Dec 30•13 min read

2020 : Manzikert

Empires usually don't collapse. Like great trees, they decay from within and eventually succumb to their fate.

In 1071, probably nobody that mattered in Constantinople thought that the defeat in Manzikert, towards the eastern borders of the vast and ancient Byzantine empire had sounded its death-knell. That death wouldn't fully and finally arrive until nearly 300 years later, when in 1453 Constantinople fell to Mehmed II after a 53 day siege. It was that defeat which finally lowered the curtain on a Roman Empire which had endured one way or another for approximately 1,500 years.

Nevertheless, historians are unanimous: the battle of Manzikert was 'the greatest disaster suffered by the Empire of Byzantium in the seven and a half centuries of its existence'. Even the subsequent arrival of Alexius Comnenus as the model of heroic leadership could undo the damage done by the battle. Byzantium lost Anatolia to the Seljuk Turks, and with it the tax and manpower resources necessary for its long-term viability. With it went the Byzantine Empire, the Roman Empire, and the vision of united Western Christendom ultimately centred on, and protected by, Constantinople.

Although 1071 isn't a date tripping off anyone's tongue, it should be: it is among the most disastrous in the history of Western civilization. Manzikert was the moment is began to fail.

The sobering fact is that the battle of Manzikert was fought unnecessarily and, in fact, only by accident. It was lost mainly because of treacherous defections engineered by political divisions in Constantinople. The Seluk victor, Sultan Alp Arslan was a reluctant foe and immediately offered mitigation of the defeat, and, indeed, a resumption of Byzantine rule. That opportunity for immediate recovery was dashed by Byzantine imperial political divisions. In short, Manzikert was fought by accident, lost through treachery, and the consequences amplified by political opportunism.

Alp Arslan never envisaged fighting the Empire at Manzikert: until very recently the Seljuks were little more than a nomadic tribe from Central Asia 'leading a life a brigandage: fighting with neighbouring tribes, pillaging and plundering wherever the opportunity arose.' By the the 1050s opportunity had knocked, and they had established a protectorate over the moribund Abbasid Caliphate centred in Baghdad. This had never been their ultimate objective - still less had they considered taking on the Empire. 'The idea of annihilating Byzantium would have struck the Seljuk Sultans as completely unrealistic, even ridiculous'. Rather, the Sultan had his eyes on taking down Fatimid Egypt, who he reviled as Shi'ite heretics, and with whom he believed a to-the-death struggle was inevitable.

Still, the intermediate problem was Armenia, which the Empire had done its best to alienate, despite being a protectorate of major strategic importance, and which had fallen to the Seljuks.

A new Emperor, Romanus Diogenes, embodied the Anatolian military caste and was fully aware of the gravity of the threat presented by a Seljuk-dominated Armenia. By early 1070, a truce between the Empire and Alp was collapsing in the face of habitual raiding by Turkomen, who Alp was unable to control, and which he disclaimed all responsibility for. So Romanus assembled an enormous army - 60,000-70,000 - and set out. But whilst Romanus was marching across Anatolia to meet the Seljuks, Alp was marching in a completely different direction - the Seljuks were off finally to settle the Fatimid's hash.

Romanus proposed a new truce and swap of various territories (including Manzikert), but trust was in short supply, and seeing the vast imperial army coming, Alp abandoned his Fatimid ambitions, turned round, and headed for home fast (indeed, in his haste, the Euphrates claimed many of his horses and mules). Romanus caught up with him outside Manzikert.

Alp's army was almost certainly heavily outnumbered. But not for long. Romanus was abandoned first by roughly half his army, seemingly betrayed by a general controlled by his enemies in Constantinople; then some of his Turkic mercenaries also fell away. Nevertheless, after a day and a fraught night of skirmishing, Alp offered another truce. After all, the Seljuks hadn't wanted to fight the Empire, and as raiders, they were none too keen on pitched battles. Romanus spurned the offer, and 'battle was joined' again the next day. Or rather, it wasn't, since in a pattern absolutely typical through the ages, as the Empire's army advanced, the Seljuks retreated in an enveloping crescent avoiding contact until the Empire's army was outflanked on both sides. At this point, Romanus' rearguard abandoned him, led by another general controlled by his enemies in Constantinople spreading the word that all was lost. And after that it was: the Sultan pounced for his victory.

The Sultan was an exceptionally generous victor: the captured emperor was made to kiss the ground as Alp placed his foot on his neck. But after that humiliation, he was treated with all courtesy, remaining as Sultan's guest, before negotiating a ransom only around 15% of that originally asked, and agreeing a treaty swapping territories. Romanus was then sent back to Constantinople as emperor, with an escort of two Emirs and a hundred Mamelukes.

