Dec 12•2 min read

Britain: Why the Cycle Needs a Government

Today is election day: but almost certainly it won't bring the great political realignment and policy re-invention which must inevitably appear over the next few years. If the Conservatives squeak through to a workable majority, we can expect sufficient capital spending rebound to fend off recession in 2020.

But while we wait for the necessary policy re-invention, the current weaknesses undermining the UK economy will tend to reassert themselves in the medium term, even if the downturn is finessed in 2020. Taken together, these paint a rather grim picture, one in which underlying stresses for business and for households are expressed and then compounded by the extended political paralysis which has followed the electorate's withdrawal of consent to continued membership of the European Union. Unaltered, this set of circumstances points to recession. Hence the crucial importance of resolving the political deadlock: the cycle needs a government.

Let's look at the structural flaws contributing to Britain's current cyclical vulnerability, which can be summarized as:

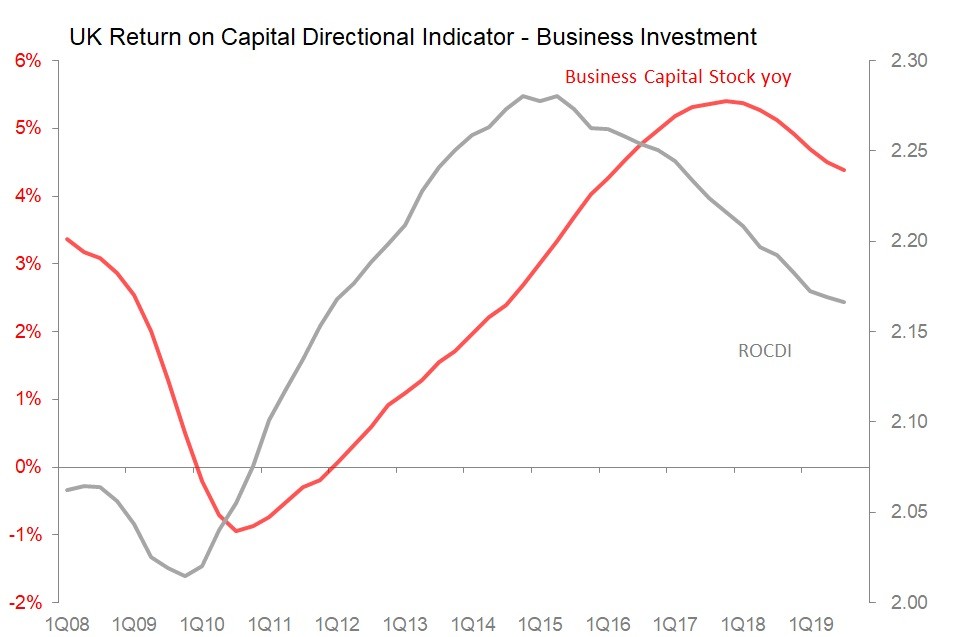

return on capital peaked in 2015, with the result that business investment, and capital stock growth, has slowed. In nominal terms, gross fixed capital formation growth slowed to 2.5% yoy in the 12m to 3Q, with business investment slowing to just 1%. Even so, my return on capital directional indicator continues to decline.

