Mar 06•11 min read

Healthcare and Wealthcare

Probably no two recessions are exactly the same. However, the general idea is that they arrive when a degree of malinvestment has evolved and been recognized by markets, with the subsequent recession being an unpleasant process in which resources are, ultimately, redeployed to open the way for a new phase and pattern of growth. Now, the exact interpretation of this general idea varies according to the structure of the economy involved. So, for example, in a manufacturing-dominated economy, disequilibriums between the supply and demand of goods do much of the work. Typically an unexpected state of undersupply generates inflation in prices and (temporarily) profits, which in turn attracts the malinvestment which gets bled out through the deflation of the subsequent bust. Paying attention to inventory movements and wholesale markets not only allows one to monitor these disequilibriums, but inventories themselves can act as 'accelerators' of the whole process.

In service-driven economies, the recession-threatening disequilibria are less obvious and more difficult to track. This is partly because inventory movements play a peripheral role in services production, and partly because service industries tend to be less capital intensive and therefore inherently more flexible. Rather, they tend to emerge in response to demand shocks, and are more likely to develop directly but slowly as weakening labour markets feed back into the initial demand shock.

One consequence is to raise the perceived value of a monetary policy response to the threat of a service-dominated recession. At its crudest, monetary policy is used to generate a 'wealth effect' which answers the initial demand shock. In the short, medium and long term the balance-sheet implications of such responses can be ignored by policymakers. In the very long term, the jury is still out, although, as we shall see, it is easy to rain down jeremiads of condemnation insisting that the malinvestments built up over decades must be so massive they can only end in utter disaster.

Apologies for the long introduction. The key point I want to make is that although no two recessions are exactly the same, economic thought and actual policy responses take it for granted that recessions are typically a result of endogenous factors built into the nature of the business cycle and of growth itself. The mechanics and dynamics of a recession are recognitions of something that has gone wrong in the process of growth itself, so any competent response should not seek unreasonably to frustrate the process of rectification.

In other words, Acts of God are not involved.

But the coronavirus certainly qualifies as an Act of God. Indeed, in earlier centuries, a visitation of plague would explicitly be explained as the justice visited upon an iniquitous people by a wrathful deity.

Worryingly, right now, the more excitable economic and financial commentary has donned the full sackcloth and ashes, and invites us to consider, and lament, the End of Economic Days. And indeed, it's easy enough to condemn the conduct of US fiscal and monetary policies of the last 30 years. Any decent philippic would damn the build-up of federal debt, the distortion of asset pricing and what it has done to corporate behaviour, the erosion of long-term useful financial and economic behaviours, and the gross widening of inequalities of income and, particularly wealth. Indeed, who wouldn't want to get on board with such a critique? And from there it is but a short rhetorical step towards a full prophetic jeremiad heralding the Great Rectifying Uber-Crash waiting in the wings.

Now we have what feels like a genuine Act of God in the coronavirus to kick things off. So is this it?

Let's look: specifically, what sort of condition the US economy is in as the Act of God begins to pummel it.

One starting point is to acknowledge that even pre-coronavirus, a sharp slowdown, probably in the manufacturing sector, looked likely in 2021, although it was uncertain whether this would lead to a full blown recession. The key metrics suggesting this are the sharp slowdown in heavy truck sales seen since October 2019 - invariably a precursor of a slowdown, and usually recession, and the inversion in the 2yr/3m yield curve which opened up around this time last year and persisted until this week's rate cut. (An inversion at the shorter end of the curve is much more persuasive than at the long-end.)

insert /gd/heavy trucks.jpg

However, there were a number of factors which suggested that 2021 would see only a repeat of the 2016 un-noticed industrial recession rather than an economy-wide phenomenon. In particular, the strength of labour markets remains a bulwark against full recession. And this is not merely the overall headline strength (February's data showing ADP private sector payrolls up 183k, full non-farm payrolls up 273k), but the structure of who is doing the hiring. In particular, there is no sign of the waning demand from large or medium sized companies which has preceded previous recessions: rather, if anything smaller companies are finding harder to attract and retain staff.

