Dec 27•7 min read

2019: Funk, Lies & Displacement Activity

It is perhaps a bit aggressive to acknowledge it, but in economic terms 2019 was a year of funk, lies and displacement activity.

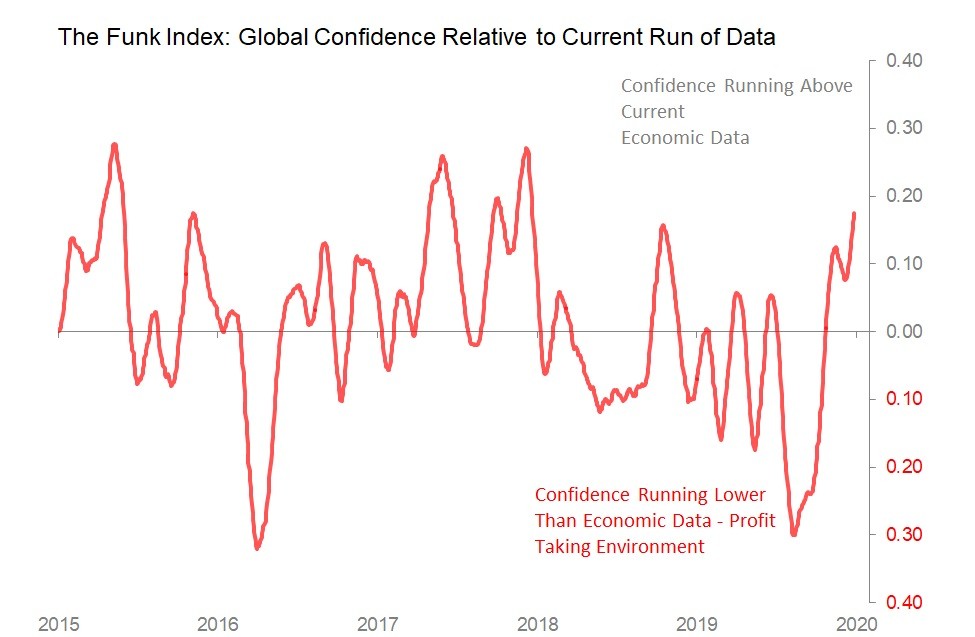

Let's start with Funk. As part of my daily patrol of global economic data, I separate out confidence survey data from the 'hard' data reporting trade, industry and demand activity, constructing 'shocks & surprises' indexes for both. Using these, I construct a 'funk index' which tracks the degree to which movements in confidence indicators are justified by current movements in the 'hard' data. When confidence is sinking below what is justified by the hard data (regardless of whether the hard data is positive or negative), I interpret the difference as a degree of Funk. And in that sense, 2019 saw the deepest and most sustained divorce between fear and reality that we've seen in recent years.

Essentially the world has been in an economic funk, with few exceptions, since March 2018 and has only convincingly come out of it the last two months of 2019. Still, within this period of general gloom, the deep funk climax came this year, and lasted from July 2019 to late-October.

Now Let's Think About Lies. What lay behind this deep funk? There were some popular explanations which, were I feeling charitable (as I ought at this time of year), I would allow to be merely failures of imagination and ignorance. In particular, throughout the year, it was a rare downturn in developed world data anywhere that wasn't, by reflex, attributed to the malign impact of the pressure put on US-China trade and investment relations by President Trump. (Although in Europe, Brexit was also pressed into services as a co-culprit.) This single-factor explanation is attractive to many because, by identifying a specific anomalous exogenous factor, it allowed the belief that 'everything would be all right if it weren't for. . . . ' to go unchallenged.