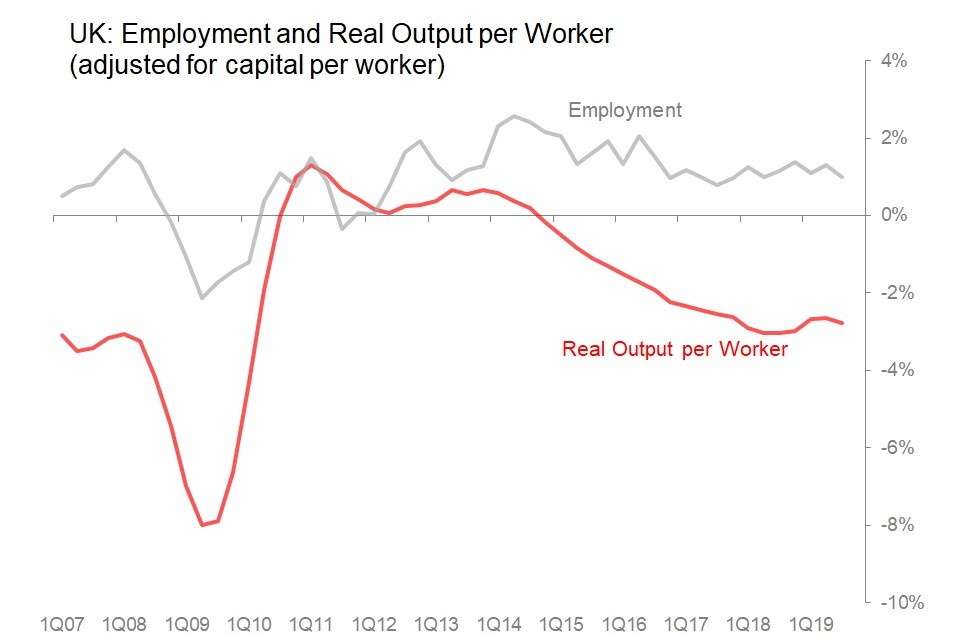

Although employment continues to grow, real output per worker, when adjusted for capital per worker, is falling approximately 3% yoy. In fact, the decline in real labour productivity is now slightly faster than the 1998-2008 trend. Continued strong employment growth is not, therefore guaranteed.

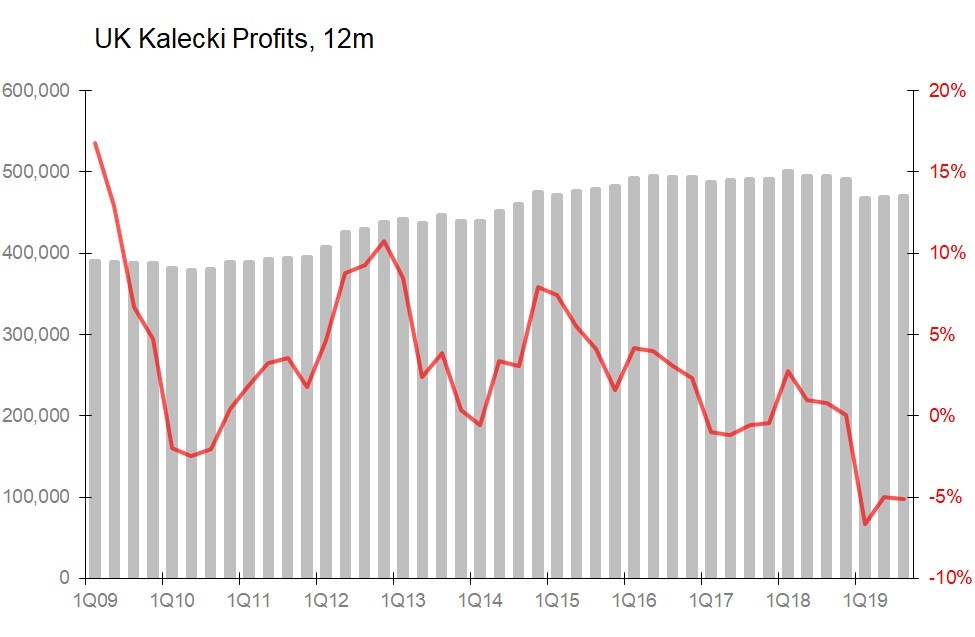

Not surprisingly, my calculations show Kalecki profits peaked during 2016 and maintained that nominal plateau until this year. In the 12m to September, I calculate they fell 5.1% yoy. In fact, this is the sharpest and most sustained fall in profits this century, including during the aftermath of the financial crisis. As a percentage of GDP, Kalecki profits have fallen to 21.4%, down from a 2016 peak of 25.4%, and the lowest since 2007's 20.9%.

Partly as a result of the profits fall, the UK private sector as a whole ran a savings deficit equivalent of 3.2% of GDP in the 12m to September. In other words, the financial system is having to provide a sizeable positive cashflow to the private sector in order for it to maintain its current rate of investment and consumption. Usually, this means more debt.