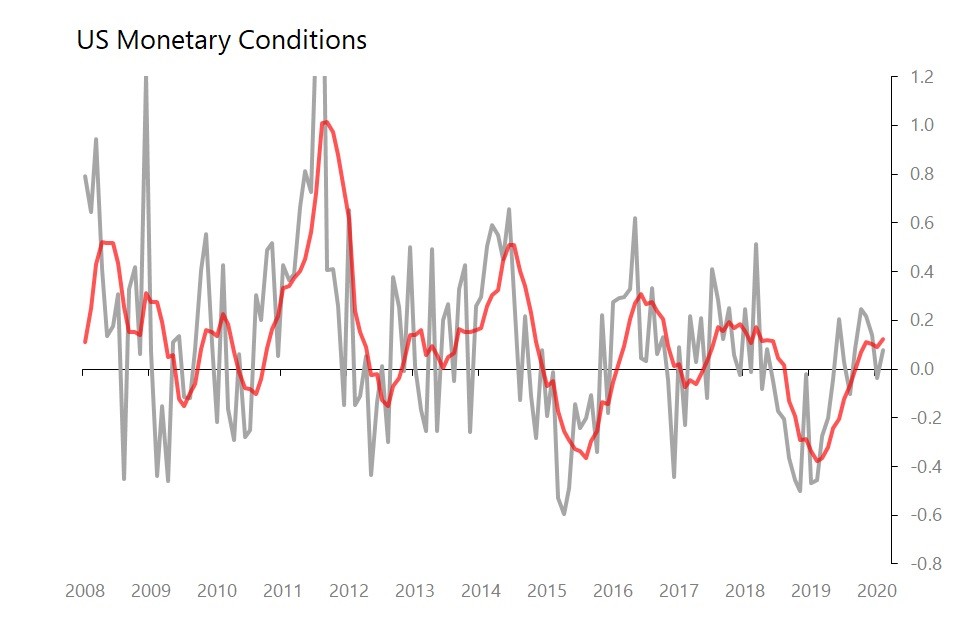

In addition, it seemed that the loosening of monetary conditions achieved in the latter part of 2019, which reversed the tightening of the previous 18 months, is well timed to moderate the industrial slowdown expected in 2021. (My monetary conditions indicator tracks monetary growth, movements of the dollar/SDR, real 10yr yields and the shape of the 10yr/3m yield curve.)

us/us monetary conditions.jpg

These possibly subcyclical fluctuations make an uneasy background, but by themselves surely do not herald the End of Days scenarios. For that, we have to consider the state of corporate and household balance sheets as the Act of God puts them under unexpected pressure.

Corporate Balance Sheets

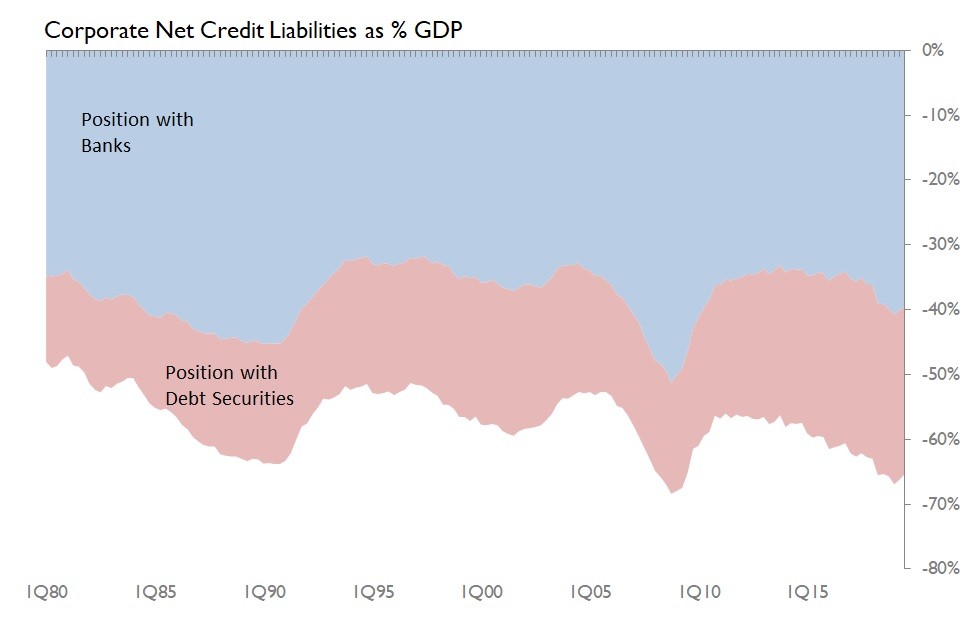

How vulnerable are corporate finances? Well, the US flow of fund tables tell us that by 3Q19 gross corporate debt had risen to $22.04 trillion, up 6% yoy, and equivalent to 102.3% of GDP. That's within spitting distance of the record 106% of GDP seen in 1Q09, and consequently clearly a flashing light.

But that is not the end of the story. The net corporate position is milder, with a net liability to credit markets of $5.57 trillion, and a net liability to banks of $8.5trillion. Taken together, that comes to a net liability of $14.06 trillion, equivalent to 65.3% of GDP. Now that is also within spitting distance of the 2008 record of 68.4% of GDP. Once again, there is little for one's comfort there.

