Sep 23•24 min read

HENRY HUDSON: Exploration, Discovery & Mutiny

June 24, 1611

Captain Hudson must have been in utter disbelief as the Sun rose over the wilderness surrounding James Bay: manning a small open boat with only a handful of men, they row vigorously to the north in an attempt to catch their ship, the Discovery, now sailing toward the vast waters of Hudson Bay.

Eventually, disbelief would fade and be replaced by sheer horror, as they watch Discovery deploy full sails and begin pulling away, until she disappears over the horizon.

Hudson would never be heard from again.

An Explorer is Born

At the beginning of the 1600's, international trade was quickly becoming the measure of a nations wealth and status; the English and Dutch emerging as main competitors.

For Europeans, the cultures of the Far East (Asia) continued to be the most attractive target for trade due to their wealth of silks, spices and more, but the distance between the two peoples was an obvious challenge which no one really had a good answer for: Overland routes were disconnected and treacherous after collapse of the Mongol Empire and subsequent decline of the Silk Road. The only route by sea was equally dangerous because of the sheer distance, as it required sailing around the southern tip of Africa. Both options took a great deal of time.

Thus emerged the idea of passages to the north: since the sun never sets north of the Arctic Circle during the summer months, some believed the ice might melt enough to allow ships to sail over the top of the world and into the Pacific Ocean.

In 1607, the Muscovy Company of England sought to commission a vessel to explore the Arctic in hopes of finding such a route: They acquired the 80-ton ship Hopewell and put together a crew of 10 men and a cabin boy to sail her.

Henry Hudson was hired as her Captain; his first venture into the unknown.

Hudson would become one hell of an explorer. Although not much is known about his younger years, we do know he grew up in England, and took to the seas at a young age as a cabin boy. Over the years, he would harden his skills as a seaman, working his way up until he became a Captain. His years of experience and reputation as a bold, fearless commander made him a solid choice for the Muscovy Company.

The 'Hopewell' Voyages

On May 1st, 1607, the Hopewell set off due north, reaching Greenland's eastern coast in mid-June. He followed the coast north until pack ice near the 80th parallel prevented them from going any further, forcing the Hopewell to turn back to the south. Hudson opted to return to England before the the ice returned, arriving back on the Thames River on September 15th. The voyage was not a complete loss, however, as Hudson thoroughly explored and documented much of the Arctic that was unknown, traveling further north than any had been willing or able to go. He had thus solidified his reputation as an explorer.

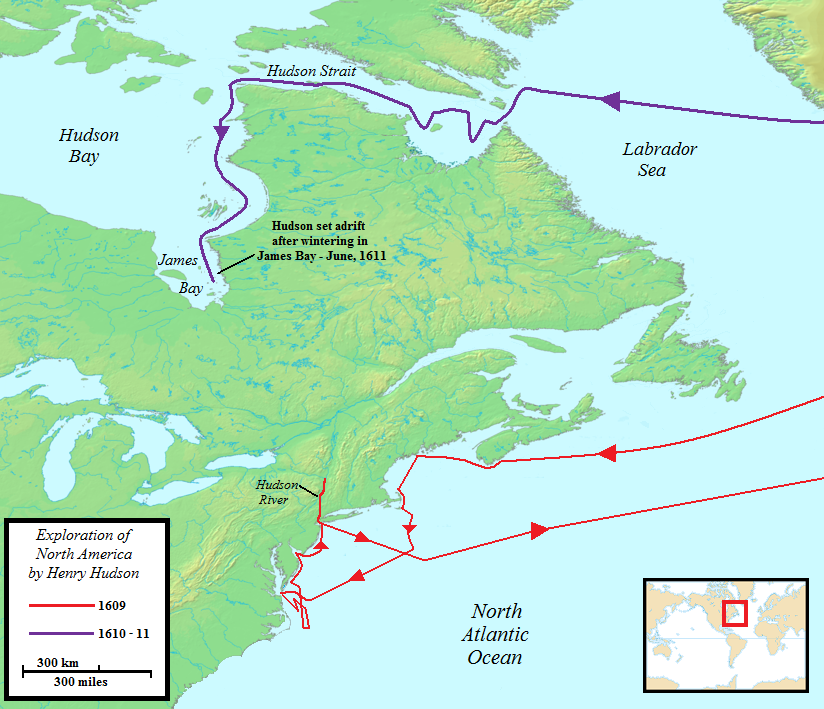

The following year, the Muscovy Company partnered with the East India Company to hire Hudson once again to captain the Hopewell in another attempt, this time to the northeast in hopes of finding a potential route to the Pacific coast of Asia by heading to the east of Greenland, over the top of Norway, across the northern coast of Russia to the Siberian Sea, then down through the Bering Strait into the Pacific Ocean.

