Feb 09•13 min read

The Recovery of 2021

'If I were you, I wouldn't start from here'.

In 2021, Western economies will discover the early stages of recovery from the epic dislocations which accompanied the pandemic in 2020. Quite what this means is already being fought over by economists, central bankers and politicians, in a cacophony of contradictory forecasts, proposals and warnings. This reflects the remarkable degree of uncertainty about the pandemic's evolution itself, and also its likely long-term impact on economic and political behaviour. This piece will ignore those long-term issues, but will try to narrow down the range of the likely for the coming 12-18 months.

And its main conclusion is this: it is difficult to expect the sort of recovery which would return the US economy to full capacity in 2021, or even in early 2022. It is difficult to construct a case for full employment. It is difficult to construct a case for a dramatic investment-led economic surge. It is difficult to expect the sort of fiscal stimulus which would overturn some very difficult 'delta' issues on the government deficit. It is difficult, therefore, to expect a great inflationary outbreak in 2021. Rather, this year, is likely to be one in which the economy searches to discover a new foundation for its next cycle. That cycle will emerge, and will generate formidable challenges, but 2021 almost certainly isn't the year when those surface.

The problem for post-pandemic economies is that 'recovering to pre-pandemic levels' is no recovery at all. Because, after all, a recovery to 2019 levels of activity implies a large measurable loss of potential output, potential activity, upon which previous plans for capital spending and employment were based. Merely regaining the levels of economic activity seen in 2019 is no recovery at all, nor should it be expected to generate full employment or trigger an investment-led business cycle upswing.

These, at any rate are my best guesses. But those guesses are based on tracing the various plausible trajectories of growth, employment, productivity, return on capital and capital spending. This is probably useful, but also quite possibly deceptive, since the maths generates a specificity which is quite spurious. In all economics, this sort of specificity is spurious, since no-one has ever worked out how to forecast economies with reliable accuracy. But right now there is a worse problem: the only experience we have are 'recoveries from recession', but, of course, the closure of developed economies in 2020 was not a recession, it was a government-mandated shutdown. No-one really knows what happens next.

