Jun 08•7 min read

The Wrong Super-Cycle

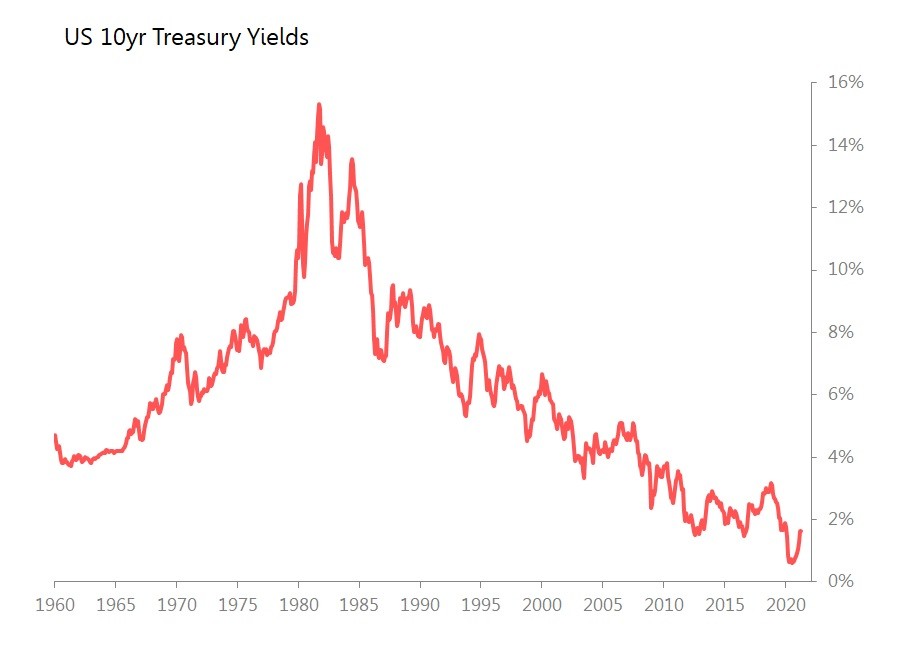

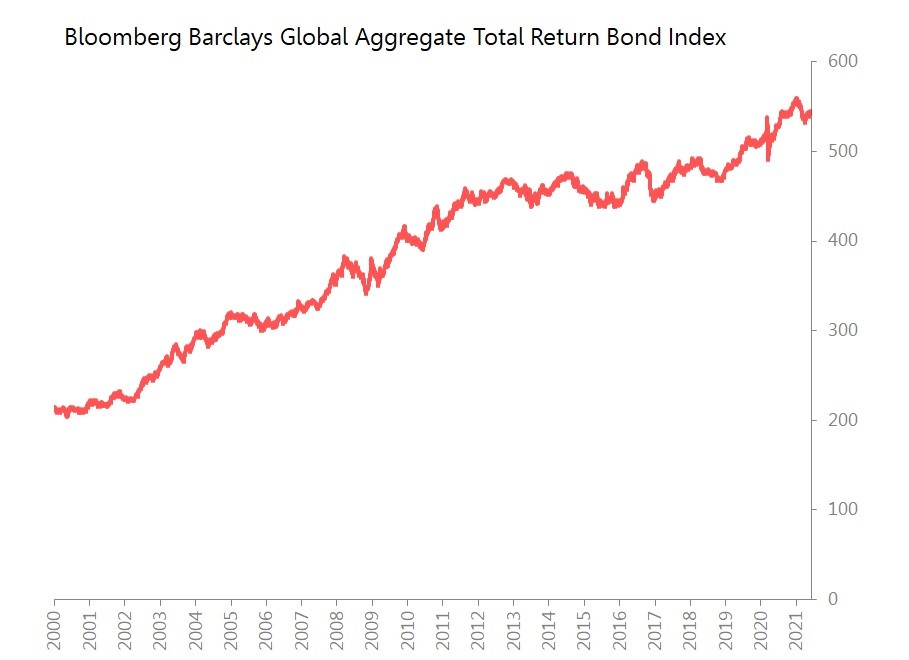

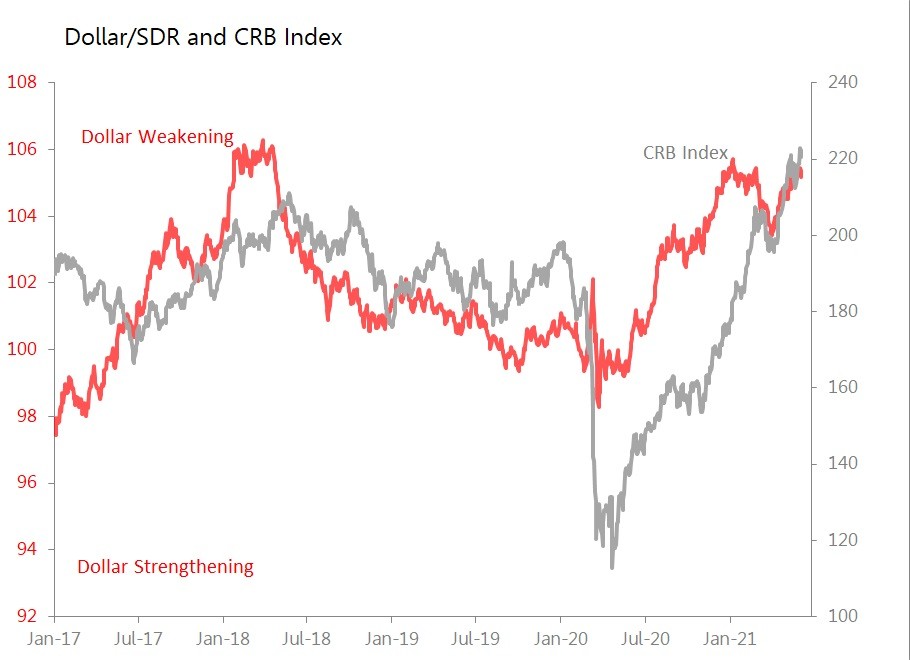

The rise in commodity prices - the CRB index is up 95% in dollar terms since its pandemic nadir of April 2020 - has encouraged the view that a new 'commodities super-cycle' is hoving into view. The justifications offered are unconvincing. The real super-cycle the current price rises are telling us about is the belated end of the financial industry super-cycle which was initiated when Paul Volcker arrived at the Fed determined to tackle inflation. The result was a generations-long uninterrupted bond bull market which reached its natural peak around the turn of the century, and extended through to around 2010, ironically by responses to the multiple crises actually generated by the end of the cycle. The final extension has been granted only by the utterly unprecedented impact of a global pandemic, which has left central banks have become the main supporters of government bond markets.

The last buyer is in mid-buying climax.

This cannot and will not last, but in the meantime contributes to a number of price distortions, of which the current volatility of commodity prices is but one. It distracts from the far greater likelihood that we are at the end of a decades-long financial market super-cycle, and that the prospects for financial assets are under attack from forces which look entrenched in the medium and long term.

The arguments advanced for a new commodities super-cycle are surprisingly weak: President Biden's infrastructure-plan ambitions, global investment in renewable energy, and a rise in lower-income earnings in developed countries which will encourage relatively strong consumption of stuff rather than services.

The first factor - President Biden's infrastructure ambitions - is among the least-convincing, since it assumes that a) the plans will encounter no effective political opposition, even after next year's Congressional elections; b) that money allocated will actually be spent on built infrastructure rather than consultants and various types of social benefits; and c) there will be no countervailing drop in private demand if a significant portion of the spending is financed through tax rises.

The second factor - the global push towards renewable energy - ignores problems of scalability of wind and solar power which on close examination seem impossible to finesse. . They also ignore any possible democratic pushback against policies which look very expensive both in terms of taxes and energy prices (ask Emmanuel Macron, ask Angela Merkel) . (The unspoken factor is that only nuclear power will be able to replace fossil fuels in generating electricity in sufficient size. So there is a strong case for a bull market in uranium at least.)