Pictured: Henry Hudson's 1st and 2nd voyages aboard the "Hopewell."

Hudson would sail nearly 2500 miles this time, reaching as far as the other side of the Barents Sea and up into the Arctic Ocean above Russia. However, the ice would again become too much of an obstacle, even in July, forcing the expedition back west to England.

The Half Moon

In 1609, the Dutch hired Hudson to command the Halve Maen ("Half Moon") in another effort to find a northeastern route to the Pacific.

However, when they encountered ice off the coast of Norway early in the journey, Hudson - now very experienced in the Arctic seas above Norway and Russia - believed the ice would once again prevent them from going any further than he had already been.

Pictured: replica of the "Halve Maen"

So, rather than abandon the mission completely, he instead decides to turn west into the Atlantic - against his orders - in search of a route that was rumored to lead through the America's and into the Pacific: the fabled "Northwest Passage."

The Northwest Passage

Although Sebastian Cabot had somewhat explored the waters to the west of Greenland roughly a century before (in 1508), the idea of a true "Northwest Passage" appears to originate from Spanish explorers a couple decades later: Francisco de Ulloa, based on his expedition to the Baja Peninsula in 1539, believed the Gulf of California was actually the southern entrance to a waterway leading northeast where it eventually connected to the Atlantic Ocean via the Gulf of Saint Lawrence (the waters between modern Quebec and Newfoundland).

They named it the "Strait of Anián."

In the 1570's, explorer Martin Frobisher attempted to find this connection between what Cabot had explored in the northeast, and de Ulloa had covered in the southwest, to confirm such a connected strait existed, but was turned back by the ice flows of the great north, hence his naming it the "Mistaken Strait."

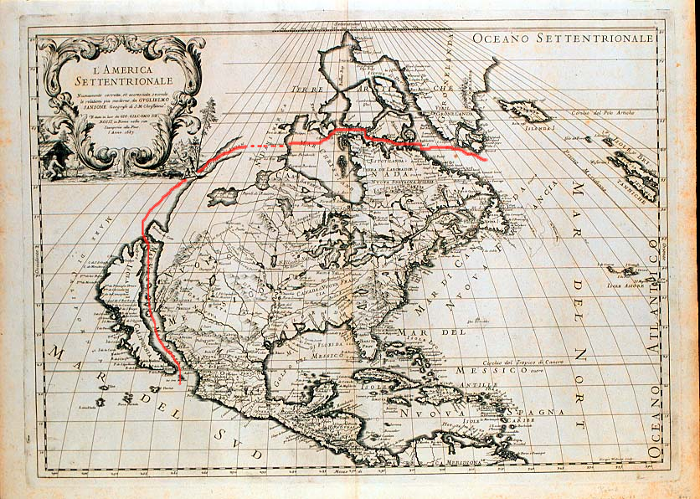

Note: This may sound like a ridiculous premise in the context of today, but it's important to point out that, in the 16th and 17th centuries, not much was known about the interior of the American continent. The map below is from 1687, showing the rumored "Strait of Anián," which some explorers believed connected the Atlantic and Pacific, then continued south to form the "Island of California."

The New World becomes the New Netherlands

Hudson & the men of the Halve Maen reached Nova Scotia in July, 1609. From there, they navigated to the south, exploring the eastern coastline of the American continent throughout the summer, searching for an entrance to the Strait of Anián further south from Frobisher's "Mistaken Strait."

In September, he located what we know today as "The Narrows;" the strait separating Brooklyn and Staten Island, which serves as the entrance to New York Bay. Considering this a possible entry point to the passage, Hudson sailed north along the west side of Manhattan Island on the river that now bears his name.

They spent 10 days exploring north until it became obvious the waterway was in fact a river rather than a strait (making it as far as where the city of Albany sits today). With the winter months on the way, Hudson decides to sail home rather than risk pushing onward and having to make winter camp in the unknown. The Halve Maen proceeded back out to the Atlantic and pointed east, arriving home in England in November, 1609.

The Virginia Company

This 1609 expedition would become one of the most thorough of the New World up to that point, with the Dutch leveraging Hudson's mapping of the region and relations with native tribes to establish settlements by 1614. The trading posts set up along the Hudson River would become the foundation of the New Netherlands, including the city of New Amsterdam (today, New York City), giving the Dutch a huge advantage in international trade, specifically over the English.