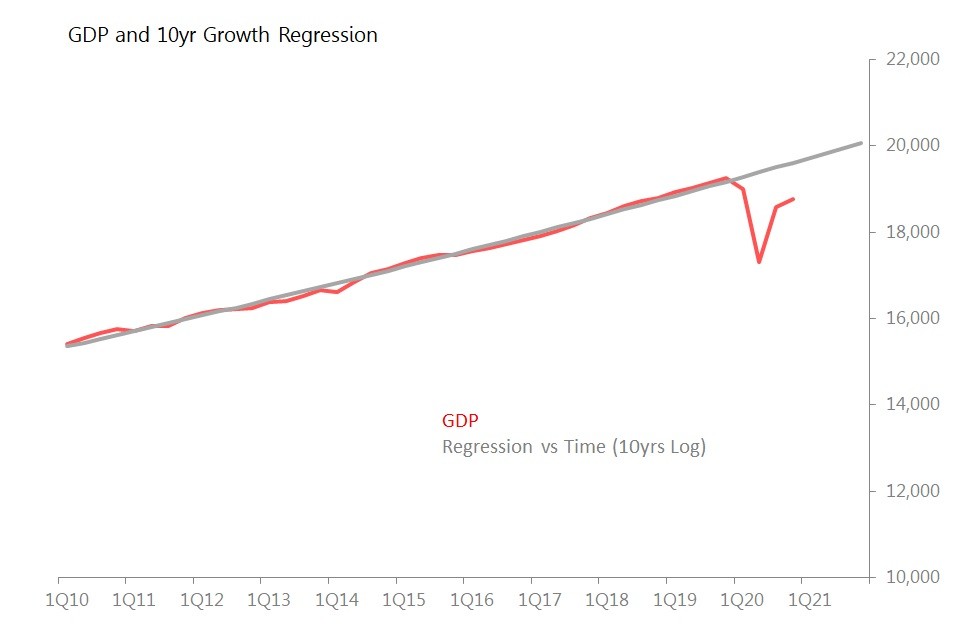

Nevertheless, here goes. First, using the US as our model, let's consider the position at the end of 2020. The national accounts for 4Q20 show seasonally adjusted 'real' US GDP 2.5% below the level of 4Q2019, and growing at almost exactly 1% qoq sa. However, it is also 4.3% smaller than it would have been had the 10yr trend growth rate have been maintained. Still, that 1% qoq 4Q growth rate compares with a 10yr trend quarterly growth rate of 0.57bps, so although immediate bounce-back numbers of 3Q have slowed sharply, the growth rate is still considerably faster than trend. That's the good news.

However, it isn't going to solve all problems. If that quarterly growth rate of 4Q is maintained, then the economy will have recovered to its pre-pandemic size by the middle of 3Q21. But that still leaves it some 3.5% smaller than the economy would have been had there been no pandemic interruption. It will still, in other words, be smaller than investors and employers would have been expecting: by the end of 2021, it will still be 2.6% smaller than you would have expected the day before the pandemic lockdowns were imposed.

If the US economy is, in 2021, to recover the ground lost in the pandemic and rebound the economy to the size investors and employers had expected in the days before the pandemic, it will need to maintain a quarterly growth rate of 1.7% qoq throughout the year. That's a growth rate which annualized to a sustained 7%. Since 1990, excepting the rebound result of 3Q20, a quarterly growth rate annualizing to 7% has been achieved only twice: in 3Q03 and 2Q02, It would be a strange economist who expected that to be repeated four times in 2021. (In the US, manufacturing industry has been producing to meet the 'pent-up demand' expected but not so far witnessed, its work backlogs have shrunk to the lowest since 2013 - hardly an encouraging sign.)

Reduced Expectations and Growth Factors

So even as recovery is underway, we have to recognize that in the medium term, the lockdowns of 2020 will result in an economy which is smaller than anyone could have anticipated the day before it hit. Not only was the future in 2020 not what had been expected, but the future in 2021 isn't what was expected, and most likely not in 2022 either. If decisions on capital spending and employment are to a large extent based on medium and long-term expectations - and I think it is axiomatic that they are - then recovery to pre-pandemic levels will not result in pre-pandemic levels of employment and investment.