Probably most damaging of all, they ignore the impact of rising interest rates on 'green technology' economics. Where green technologies differ from existing power-production technologies is precisely that they are high fixed-cost, low variable cost propositions, compared to the low fixed-cost, high variable cost structures of, say, fossil fuel power generation. Consequently, the economics behind green power generation deteriorate disproportionately in times of rising interest rates.

The third proposed factor - a recovery in the relative position of lower-paid households in developed countries, leading to a rising propensity to consumer stuff rather than services, is unproven in every clause.

The justification for the most recent commodities super-cycle was unambiguous and observable at the time: it was China's ability to lift hundreds of millions of its people out of grinding poverty over a relatively short period of time. This was the largest poverty-alleviation achievement in human history. It was also clearly a signal that there would be an unprecedented rise in demand for the stuff that made stuff. Since it was by far the biggest story in global economics, it has also been one of the most closely followed.

Where are the demographic candidates for a repeat of this achievement? It would have to be either Africa or the Indian subcontinent. Any takers?

Rather, there is a powerful and widespread demographic factor which generates unavoidable headwinds for a commodity super-cycle: the aging of all the world's major economies, and the falling populations of many of them. These demographic trends are more favourable to downsizing, the dumping of goods accumulated over a lifetime, and a heightened demand for services, than the rush to accumulate goods typically seen during the early years of adult life.

Given the long odds against it, the desire to proclaim a commodities super-cycle is interesting, suggesting a desperate desire either to declare a viable inflation-hedge or, alternatively, to open a bolt-hole against the end of the financial industry super-cycle. The alternative view is that commodity prices are being bid up by a combination of dramatic monetary easing which has opened up a dramatic but temporary mismatch in the timing of shifts in demand and supply curves as we move towards the end of the economic interruptions justified by the pandemic.