It could have been worse. So the fractured imperial politics of Constantinople made sure it was. Romanus was deposed and blinded, and in his place a favourite of the imperial bureaucracy - and a headliner for the faction who had betrayed Romanus at Manzikert - was installed. With Romanus gone, the treaty he signed with the Sultan was a dead letter, and Alp once again had to abandon his dreams of war with the Fatimids. It took a full two years after Manzikert for the Sultan to conclude that, in the circumstances, he might as well move in to Analtolia. By 1080, the Seljuks were in control of approximately 30,000 square miles of Eastern Anatolia, renamed as the Sultanate of Rum.

This is how the Roman/Byzantine Empire met its end.

I hope you enjoyed this history lesson. I wrote it because 2020 reminded me that even the most robust civilization can unintentionally inflict on itself wounds of a sort which turn out to be, eventually, terminal, even though they seem survivable at first glance. Manzikert was a battle offered against an unwilling foe, lost through treachery, with a victory gained almost unwillingly, with a victor almost anxious not to grasp the reward. The outcome was still lethal.

What, then, has been lost in 2020 which in the long term might seem irreparable, or, at the very least, recoverable only with a concerted and sustained political effort which seems unlikely.

Developed country perspective on mortality. Covid-19 is a nasty disease which has spread around the world, killing millions of people, overwhelmingly either the elderly or those vulnerable because of co-morbidities. In global terms, it is not unprecedented - TB and lack of plumbing kill more every year. But the reaction to it in the developed world has generally been hysterical. The wilder conspiracy theorists attribute its arrival to . . . . oh, who really cares what these maniacs babble on about? But the response from those in positions of power has been almost equally as hysterical, with massive swathes of the developed economies forced into submission in response. As the year ends, it is plain - as indeed it was at the beginning of this year - that the virus stands zero chance of even medium-term survival against mankind's technical ability to wage war against it. As I write, the world's pharma companies are queuing up to see which can eradicate it quickest. The little bugger will have to move fast if it is to stay in the fight.

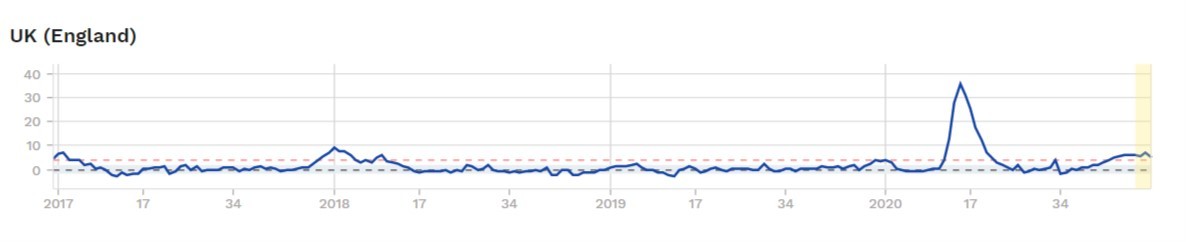

Meanwhile, the fact is that, as 2020 comes to an end, with much of Europe's economy locked down, its achievements as a killer are not panic-inspiringly impressive. The European Mortality Monitoring organization (Euromomo - https://www.euromomo.eu/graphs-and-maps/) keeps the score, and compares weekly deaths to the usual five-year pattern, to establish the 'excess deaths' suffered. The UK is popularly thought to have suffered more than most: here's how its 2020 mortality has differed from the normal, with the data running to week 50. Bear in mind that right now most of the UK's economy is almost fully locked down.

It may turn out that the most serious damage down by Covid-19 is to the 'soft power' the West has enjoyed. Covid has revealed the West's governments to be both pusillanimous and surprisingly incompetent. Who will look to these governments, or even these societies, as a model to be emulated?

The blase abandonment of monetary and fiscal responsibility is a related self-inflicted wound. As with Manzikert, it is not the loss itself that really matters so much as what it signals for the future. We forget, for example, that the US financed the Second World War largely out of taxes, and that the part it could not finance out of taxes, it financed out of war-bonds which it took great care to ensure ended up in non-bank hands (indeed, most were 'restricted). But in the case of Covid-19 - a threat which in all honestly does not compare with the armed might of the Axis Powers - the response has been entirely debt-financed, with as much of that debt as possible ending up not even in the banking system, but on the balance sheets of the major central banks.