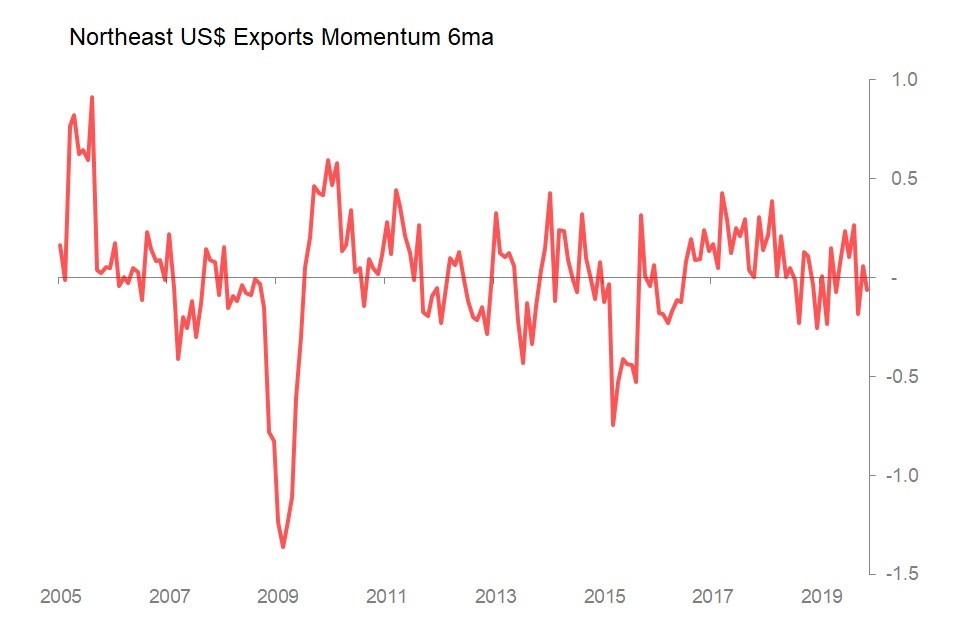

And it absolutely should be challenged, because the startling fact is that as far as either Northeast Asian exports (China, Japan, S Korea, Taiwan) or G3 imports (US, Eurozone, Japan) are concerned, 2019 was not a year when trade patterns deteriorated markedly and dramatically, or even at all, from underlying trends. Consider NE Asia's exports: the following chart track the 6m movement against 5yr seasonalized trends, expressed in standard deviations.

What the chart immediately makes unambiguous is that NE Asia's export momentum was NOT massively disrupted by US-China disputes. In fact, in the 12m to November 2019, the average monthly deflection from 5yr seasonalized trends was. . . . 0.0SDs. During that time, NE Asia's exports fell 3.1% yoy, not because they deflected from trend, but because they conformed tightly to trend. The problem, then, cannot be US-China disputes. Rather, it is the underlying trend itself.

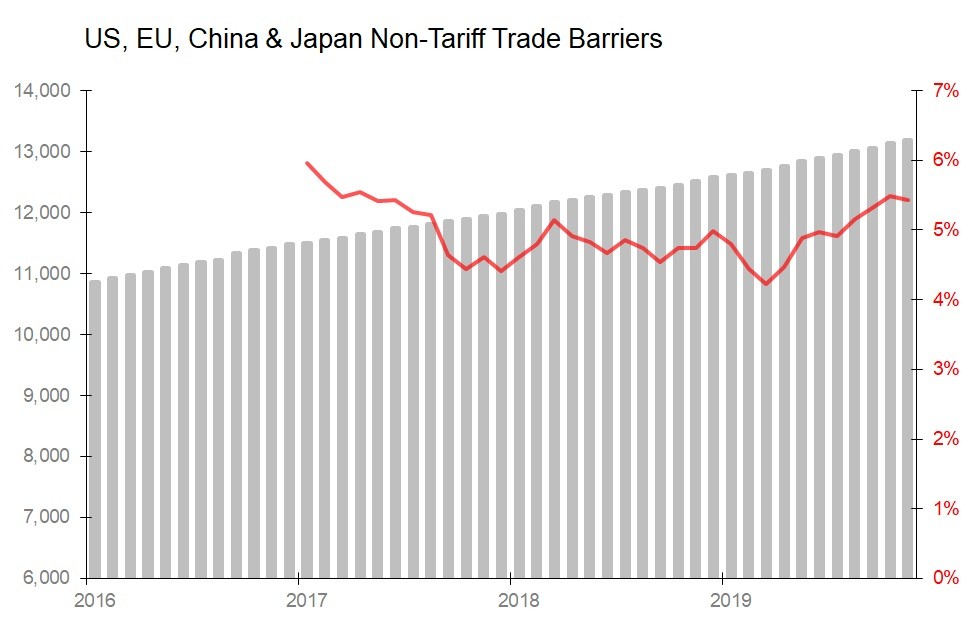

The question which must then surely be asked is 'what is killing the trend?' The most obvious answer to this is that trade lawyers in the world's largest markets are waging a quiet but unremitting war against world trade by writing a proliferating jungle of non-tariff barriers (NTBs). In November 2018, the US, EU, Japan and China had, between them, 12,514 non-tariff barriers tracked by the World Trade Organization: by November 2019 that total had risen 5.4% to 13,194. In the 12m to Oct 2018, there were 1.58 NTBs per US$ billion of imports made by these economies; by October 2019 that had risen to 1.71 NTBs per billion.

The rise has been absolutely relentless - one suspects that the forces organizing the death of world trade are now acting largely on auto-pilot, and well out of the way of direct political scrutiny.

There is a second factor which is also rarely allowed to break into the public discourse: the possibly negative impact of China's scarier political environment is having on its economy. Few international investors and traders will not know about 'the anaconda in the chandelier' aspect of doing business in China. The ballroom glitters and the prospects of a rich evening look good but . . . don't look up there because . . . there's an anaconda in the chandelier. Since Deng Xiaoping's Southern Tour of 1992, the anaconda has pretty much kept itself to itself, hasn't dropped from the chandelier onto the neck of very many partygoers that you'd notice. But it hasn't gone away, and these days, it's looking a little more interested, maybe a little tougher and hungrier, less the sort of thing you can be sure will stay up there. . .

