Feb 09•3 min read

Turkey On the Turn

There are good reasons why Turkey fell off the international economic radar a couple of years ago: perverse policy choices generating a classic emerging market denouement in which overheating, over-leverage, falling returns on capital, and negative cashflows eventually undermined the currency and shattered the confidence needed to keep the show on the road. The better news is that although policy-making may not have improved, Turkey has reached that point in the crisis-cycle where the underlying ratios are improving fast: in the next few quarter, Turkey will be on the turn.

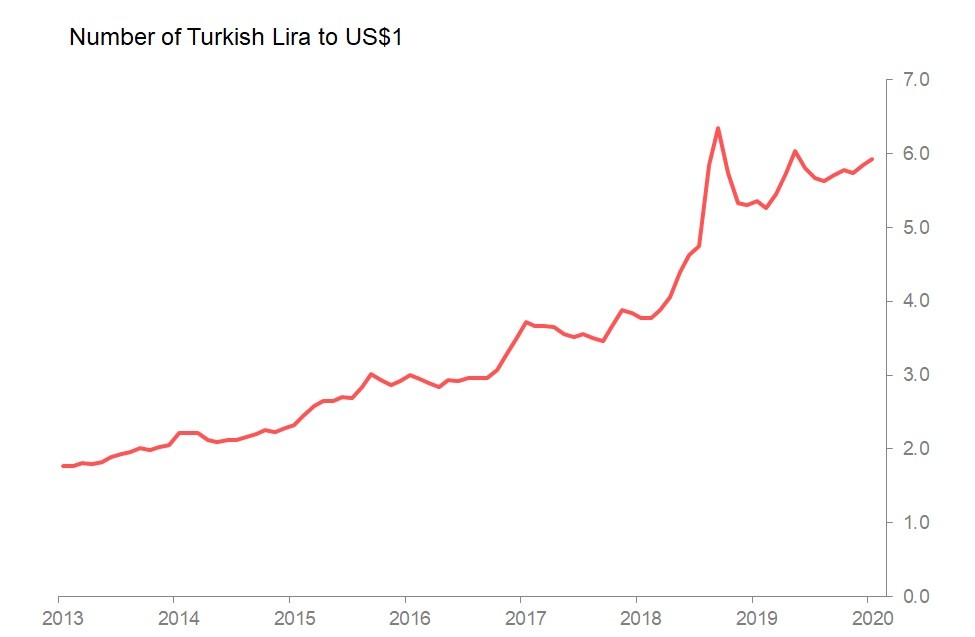

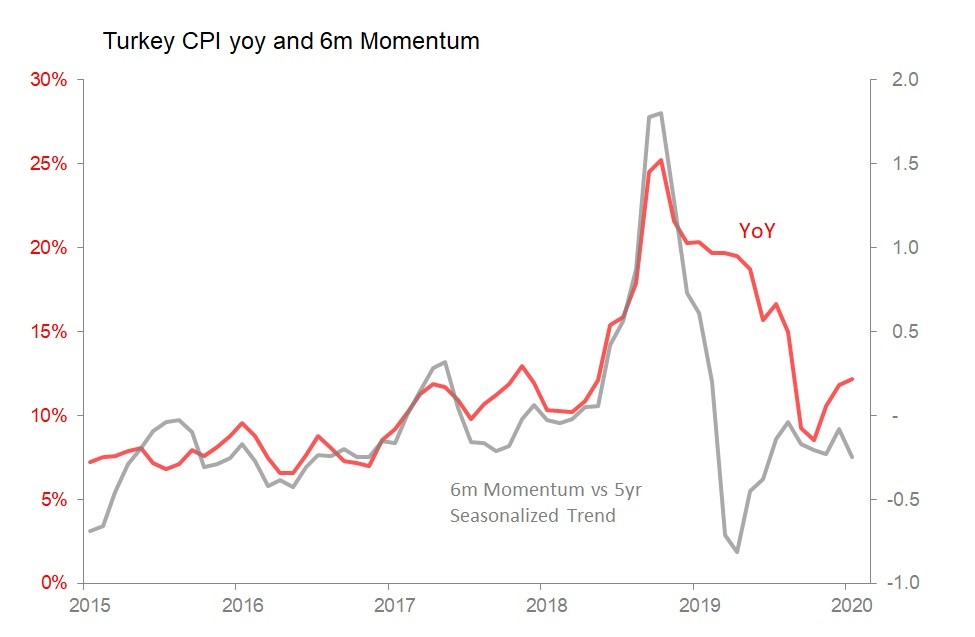

The easiest way to explain is simply to show. The inflation story is one way to start: at the peak in October 2018, Turkey's CPI topped out at 25.2% yoy, exacerbated by the pressures on the currency which took the lira from 4.8 to the dollar in July 2018 to 6.4 to the dollar in September. As so often, the damage to the currency both reflected and intensified the underlying inflationary problem, and also necessitated a response. Inflation momentum peaked in 4Q18, and has remained negative ever since. By October 2019 it had retreated to 8.6% yoy (helped by the base of comparison), rising back to 12.2% in January 2020. Despite that rise, inflationary momentum remains negative, and yoy comparisons likely to stay around 12% for the time being.