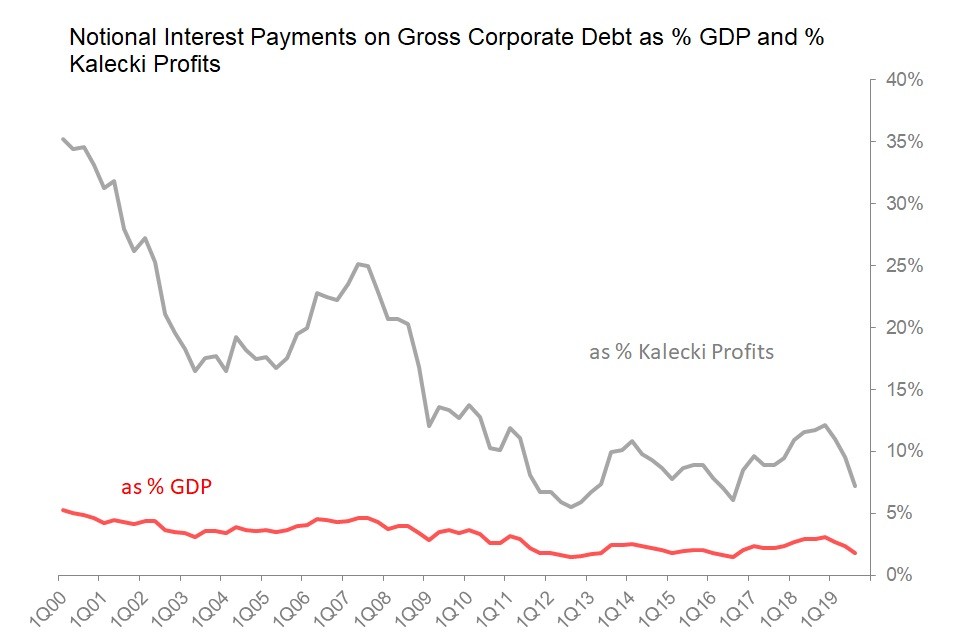

The severity of the burden of servicing those net liabilities will depend principally on two other factors: what's happening to interest rates, and what is happening to the profits from which the interest is to be repaid. To recap:

back at the end of 2008, 10yr Treasuries were yielding 3.2% (and falling); during 3Q19, on the other hand, yield were at 1.8% (and falling).

In 2008, Kalecki profits had risen to 20.2% of GDP; by 3Q19, Kalecki profits were equivalent to 25.3% of GDP.

As a result, the burden of servicing gross corporate liabilities is very much lower now than it was in 2008. Assuming the interest payable on the gross debt is determined by the 10yr Treasury yield (which is obviously incorrect, but it's reasonable to assume the error is normalized), then:

in 2008, interest payments would be equivalent to 3.4% of GDP and 17% of Kalecki profits;

in 2019, interest payments would be equivalent to 1.8% of GDP and 7% of Kalecki profits.

Moral: Despite taking on historically high levels of net debts, it would take a significant tightening in interest rates to deliver major corporate debt distress. The philippics and jeremiads are not wrong about the build-up of corporate debt, but whilst politicians and central bankers continue to underwrite this behaviour, it will continue. Life isn't fair.

However, it seems absolutely certain that the growth of both Kalecki profits (up 4.9% in 2019) and of nominal GDP will be slashed by the impact of the coronavirus - although in both cases the extent of the damage will depend on the degree of fiscal mitigation is allowed to offset the inevitable fall in net investment spending and household dissaving. (Note, incidentally, how in these circumstances, the fiscal response is probably going to matter more than the monetary policy response.)

We must expect the burden of corporate interest payments relative to both GDP and profits to rise, but in both cases, the starting position is relatively encouraging, and it seems unlikely that the burden of servicing corporate balance sheets will approach the levels sustained between 2000 and 2007.

Unfortunately, that level of protection is not the final word on the financial fragility bred into the US economy from the decades of monetary policy tacitly underwriting financial asset prices. The problem is that although Kalecki profits have continued to rise, equity prices have risen faster. As a result, the ratio of Kalecki profits to the SPX index, for example, started 2020 at an all-time high. There is, then, plainly, a sharp vulnerability of asset prices to any fall in Kalecki profits - a fall which the Act of God makes all-but inevitable. That vulnerability is not necessarily answered simply by a fall in interest rates. In fact, this vulnerability is precisely the disequilibrium which has been fostered by monetary policies over decades.

