Feb 26•4 min read

Hong Kong 2019: The Siege Before Coronavirus

You'd have thought things could not get much worse for Hong Kong than what it experienced in 2019, when unresolved political antipathies brought the SAR to a functional halt on a fairly regular basis and undermined the authority of the government in spectacular fashion. But then January 2020 brought coronavirus.

So what sort of shape is Hong Kong in to cope with this new round of pressures?

The 4Q GDP result is bad enough: GDP fell 2.9% yoy, as private consumption fell 2.9% and gross fixed capital formation dropped 16.7%, with private investment down 20.4% and public sector down 2.2%. As a result, domestic demand dropped 4.9% yoy. However, the statistical misery was mitigated by net exports, which added back 1.3% to yoy growth thanks to the unexpected arrival of a goods trade surplus which offset a collapse in the services surplus, and a possibly involuntary accumulation of inventories which added back a further 62bps to yoy growth.

So far so bad. However, Hong Kong is nothing if not agile in its response to even commanding economic difficulties, and there were two surprising signs of adaptation visible in the 4Q data.

First, despite the fall in nominal GDP (down 1.2% yoy in 4Q), investment in machinery and equipment fell so hard (down 27.2% yoy) that by my calculation Hong Kong's capital stock (ex-construction) fell by 1.5%. This in turn, allowed my return on capital directional indicator (ROCDI) actually to inch upwards despite everything. Now the combination of stable to rising ROCDI and sharply falling capital stock may not be exciting for profits in the short term, but it does lay the foundations for a cyclical recovery. Or rather, it would, had not coronavirus been added to the mix.

The second surprising factor is the relative resilience of Hong Kong's ability to price its services and consequently to limit the decline in its services terms of trade - the crucial factor underpinning Hong Kong's entire pricing structure. One would have expected both to come under severe pressure. However, the overall price of Hong Kong's services exports actually rose 0.6% qoq in 4Q, resulting in a fall of only 1% yoy in pricing. This is, I think, remarkable, given that total services exports fell a nominal 25.4% yoy, with travel revenues down 54.1% and transport services down 17.9%. To put these falls in context: in 2003, the year of SARS, Hong Kong's travel revenues fell only 4.4%, whilst in 2019 they fell 21.3%.

These losses were mitigated by falls of only 3.3% yoy in financial services and 3.1% in business services.

Overall, the determination to preserve pricing in these dreadful commercial circumstances is surprising. Although the services terms of trade deteriorated 2.2% qoq and 1.6% yoy this was a retreat from record highs in 2018, and maintains Hong Kong's terms of trade still towards the higher end of the level it has maintained since 2012. Given that it is Hong Kong's ability to price its services internationally that underpins its property market valuations, this is both surprising and welcome.

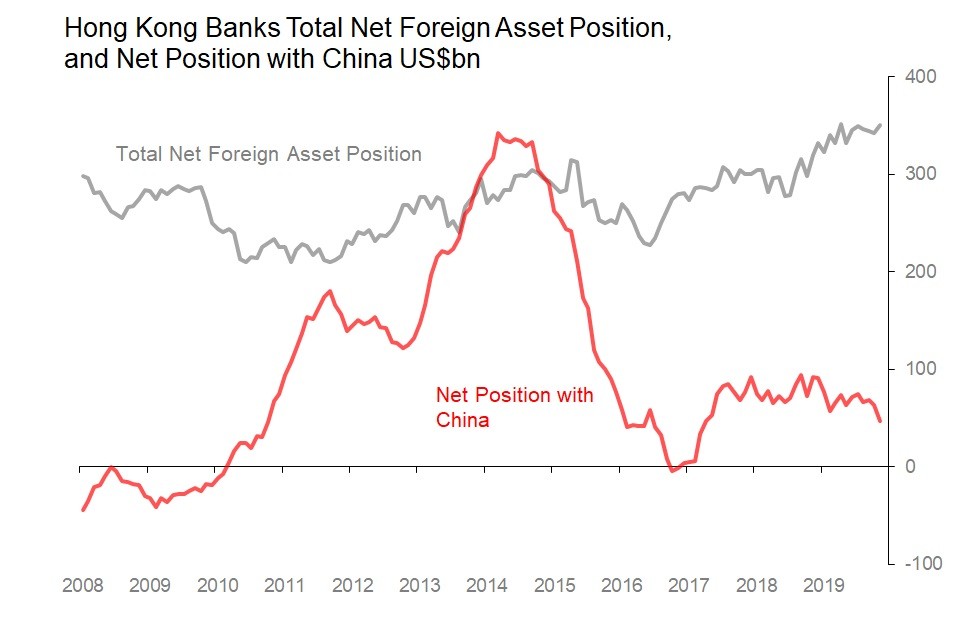

There is another consequence of this mixture of agility, determination and financial conservatism in the face of adversity, and that is that Hong Kong's banking system emerges from the mess of 2019 increasingly well insulated both from any expected souring of the international funding environment, but also with reduced direct exposure to China-risk. For the total picture, by November 2019 Hong Kong's banking system had net external assets of US$350bn, up US$31bn yoy, and almost a record high. Meanwhile, its net asset holdings with mainland creditors was down US$40bn yoy at US$123bn, the lowest since the beginning of 2017.

No China-based assets can be expected to escape coronavirus without damage, of course, and it is very unlikely the international funding environment generally will not be impaired for some time. However, it appears that the dreadful political disruptions of 2019 have at least bequeathed Hong Kong a financial system which, by chance, appears to be well prepared to weather the coronavirus storm.