We the electorate watch, and discover that there are, apparently, no restraints on governments' ability to raise debts, and no inflationary consequences if the central banks prints money to fit. If that's the lesson we've learned in 2020, pity the finance minister who decides the fiscal deficit must be reined in, pity the central bank governor who decides there must be a limit to the expansion of its balance sheet. Unless it turns out that - contrary to universal previous experience - there are no limits to monetary and fiscal irresponsibility, a time will come when these painful rediscoveries will have to be made.

What are the chances of our governments' engineering a soft landing?

In 2020 we also have to consider the state within Constantinople, or Washington. Writing as a British former journalist, the situation is genuinely distressing. Where to start? In the long run, I am most distressed, most alarmed by what has happened to US journalism. In 2020, it seemed happy to make the dire segue from mere disinterest in the truth, to a pernicious active partisanship. As a former journalist I find it, for example, absolutely incomprehensible that the US media was not only not interested in what seems frankly indisputable evidence of big-money corruption in the Biden family, but was actively and enthusiastically complicit in successful attempts to suppress the story. That Big Tech in the form of Facebook, Youtube, Twitter and even Google joined in attempts to keep the story from the electorate is, if less surprising, yet more sinister. I take the Biden corruption case not because it is necessarily the worst, but because the problem is so obvious, so very difficult to pretend not to see).

The upshot is that, in the world's most important polity, we can and should expect to be governed more often by partisan lies than unwanted truths, and that those who seek to tell the truth are more likely to be punished and suppressed than rewarded. Whatever you want to call it, this is not land of democracy and liberty I thought I knew, and knew I loved.

Jettisoning the primacy of truth is a hell of a price to pay for getting rid of Orange Man.

It also has this consequence: what's being burned up here is the 'soft power' the US uses to assemble coalitions to address issues thought of as important to 'the West'. If every dossier is treated as 'dodgy', the soft power is lost. All that remains is imperium.

Is it possible that US media will recover itself? It seems possible, but very unlikely.

Persecutions, Creeps and the New Religion. We've not yet got to the state where those wearing glasses are sent down to learn from the peasantry, but we're well past the point where lives, careers and posthumous reputations are ruined by gleeful persecutors doing what religious bigots have done throughout history. Plenty of people have learned the knack of writing the sort of self-criticisms demanded by Mao's Red Guards, in the (often vain) hope of saving themselves as viable in the public realm. One of the more astonishing combinations of stupidity, nastiness and abuse of position came with the attempt by the British Library to censure the British poet Ted Hughes (for my money, the finest English poet since Shakespeare) for his connections to the slave trade. Those connections? Oh, some relation born in 1592 who had connections to colonialism via the London Virginia Company. 1592! And what did Ted Hughes' white privilege buy him? a childhood in a two-up-and-two-down semi in a grim small town in West Yorkshire.

What empowered the British Library to pursue Hughes' absurdly distant ancestor down the ages (and as far as I know, the creep involved is still employed, still deemed employable)? The death of George Floyd in Minneapolis, US. Go figure.

We have come to regard certain episodes in world history as outbreaks of madness. In no particular order: Byzantium's iconoclasm; Munster's Anabaptist outbreak; of Savonarola's bonfires of the vanities; the Salem witch trials; McCarthyism; the Cultural Revolution; Pol Pot's Year Zero. I have no difficulty in believing that in Western societies, as elsewhere, the colour of your skin affects your life chances, as do many other factors over which you have no control. But the response to that favoured in 2020, seemingly not only by the mob, but also by much of the corporate world, seems far more likely to eradicate and denounce Western civilization than to eradicate racism. Frankly, during 2020, that had seemed on occasion to be the desired point. Frenzied self-abasement doesn't usually characterize a healthy society.

Surveillance & Alien Invasion. Finally, it is worth asking how many of the self-inflicted wounds of 2020 were facilitated by the unchecked rise of a surveillance capitalism and the attention economy which has a massive commercial incentive in fostering division. Would the Covid-19 pandemic have shut entire economies, would it have ushered in the abandonment of monetary and fiscal plausibility, would George Floyd's death have resulted in British Library creeps castigating Ted Hughes' very distant relative, would US media have given up interest in the truth, without the revealed power of Facebook, Twitter et al.

I no longer view Facebook, Twitter, Youtube etc as being the playthings of new Tech Overlords, to whom we are in feudal subjection. I severely doubt whether Zuckerberg can control Facebook, or Jack Dorsey can control Twitter. Rather, they have a life of their own: they are our own alien invasion. What will these alien creatures have in store for us in 2021 and after? And will the West survive their attentions? Or will 2020 be our Manzikert?