Hudson, although having not yet found a new route to the Far East, had still explored a great deal of never-seen-before territory, and established new trade relations in the New World. Thus, he becomes the a celebrity in Europe, as well as a highly-sought-after captain for all European trade companies.

As such, in 1610, he is hired yet again to continue his exploration of the Americas, this time by the Virginia Company (the British didn't want Hudson exploring on behalf of the Dutch again), to build additional trade relationships and, hopefully, find the Northwest Passage. The first crewmate Hudson signs on is his teenage son, John, as cabin boy; his first expedition.

The Virginia Company had sponsored many explorations of the New World in the years prior, which led to the eventual founding of Jamestown and colony of Virginia in 1607, and the birth of the tobacco trade.

For this new expedition, they assemble a crew of 22 men for Hudson, and issue him one of their finest - and fastest - ships: the Discovery.

The Labyrinth Without End

Pictured (foreground): Replica of "Discovery" at historic Jamestown, VA.

Fun fact: "Discovery" is depicted on the back of the State of Virginia's minted quarter, alongside her sister ships "Godspeed" and "Susan Constant." The three ships landed at Jamestown in 1607 and established the first colonies of Virginia.

For this expedition - his fourth as a Captain - Hudson plans to explore further to the north in pursuit of the Northwest Passage, since the previous year's exploration of the mid-Atlantic coast yielded only river access.

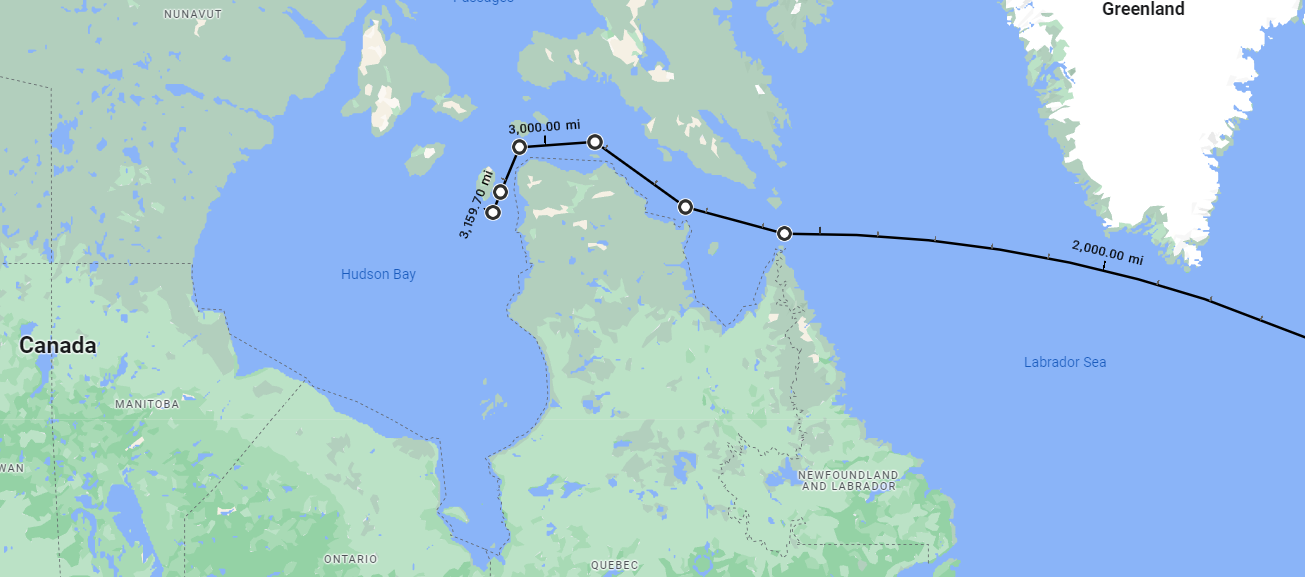

By the end of June, 1610, the mariners of Discovery make it across the Atlantic to the Canadian coast near the northernmost tip of Newfoundland and Labrador, and enter the "Mistaken Strait."

They pressed onward to the northeast along the southern coast of the strait throughout the month of July. They are forced to make a slow go of it due to the amount of ice flows crowding the open water; the same ice which forced explorers Cabot and Frobisher to turn back decades before.

