Nov 14•5 min read

Chaos, Confidence, Money and Trade

The final quarter of 2020 may seem, objectively, to be an unusually chaotic and even threatening time, as the world attempts to avoid or navigate a second wave of Covid-19, whilst potentially decade-defining political change unfolds in the US and Europe (via Brexit). Conditions like these ought to be undermining confidence, particularly in the US and Europe, but also in their Asian trading partners.

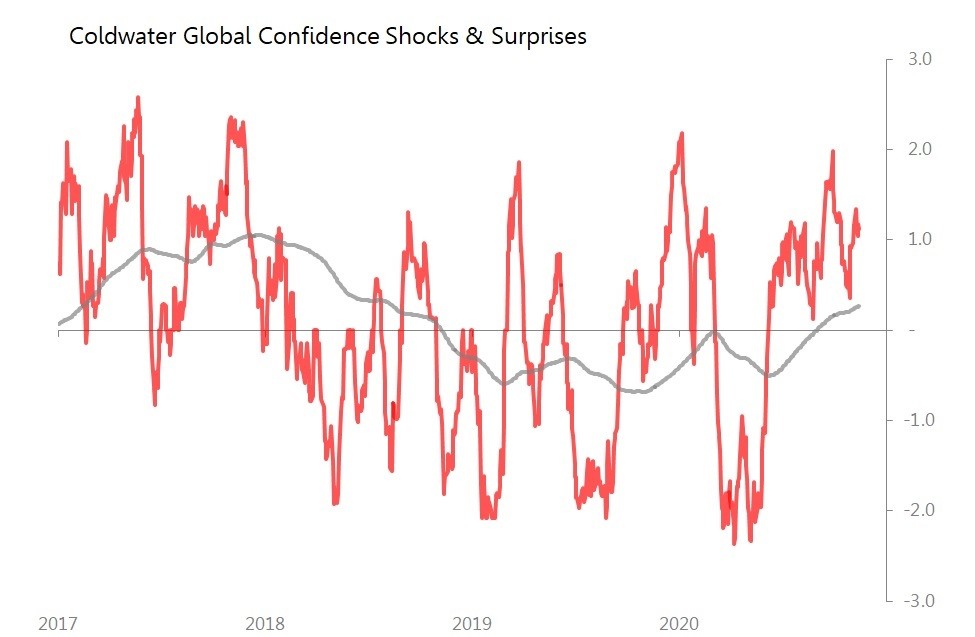

But this is not what is happening: rather, seemingly in defiance of the newsflow, economic confidence indicators continue to be broadly positive. In fact, the Coldwater Global Confidence shocks & surprises index has been continuously positive since early June. On a 12m basis, it is now at its most bullish since August 2018, and is still rising.

This is very different to the collapse in confidence which accompanied the first wave of the pandemic, when confidence indicators collapsed dramatically around the end of February/beginning of March. This collapse happened almost simultaneously as the threat from Covid-19 morphed from localised epidemic to full-blown pandemic. To recall the timeline: Covid-19 hit the headlines in China in late January, spreading to S Korea in late February, before spreading to Japan, Italy and Spain in early March, then on to France, UK and US by late March. By that time, confidence was already shot.

The second wave has had plenty of time to get to work on confidence, since it has been building gradually since August in Asia, and since September in Europe, whilst in the US the first wave has never really broken. But not only is Coldwater's confidence index still perky, there is no sign even in the latest data that disease and politics are having the sort of dramatic impact previously endured. This week, for example, we had positive confidence surprises from:

Japan's Economy Watchers - Current Situation;

Thailand consumer confidence;

Australia NAB Business confidence;

Eurozone Sentix Investor confidence;

UK RICS House Prices index.

And we had confidence shocks only from the Zew index for Eurozone expectations, and in the US, the Uni of Michigan consumer sentiment index and the IBD/TIPP economic confidence index, both of which fell sharply. There were neutral readings from Japan's economy watchers outlook index, Australia NAB business conditions index, Germany's Zew index, France Bank of France manufacturing outlook, and US small business optimism index.

This is almost insouciance, and it raises the question: 'Why?'

One possible answer is that the combination of monetary and fiscal stimulus put in place during the first wave was so overwhelming that it is working, producing an unexpectedly strong recovery in global trading patterns.