End of the Financial Super-Cycle

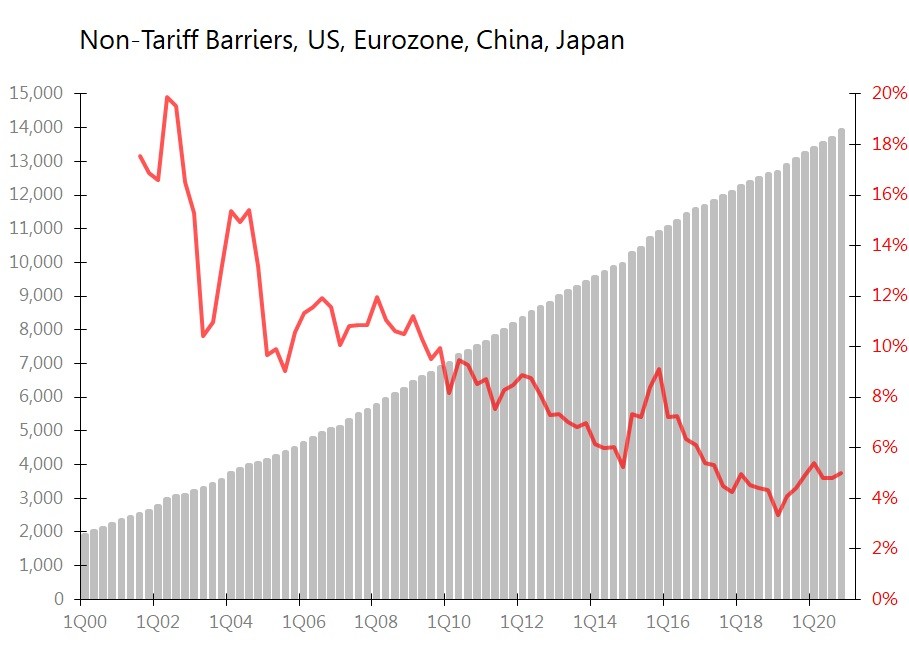

Meanwhile, quite apart from the anomalous interference by central banks with developed country government bond markets, I think there are very visible factors compelling the end of the globalization which was the economic running-partner of the financial super-cycle. These factors are all, in the end, political.

First, regardless of the rhetoric, no major country is really committed to free trade - rather, they relentlessly legislate to restrict trade. The evidence is in the relentless rise in Non-Tariff Barriers - a rise far quicker than the global rise in imports they aim to restrict.

Second, in response both to the birth in the internet and, specifically, the aftermath of 9/11 global terrorism, the rise in anti-money laundering regulation has discouraged international movement of capital by raising its price. Currently, to satisfy regulatory demands it costs more simply to move cash from one country to another than, say, to buy shares. In the long term, restricting international capital flows is a brake on globalization. Since globalization is plausibly credited with maintaining consumer disinflation across a broad swathe of goods, discouraging globalization is likely to come at the cost of less disinflation generally. That has negative implications for global bond markets in the medium and long term.

Third, the rise in inequality in developed countries coupled with the rise in profits/GDP has generated a direct political demand for de-globalization and 're-shoring'. This is a specific popular rejection of the 'cheap goods at any price' benefits of globalization which implicitly anticipates higher prices. Again, this is bad for bond markets - and hence financial asset pricing - in the medium and long term.

All This and the China/US Contribution to Covid

To these factors, this week has added another factor, potentially the most powerful and dramatic of all. That factor is the abandonment of the previous global campaign to outright deny the possibility that the pandemic might have virus escaped from the Wuhan laboratory after 'gain of function' modification. The implications for the structure of the world economy, and for China itself, are incalculable. Indeed, the terrifying consequences of it being found that this pandemic originated when (partly US-funded) Chinese virus-engineering met lax Chinese safety standards probably partly explains the profound reluctance to entertain the possibility, and the broad-spectrum official and corporate attempts to denounce anyone contemplating it.

Even though it has always seemed the most likely source.

With millions dead, further millions unemployed or bankrupted, and trillions lost in economic output, the 'accident at Wuhan' - if that is what it is - dwarfs Chernobyl, dwarfs 9/11. But like 9/11, like Chernobyl, it is probably a moment which fundamentally changes everything. And again, in a way which is profoundly bad for globalization, and for financial markets in the medium and long term.

The idea that a globalized economy will be maintained, whilst one pole of it revolves around an unreformed China, seems very difficult to contemplate. No wonder the urge to suppress the possibility was so urgently indulged not just by China but also by US corporations with the energetic connivance of both legacy and social media powers.

In short, the long and wonderful financial super-cycle which has accompanied the almost wholly beneficent economic globalization, is staring at its end. It will take more than dreams of a new commodities super-cycle to head it off.