Growth Factor: Labour

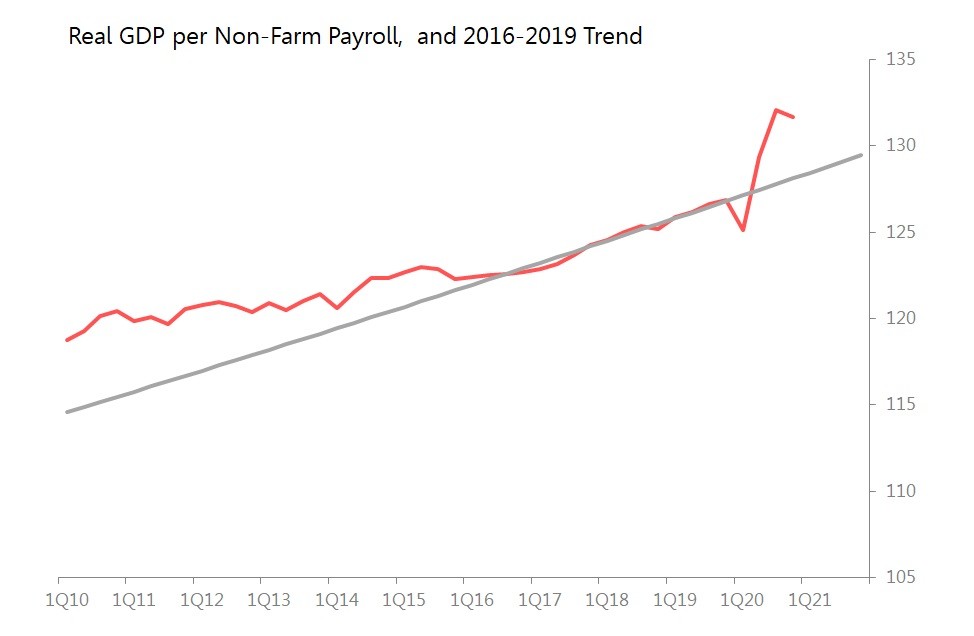

Taking the next step, we'll consider what this means for employment. The starting point is to understand the governing trends in GDP per employee, shown in chart below. What it shows is a fairly clear trend growth rate pre-pandemic, which was sharply disrupted in counter-intuitive ways by the pandemic and the subsequent government furlough schemes. (The commercial reality of this was revealed in the 4Q unit labour costs and productivity numbers, with output per worker per hour up 2.5% yoy, but unit labour costs also up 5.2% - the result of a smaller workforce actually turning up, whilst a wider penumbra of furloughed workers being maintained at least partially on the books.)

One of two things can happen: either the economy experiences a one-off jump in productivity, as furloughs continue, or the GDP/non-farm payroll trend ratio observed between, say 2016 and 2019 is re-established. If one is looking for a recovery in employment, of course, one hopes that the one-off productivity jump is reversed, and the underlying trend does in fact reassert itself. That is the assumption I will be making in what follows.

Here's how the maths works out. If the trend in GDP/non-farm payrolls has merely continued throughout 2020 (rather than spiking) , then - and this is the good news - by end-2020 non-farm payrolls would be 4mn higher than they actually were - 146.575mn rather than the 142.605mn recorded.

However, what happens to those numbers if we assume that the recovery continues at the sort of pace seen in 4Q - the pace at which the economy would have returned to its pre-pandemic levels by mid-3Q21? In those circumstances, would could expect non-farm payrolls to recover to around 150.9mn, which would be around the level achieved in 2Q19, and around a million lower than pre-pandemic levels.

But recognize that this model is unrealistically simplistic. On the negative side, quite clearly the GDP/payroll number isn't going to return to trend immediately, so even if the convergence occurs, the recovery in employment will necessarily be back-ended. On the plus side, the mild acceleration in productivity seen during 2016 to 2019 might slow or stall - in which case the number of employees compatible with the achieved growth rate would be higher.

Nevertheless, what this basic maths shows us is that 'recovery to pre-pandemic levels' in 2021 does not result in a recovery of labour markets to pre-pandemic levels in 2021.

Growth Factor: Capital

How will recovery in 2021 be related to capital spending? Will recovery be likely to trigger accelerated capital spending, or might it be initially driven by it anyway. Or, as accelerator and multiplier effects kick in, might capital spending be both cause and effect of 2021's recovery?

This is a more difficult question than it might seem at first sight. At first sight, there seems little chance of a capital spending surge, because the contraction in nominal GDP in 2020 (still down 1.4% yoy by 4Q) means that since private capital stock growth was probably still running around 4.1% yoy, the return on those assets must have dropped sharply. The chart below generates a return on capital directional indicator by expressing GDP (minus inventory changes) as an income from a stock of fixed capital, with that capital stock estimated by depreciating all private investment over a 10yr period.

As the chart shows, capital stock usually starts to resume growth some time after the nadir of the ROCDI:

In the early 1990s recession, the pickup in capital stock growth arrived 5 quarters after the nadir of the ROCDI;

In the early 2000s recession, the pickup arrived four quarters after the nadir of the ROCDI

In the GFC, the pickup arrived five quarters after the nadir of the ROCDI, but didn't show positive growth until 11 quarters after the nadir.

In 2020, the nadir was a very sharp drop in 2Q, so if previous economic history is repeated, we would expect a recovery in capital stock growth to show up sometime in 2Q21 or 3Q21.

But there are at least two reasons why we should doubt that the sort of behaviour seen in previous recessions will be repeated this time.

The first reason is quite fundamental: the sharp contraction of economic activity in 2020 is in all important ways not a recession, but rather a government-mandated partial and temporary economic closure. Recessions are fundamentally disruptions in economic flows in response to no-longer-ignorable problems in economic stocks, and those economic flows recover once the underlying stock problem is resolved or finessed. 2020 was nothing like that: the outcome for the economy was not, fundamentally, anything to do with the economy. Rather it was to do with government and societal responses to a nasty pandemic. On the plus side, then, the contraction of 2020 did not mandate a slowdown in investment spending.