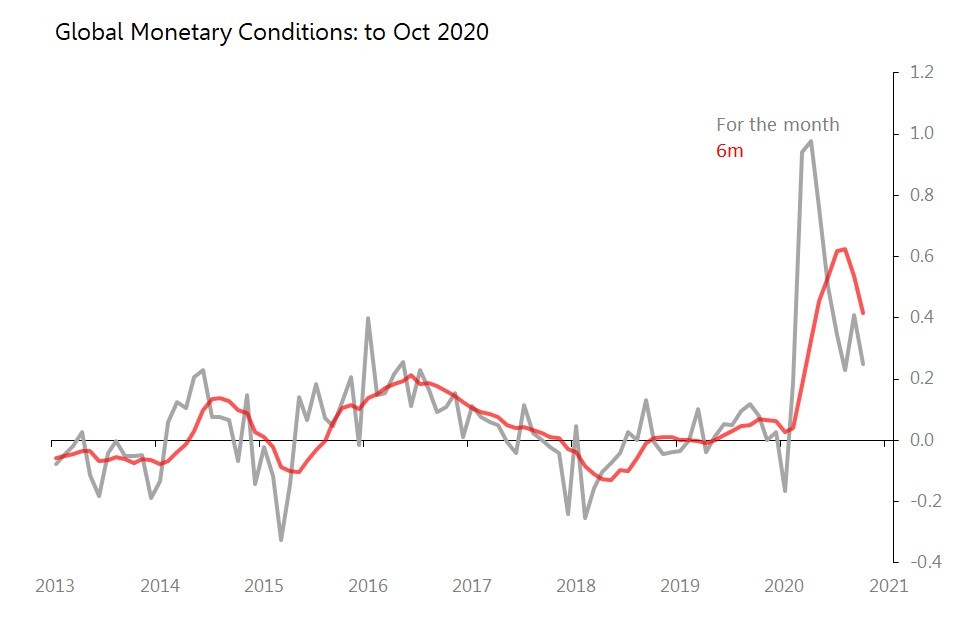

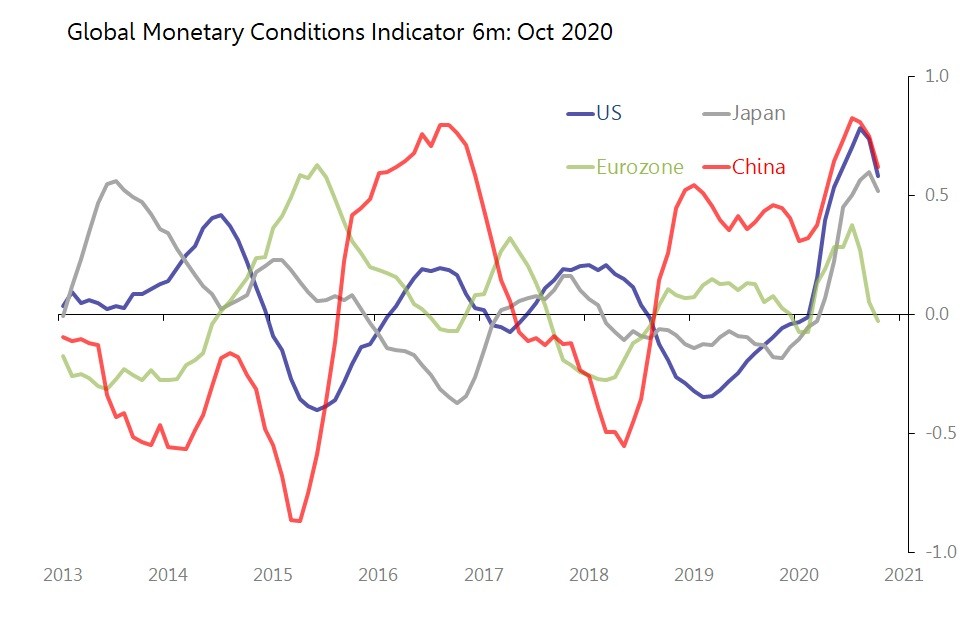

The monetary response to the first wave was colossal, and even though it is not currently being repeated, its impact is still being felt in the world economy. For each major economy I track monetary conditions by measuring at: i) growth of monetary aggregate; ii) changes in real bond yields; iii) changes in the shape of the yield curve; and iv) change in the value of currencies vs the SDR (direction and volatility). The global monetary conditions index is a GDP-weighted aggregate of indicators for the US, Eurozone, China and Japan. It shows that although the initial monetary frenzy of the first wave is not being repeated, conditions remain historically extremely accommodating.

This accommodation is (still) being led by the US and China, with Japan's impetus slightly fading, whilst the Eurozone is lagging. During October, the US Fed expanded its balance sheet by $109bn, which mainly represented a typical seasonal fluctuation (it was 0.2SDs above trend) and compared to the nearly $1tr a month averaged between March and May. In Japan, BOJ expanded by Yn8.2tr, a noticeable slowdown from the Yn 16.3tr a month averaged between March and August. In Europe, the ECB added only Eu71bn, also a step-change down from the Eu400bn a month averaged between March and June.

Despite this recent moderation, the charts show that the extraordinary monetary accommodation of the first half of the year has been moderated, not reversed (even in the Eurozone). In the absence of any monetary reversal, one should expect that initial expansion gradually to make an impact on the world economy. This is particularly true when the US and Europe remain deliberately ham-strung in supply by government-mandated lockdowns, and also cyclically short of inventory.

The result is, perhaps counter-intuitively, that economies in Northeast Asia which can supply the world economy are experiencing an unusually strong upturn in demand for their exports. This strength in export demand continued into October, when in dollar terms NE Asia's exports rose 6.6% yoy (includes estimate for Japan modelled from 20-day results), and with a monthly movt 0.3SDs above historic seasonal trends. As the chart shows, both the yoy growth, and the 6m gain above historic seasonal trends are among the strongest seen for approximately two years (or more, for momentum).

In October, it seems that strength was no longer confined to China:

China's exports rose 11.3% yoy, with the monthly movt 0.3SDs above historic seasonal trends

Taiwan's exports rose 11.2% yoy , with a monthly movt 0.3SDs above trend

Japan's exports fell an estimated 2.3% yoy,with a monthly movt 0.4SDs above trend (these estimates are made using the 20-day trade data, which showed exports down 2% yoy in dollar terms)

Only S Korea continued to suffer, with exports down 3.7% yoy and 0.8SDs below historic trends.

The conclusion seems quite simple: confidence is surviving because the stimulus offered during the first wave of the pandemic was so huge that it muted the immediate impact and has fostered an upturn in global trade which, in turn, continues to bolster economic confidence.