But Discovery was chosen for this reason specifically: her light weight, speed and maneuverability made her the perfect choice for dodging islands of ice as they flowed south from the Artic. Although they endure many close calls, adding to increased tensions of the men aboard, Discovery and her crew are able to continue onward through the strait to the Northwest, one stress-filled day at a time.

Discovery covers another 500 miles until finally, on August 3rd, Hudson and his men round the northern tip of Quebec near Digges and Mansel Islands, and look out upon nothing but an vast open sea as far as the eye could see.

In this moment, one can imagine the blend of excitement and emotion Hudson must have felt: after years of searching, he believes he may have finally found the seaway which would bring him, and the many after him who would inevitably follow, to the Far East and its many riches.

In reality, Hudson had entered what today is known as Hudson Bay (since, even though he was not aware of it at the time, he was the guy who discovered it); a massive body of saltwater covering nearly 500,000 square miles; so large the shores on the opposite side are far beyond the horizon. He is the first European to lay eyes on the bay, pushing past Sebastian Cabot's expedition of 1509, who was unable to make it through the ice of the "Mistaken Strait;" renamed to what we know it as today: the Hudson Strait.

Hudson obviously had no way of knowing any of this as he sailed into the bay's open waters. To him and his men, they had conquered the Norwest Passage.

Pictured: The point at which the men of Discovery discover Hudson Bay, August 1610.

But now, with summer coming to an end in mere weeks, and a several-months journey back to the comforts of home, Hudson and his crew sit at a decision point: if they wish to make it back before the end of 1610, now is the time to end the expedition and make way for England, before the cold winds, snow and ice return and trap them in the Arctic. Hudson gathers his crew to present their options:

Document the discovery of this "new sea" for future expeditions and turn back for England, or;

Continue onward into the sea and locate a suitable place to set a winter encampment, then resume the expedition westward - to the Pacific and shores of Asia beyond - the following spring.

After a close vote, the men decide to remain in the bay and continue on to the west (and, hopefully, to the Asian coast) once the pack ice melts in the spring/summer of 1611.

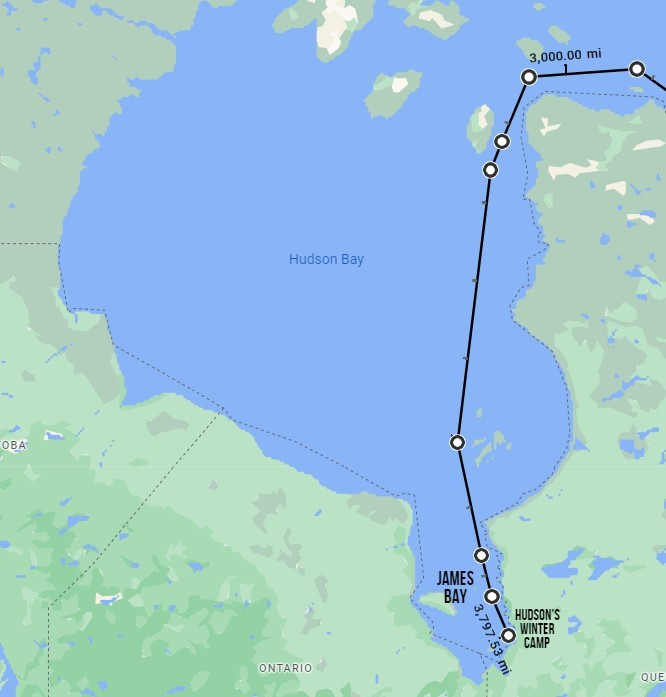

Right now, their priority is pointing Discovery due south and following the coast as far as this sea and the seasons will allow. They spend the ensuing weeks exploring the islands and shores of the eastern part of the bay on their way south, until the open waters ahead of them become surrounded by land within what appears to be a smaller bay. They explore the reaches of this bay until snow begins to fall in October.

The decision to head due south into the bay was driven by the need to get as far away from the Artic Circle as possible in search of more temperate (tolerable, survivable, etc) winter weather.

And, to their delight, they would not only find Hudson Bay allowed them to reach the same parallel as their London homes, but also a small bay with a good amount of depth, which allows them to move their vessel close to the shore; a perfect place to anchor Discovery where the pack ice is less likely to buckle her hull.

On November 1st, the men drop anchor and go ashore to locate a spot worthy of winter camp. By the 10th, Discovery is entrapped in the ice.

Here, on what today is the southeastern coast of James Bay, the men now have their new home.

Thus ends Hudson's expedition of 1610.