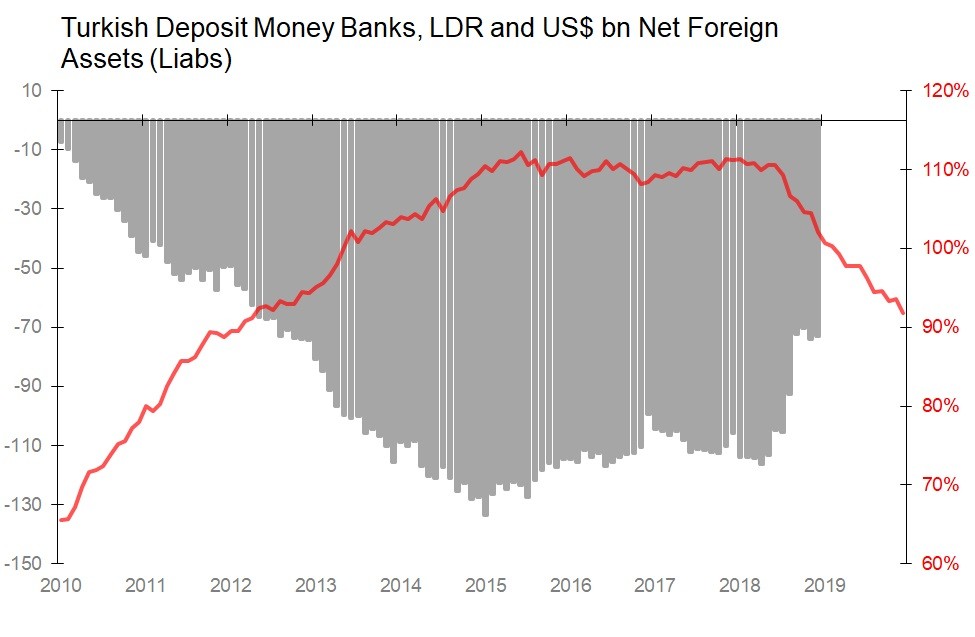

Part of the reason for the retreat in inflation is the enforced (through loss of foreign liabilities) slowdown in bank lending: from a peak of 33% yoy in August 2018, loan growth dried up completely in mid- 2019, and by the end of the year was running at only 5% yoy 12ma. Meanwhile, deposits continued to grow, achieving a 17.6% 12ma growth rate in 2019. As a result, Turkish banks' loan/deposit ratio has fallen from a peak of around 111% in 2017/18 to 91.8% by end-2019. This is the lowest bank leverage rate since 2012.

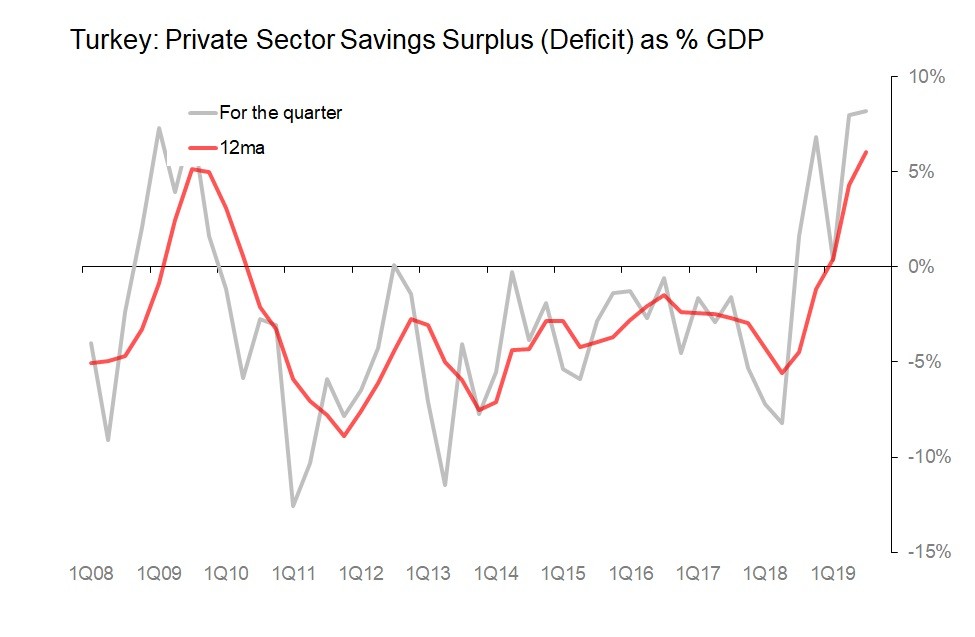

This deleveraging is also expressed and generated by very sharp turnaround in private sector financial behaviour, in which a net cashflow drain equivalent to 5.6% of GDP at its nadir in the 12m to June 2018 has been replaced by net positive cashflow equivalent to 6% of GDP in the 12m to September 2019. This positive cashflow is, of course, a positive flow of cash from the private sector to the financial sector which, by definition, can only be spent on buying public sector assets (ie govt bonds), or foreign assets (ie, paying down foreign liabilities).

One important source of cashflow recovery was not only a stand-still in investment spending, but also a quite dramatic inventory-dump which took place between 4Q18 and 3Q19. This inventory-dump cut into GDP growth, cutting nominal growth to 14.1% in the 12m to September 2019, although final spending on domestic product was maintained at 18.1% during the same period. Meanwhile, the stand-still in investment spending cut estimated capital stock growth to 13.5% yoy. Taken together, this allowed the return on capital directional indicator to recovery smartly from the nadir of 2017-2018.

So we now have a situation where:

the private sector is generating positive cashflows,

the banking system has deleveraged to some extent and repaid substantial foreign liabilities,

the decline in the return on capital has been reversed, and

a large inventory clear-out has been made.

In these circumstances, for the time being one can park doubts and qualms about the underlying policy-set, and underlying policy-tendencies which remain relatively unreconstructed. Because for the next few quarters, Turkey's financial markets are likely to be benefiting from a classic emerging-market post-crisis recovery.