Household balance sheets

At this point, we need to look at the structure of household balance sheets, to think about their exposure to a fall in financial asset prices. The place to look is, of course, the quarterly flow of funds tables, which give the most detailed breakdown of household balance sheets available. And at first glance these are relatively encouraging: at end 3Q19, the US household sector had a net holding of $74.6 trillion of financial assets. (I stress this is a net number, including all mortgage and consumer debt). More, households had a net positive position with credit markets (ie, with banks and debt paper markets), amounting to $832 billion. As the chart shows, this net positive balance with banks and credit markets is in dramatic contrast to the $4.5 trillion in net debts held at the nadir of 3Q07. The belief that US growth has been underwritten purely by an increase in household debt is, emphatically, not supported by the available data. Taken as a whole, then, the vulnerability of the household sector looks relatively unthreatening.

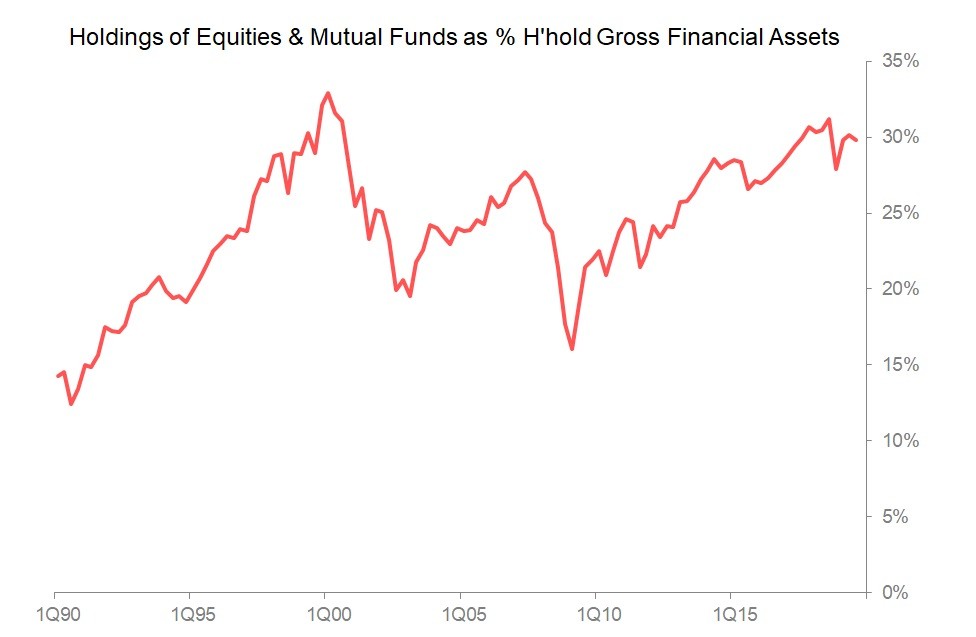

This, however, is not quite the end of the story, for two reasons. First, what the macro data does not tell us whether wealth concentration means the aggregate position is hiding significant and widespread financial vulnerability. Second, the build-up of net financial assets includes large-scale exposure to the fall in asset prices which seems inevitable given the pressure the Act of God will put on Kalecki profits. The latest data shows households held $18.04 trillion in equities and a further $9.07 trillion in mutual funds at end-Sept 2019, which was equivalent to just under 30% of gross financial assets, and 36.3% of net financial assets.

To put it in some context, it would take a fall in share prices of just 3% to effectively wipe out the household sector's net positive position with banks and credit markets. That $832bn buffer suddenly doesn't seem so reassuring.

What do we conclude? Although balance sheets for both the corporate and household sectors looks considerably more manageable than (particularly) in 2007/08, the vulnerability they share is the exposure to asset prices at a time when a) asset prices are at historic highs relative to Kalecki profits, and b) Kalecki profits are almost inevitably being sharply hit by the Act of God. In these circumstances, I would suggest the following:

First, monetary policy alone is unlikely to be effective: what matters now is the ability to minimise the fall in profits. Coronavirus is a real challenge to American's expensive system of socialized wealthcare, and it alone should not be expected to cope with it.

Second, fiscal policy is the key available instrument which can minimise the fall in profits. (Why? Because Kalecki profits are determined by i) net investment spending; ii) net household dissaving; iii) net government dissaving and iv) movements in net exports. Of those, i) and ii) are going to come under pressure, and the fate of iv) is unpredictable. If profits are to be sustained, therefore, it will be at the cost of a widening fiscal deficit).

Third, for the time being, one should suspend the impulse that non-interference in the cycle is the best policy, because what we are dealing with here is not something endogenous to the pattern of US growth, rather it is an Act of God. Normal virtue can be attempted in the aftermath.