Maybe some people are skipping the party for the time being.

And finally, attributing the world's economic ills primarily to US and China tensions allows us all not to think too much about whether some of the frailties might be attributable directly to post-Crisis monetary policies. True, it seems theoretically and empirically highly likely that near-zero interest rate policies and massive central bank balance sheet expansion has contributed to widening wealth inequalities. True, it also seems theoretically and empirically highly likely that these same policies will result and have resulted in an increasing population of corporate zombies which destroy margins and prevent productive re-deployment of capital and labour and so cripple productivity gains.

These observations are hardly even controversial, but, hell, when there's funk there's always room for. . .

Displacement Activity. In other words, the response to 2019's Grand Funk has been for central banks in the US and EU to double down their post-Crisis policies, cutting interest rates and bloating up the balance sheet once again. My Funk Index plunged to its deepest abyss in July, and by the end of that month, the US Federal Reserve had responded, by cutting Fed Funds target by 25bps to 2%-2.25%, and announcing the it would stop the very modest run-down of its balance sheet. Further 25bps cuts were made in September and October. In addition, in October the Fed committed to maintaining ample reserve balances within the banking system, including via repos - presumably in order to relieve the pressures generated by the Federal Government's own attempts to rebuild its cash position.

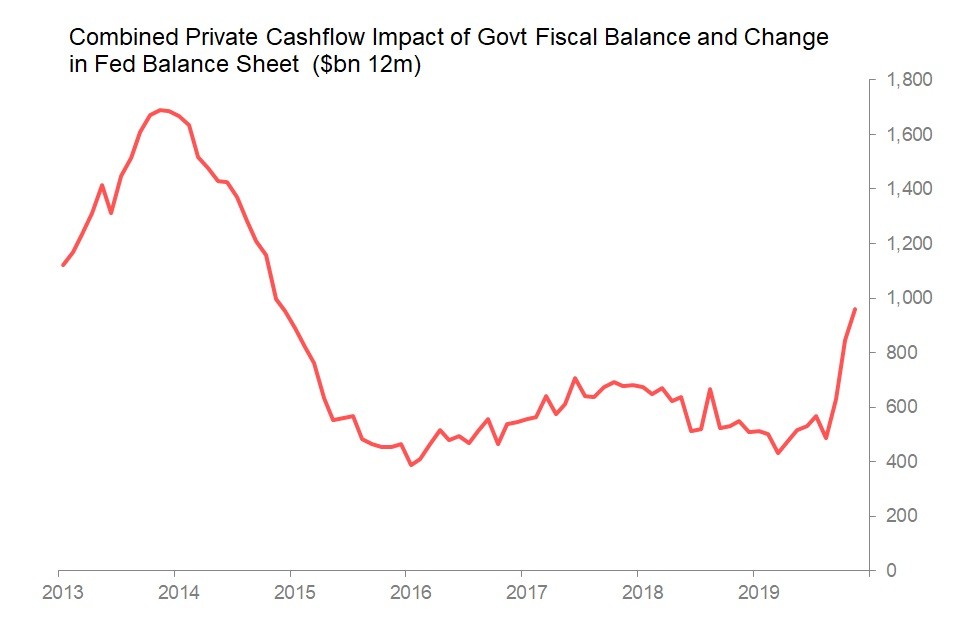

From early 2018 to August 2019, the Federal Reserve had been gradually shrinking its balance sheet, which in part offset the impact of the widening Federal fiscal deficit (ie, the Federal Government's deficit was net putting cash into the hands of the private sector, which the Federal Reserve was then quietly taking back by shrinking its balance sheet). That all changed in the latter part of 2019, with the fiscal deficit continuing to grow but at the same time the Federal Reserve got back into the business of reflating the financial system.

The combination was spectacular: the combined net impact on private cashflows of Federal Government and Federal Reserve policies went from a net positive of $486bn in the 12m to August, to $960.5bn in the 12m to November.

The Fed was not alone in doubling down: in its September policy meeting the European Central Bank decided its already-negative interest rates could be usefully made even more deeply negative, cutting their deposit rate by 10bps to minus -0.50%, and announcing it would restart its asset purchase programme at Eu20bn a month from November. As with the Fed, the results are already visible in its balance sheet, with ECB's net lending into the Eurozone banking system rising from EU113bn at the beginning of September, to a peak of Eu435bn by late November (and Eu371 by mid-December).

This combined re-commitment to monetary stimulus on both sides of the Atlantic has been spectacularly successful in seeing off the Grand Funk of mid-2019. Right now my Funk Index is at its highest level since 2017, with the strength of developed world equity markets both cause and expression of it.

Maybe 2020 will be different. Maybe central bankers won't feel so urgently the need to prop up equity markets. Maybe politicians and policymakers will find a way to stop the lawfare against world trade. Maybe some countries at least will try to discover ways to transcend the shortcomings of the post-2008/9 policy set. Let's hope so. Happy New Year it would be.