After "3 months in a labyrinth without end," as navigator Abacuk Pricket would write in his journal of their journey through the ice, rocks and islands of Hudson Strait and Bay, the men begin moving supplies to shore to set up winter camp.

They have mere weeks to construct shelter and hunt for all the food they will need to survive until the following spring.

A Wilderness of Ice and Snow

While they sit in the relative safety of an enclosed bay, and on the same parallel as their England homes, they are unaware of the weather patterns which allow Europe to remain relatively temperate in winter, and keep the Canadian north a frozen, windswept tundra: Today, we know the Atlantic current continually brings warm air from the west indies up to Europe, pushing back the Artic winds to the north.

In the great north of the Americas, however, no such ocean current exists to protect the land from the cold. Instead, the winds blow cold air due south from the Arctic onto the continent all winter long, directly into Hudson Bay.

As such, the winter they are about to live through will be worse than any European to that point in history has ever endured.

Note: While we don't know the full details of what the men of "Discovery" went through that fateful winter (journal entries after October were rare, for good reason), we have a good idea what they must have gone through based on later expeditions to the region:

Two decades later (1631-1632), Thomas James (whom James Bay would later be named for) explored the Hudson Bay extensively and, having left England planning to winter on the bay, came far more prepared than Hudson's crew of 1610.

James' men came with a bounty of food, supplies and tools. They constructed three structures on the land to endure the cold and protect their food stores. They also brought with them far more in terms of furs and coats to keep them warm. However, three of James' men would still perish that winter from illness and frostbite.

They described a cold so bad that unexposed flesh would freeze almost instantly if one were outside. If they needed to go to their ship trapped in the ice just off shore, the men found the short trek unbearable and would have to turn back, or give up and succumb to the cold.

James himself described the experience of that winter as "so extreme that it was not endurable."

By October 1610, while Discovery was still sailing south, snow had already begun to coat the region around James Bay.

By November, the bay began to freeze. Soon they would be surrounded by what one of the men described in his journal as a "wilderness of snow and ice."

Hudson's men constructed a small structure to house them and their fires, providing at least some protection from the elements; enough to keep them alive, perhaps, but not enough to provide any semblance of comfort or calm.

Tensions would rise between the men early on, as outlined by a vague entry in navigator Pricket's journal from mid-November: the ships gunner - John Williams - died, and likely by Hudson's own hand: "God pardon the Master's [captain's] uncharitable dealing with this man" was all Pricket committed to paper, implying Hudson and Williams had a disagreement they were unable to resolve. Tempers had likely risen as they began to experience the harsh cold of the bay, pushing Williams to make a choice that might have threatened the crew and/or expedition (perhaps even an early attempt at mutiny), which unfortunately would have forced Hudson to make an example of him.

The rest of the winter was uneventful in the eyes of documented history, aside from everyday routine of attempting to stay warm and nourished enough to survive the unrelenting cold and wind.

Yet, this time was likely very eventful for those who experienced it, huddled by the fire in their makeshift shelter, as evidenced by the fact they wrote down very little; ink would likely have frozen, paper would have become brittle to the touch, and even their fingers would have been unusable for a task as delicate as committing quill to paper. A truly miserable existence, as one can imagine.

They would endure this existence for several months before the days began to lengthen, and flocks of birds began to migrate back into the bay; a sign that warmth would soon return and begin breaking the pack ice which currently maintained its tight hold on their beloved Discovery.

Once the ice had melted enough to float their shallop - a small, open-top boat used by the crew for fishing and exploring shallower waters or shorelines the Discovery could not navigate within - Hudson had it stocked with supplies for a few days, then set off to explore the eastern shores of James Bay in hopes of connecting with the locals for trade (as he had done on his previous expedition up the Hudson River in 1609).

While he could see smoke from their fires in the distance, he was unable to make contact with anyone and returned to Discovery, where he had left his men to prepare her for when the ice broke and set her free.

Unfortunately, while away on his 9-day excursion, the tensions which had built throughout the winter had come to a head; several of them were too ill to participate in the work necessary to cast off once again, and those healthy enough to contribute struggled to do so. Food supplies had become dangerously low. Further, they knew once Discovery was loose from the ice, Hudson would likely order them to continue onward to the west in search of the Northwest Passage rather than return home.

Hudson continued to be a man on a mission; one he had spent years pursuing to no avail, and he showed no signs of relenting.

Thus, some of the crew used Hudson's short time away to plot mutiny.

The Ice Thins & the Plot Thickens

On June 17th, 1611, the pack ice in James Bay finally melts enough to set Discovery free. The crew raise anchor and point north for the "open sea" of Hudson Bay.