Nevertheless, the economic contraction happened, and, as explained above, the normal recovery trajectories will still leave nominal GDP in 2021 and 2022 below the absolute level expected by businesses and investors back in pre-covid 2019. And the result can be seen in the ROCDI for 4Q 2020: after the rebound recovery in 3Q20, the continued recovery in 4Q did nothing more than stabilize the ROCDI at levels which are still historically low. Unlike in the three previous recessions, there is no obvious reason to expect a sustained dramatic recovery in the ROCDI in the absence of a continued slowdown in capital stock growth. This is the second reason to be sceptical that the experience of the previous three recessions will be revisited this time round.

Rather, we have to face the reality that before Covid hit, the ROCDI had been sagging gently downwards since 2014, and that this had finally begun to erode capital stock growth. In fact, capital stock growth peaked in 1Q2019, and had been slowing for five quarters before the bottom dropped out in 2Q20.

Using this information, what happens if the US economy resumes the sort of compounded nominal growth pace seen 2010-1Q2020 (near enough 1% a quarter, and 4% pa). The US economy ended 2020 approximately 4.5 percentage points smaller than that long-term nominal growth rate had expected. If 4Q20's nominal growth rate of 1.2% is maintained, then it should have recovered to pre-covid levels as early as this quarter. However, without considerable further acceleration, nominal GDP will remain smaller that it would have been for the foreseeable future, catching up probably around the middle of 2025.

However, using that 1.2% nominal qoq growth rate, and holding capital stock growth unchanged at 4.1% pa, what happens to the ROCDI ?

You can see the problem: if there is no further slowdown in capital stock growth, the prospects for a rapid recovery in ROCDI are limited. Only by slowing capital stock growth further can we expect a rapid recovery in ROCDI of the sort which, eventually would allow a recovery in capital stock growth. You wouldn't, in other words, want to start from here!

The most plausible alternatives are these: either,

Investment spending accelerates, with the result that the return on capital directional indicator does not recover, thereby preparing the ground for a subsequent investment slowdown, or;

Investment spending stagnates, with the result that the return on capital directional indicator does recover, thereby preparing the ground for a subsequent investment boom.

What is not plausible is that both investment spending and return on capital boom together. Why? Because, in a word, in the absence of a really dramatic recovery, the US will not be an economy who's growth factors are fully employed during the next 12-18 months. Much more likely, 2021 will see the economy re-stabilizing and then attempting to re-establish the sort of patterns which will eventually encourage the birth of new business cycle pressures.

Post-Script: Stimulus and Inflation

A final thought. Plenty has been written about the impact of President Biden's proposed $1.9tr stimulus package. Without knowing its details, including the probability of its deployment, its timing and how it is financed, one cannot really assess its impact. However, two things we do know. First, the maths controlling the delta of the fiscal deficit are very tough. In calendar 2020, the federal deficit came to $3.348tr, which was an increase of $2.326tr on calendar 2019. With that background, it seems unlikely that 2021's deficit could show an uptick in the rate of change of the deficit. Second, we also know from 2020's experience that some element of Ricardian Equivalence is likely to kick in to mute the overall economic impact of the fiscal stimulus. In 2020, whilst the Federal deficit increased by $2.326tr yoy, overall the household sector reduced its dissaving by around $440bn (ie, an amount equivalent to c20% of the increase in the deficit). At the same time, personal saving levels rose by $1.184tr yoy, as households held on to 'pandemic recovery cheques' the government was writing. Is there a good reason to expect that behaviour to change in 2021?

Both because the US economic recovery is unlikely to results in an economy operating at capacity in 2021, and because any the impact of any fiscal stimulus is likely to be muted both by mild Ricardian Equivalence and a slowdown in the rate of change, it seems premature to expect a dramatic inflationary outbreak in 2021.