analogy with the provision of 'free services' which appropriate your attention? I think there must be: the reduced attention span looks to me like a flattening of the attention-yield-curve, in which the future expected value of sustained attention now is insufficient to offset the value of the current attention sacrificed now. Even if the rewards to that current attention are actually negligible or even negative. (Don't tell me you haven't regretted time wasted on the web - of course you have.)

By extension, those activities and achievements for which a sustained attention is a necessary precondition - learning to play a musical instrument, learning wood-turning or pottery, coding beyond 'Hello World' - will become rarer as 'prohibitively expensive' in the attention economy. If these 'attention-expensive' phenomena contribute valuably either to the longer-term creativity and productivity of the economy, or just as importantly, to the quality of a lived life, then 'free services' are a problem. I assert that those 'attention-expensive' phenomena contribute to both.

And so to crypto: perhaps the inevitable destination for this piece.

At first sight you would assume that crypto-currencies and neglible interest rates tango together. The argument I usually find is that negligible or negative interest rates on, say, dollar bonds simply make traditionally non-yielding assets such as gold and now crypto currencies an attractive proposition. The more negative the dollar yield, the more reason to buy Bitcoin, apparently. (Though conversely, I also note that it is now possible to earn interest on your Bitcoin deposits, although quite what companies like Blockfi do that allows them to pay their (uninsured) depositors 6.2% pa on their Bitcoin deposits is probably worth a full-bore investigation in its own right. For this to work, someone somewhere must surely, unwittingly or otherwise, be taking a massive unhedged futures position in Bitcoin. Good luck with that.)

For most crypto-currencies, including Bitcoin, their relationship to zero-interest-rates is indeed only tawdry. With its predictable limited supply and essentially yield-less infrastructure, crypto-currencies/tokens are, after all, primarily a classic 'banker's ramp' prospering when liquidity is looking for a home - any home - and suffering disproportionately if and when liquidity finds a productive home to go to.

In these iterations, the underlying problem for crypto-currencies is precisely what a director of the HK Monetary Authority identified: they aren't currency. They aren't currency because they flunk the fundamental challenge of all money, that there be enough of it around to accommodate and even encourage its use for transactions, but that there be little of it around to allow to act as a plausible store of value. These two uses of money must forever be in unresolvable conflict, and indeed, the structure of the yield curve is the principal way in which a temporary and always-changing armistice between the two demands is maintained.

Usually crypto-currencies/tokens simply pride themselves on the transparency with which future supply is limited. This is why the most expensive pint of beer ever bought was the one paid for in Bitcoin at a 'bitcoin-accepting bar' in New York circa 2013 (when a Bitcoin went for cost $13.4). Who'll be making that mistake again? In short, it's not currency.

One crypto project, however, looks fundamentally different: Blockstack. The reason is two-fold. First, and most importantly, Blockstack's entire raison d'etre is to reclaim ownership of your identity from the attention economy. Own your online identity, and you secede from the main instruments of the attention economy, since your interests, your activity, your online soul, cannot be separately identified by suppliers of feedstock for the attention economy (ie, Google, Facebook and the rest of the gang). But by the same token (pun intended) your Blockstack identity will potentially allow you to interact with the rest of the online world on your own terms.

But this Blockstack-friendly environment is unlikely to be 'free', since it does not yield the valuable information about you which the attention economy covets. Rather, the services are likely to be paid for, in Blockstack tokens. And since there is actually a value attached to your attention span, then in theory, the value of the Blockstack token you use to defect from the attention economy will discover it. Counter-intuitively, then, the most important thing about the Blockstack token (called the Stacks) in the near future is precisely that it does not become hostage to the preservation of value function of money, and that it does not find itself 'soaring in value' on the back of a general upsurge in crypto-mania. Rather, if it is to succeed, it is crucial that there are enough Stacks around to allow for its use as a currency for attention-economy defectors.

It is, I think a noble and probably necessary aim. Consequently, this blog is part of the Blockstack world; one of my redundant storage solutions is in the Blockstack sphere; I have a Blockstack D-mail address, and as the environment develops I fully intend to migrate as much as possible of my online activity to Blockstack-friendly environments.

This piece has taken me several days to write, and, if you have finished it, you're probably thinking it took an uncomfortably long time to read. If you made it to the end, then statistically you're doing well. I did my best, I hope it was worth it.