After months of enduring the harshest winter the men have ever witnessed, 22 of the men and Hudson's son - John - have survived, as has the Discovery. Yet, several have become too weak or ill to contribute to the work a ship requires, and spend most of their days bedridden in the cabins below deck.

Afloat once again on the open waters must have felt like a victory for the beleaguered men, but they still remain far from the finish line, as well as without a clear idea of what the plan is going forward: Will Hudson order them further to the west in search of the Passage? Or will he opt to turn back for England? One can imagine, since Hudson issued no orders one way or another upon hoisting anchor in James Bay, that he too was uncertain about whether or not to continue on to the west in their current state. However, it does not take long for his determination to inevitably return.

In the coming days, Hudson's makes his choice clear: He is resolved not to fail again, and will find the passage to the Far East; they will continue onward to the west and sail into the Pacific Ocean.

He orders remaining food to be issued equally amongst the men (roughly 2 weeks worth each), and announces his plan for them to continue to the west, exploring the rest of the bay until they locate the route to the warmth of the South Pacific and the Asian coast. To account for supplies, they will continue to fish, hunt and seek out trade with native populations along the way to secure what they need to survive.

This decision does not go over well with the crew.

On the night of June 23rd, while they sit at anchor at the entrance to James Bay making preparations to continue westward, rather than northward and towards home, members of the crew gather below and approach their navigator, Abacuk Pricket, while Hudson sleeps.

From this point onward, we must take the story with a grain of salt, as the only side we have today is that of the mutineers who did eventually return to England; the majority of it being documented by Mr. Pricket.

Henry Greene (supposed leader of the plot) and Robert Juet (current 1st mate) share their plan to take control of Discovery and change course for home. After claiming they have the support of most men aboard, they ask Pricket if he is willing to join them. At first, he claims he is reluctant to support their effort, urging them to remember the fate that awaits them in England as mutineers - likely the gallows - should they make it home. Greene, however, expresses resolve on the matter, telling Pricket, "I would rather be hung at home than starved abroad."

Pricket again refuses to support the effort, but does agree not to interfere with their plans should they go through with it, under the condition they do not harm anyone in the process. This likely saves Pricket (along with his skill as a navigator) from ending up on the losing side of the mutiny.

Thus, Green, Juet and their supporters put into motion their plan to take control of Discovery at dawn.

Mutiny

Just as the first ounces of light begin to come up over the eastern horizon, Hudson exits his cabin only to be immediately seized by members of his own crew, his hands bound by ropes. Hudson shouts angrily at them, but to no avail. Those below deck, who are shocked to hear their commander's cries for help, find themselves too weak to rise from their bunks, let alone fight back against the mutineers in any capacity.

Greene declares he is taking command of Discovery, and orders the shallop raised from the water. They fill it with a few weeks of supplies, some tools, a gun, powder and some shot, and a small pot for cooking; this is all they leave for Hudson and those who will go with him to survive.

The mutineers then force a bound Hudson, his son, and the ill/weak from below into the small boat and begin lowering them into the bay. Once on the water, Greene orders the rope cut; Discovery immediately begins to pull away toward the north, leaving the shallop adrift in the waters of James Bay.

After freeing Hudson from his bindings, the 9 crewmates in the shallop attempt using a makeshift sail and their oars to keep pace with Discovery, and do so successfully for many hours, until Greene - seeing the shallop in pursuit - orders deployment of the topsail and mainsail. They catch the wind and pull away in haste, eventually losing sight of the small, beleaguered vessel.

It is the last time Hudson will be seen.

Discovery returns Home

The remaining 14 crewmen, although now liberated from their expedition, are not yet home free, as their journey home would continue to be plagued by misfortune.

5 would be killed - including their new captain Henry Greene - in an ambush by a local Inuit tribe on the shores of the Hudson Strait while they hunted for food.

Robert Juet, who took command following the death of Greene, would perish from starvation mere days away from the coast of Ireland.

Note: according to the survivors of the expedition, the two supposed leaders of the mutiny happened to die on the way home. Just something to consider.

They would finally arrive in Bear Haven, Ireland, on September 6th. After a rest and resupply, they completed the final leg home to London. Of the original 24 who had left 16 months earlier (Hudson, his son, and the 22 men recruited by the Virginia Company), only 8 return.

In the ensuing years, those 8 men would predictably become the subject of scrutiny for the events of early summer 1611. But in the end, even with tarnished reputations, they would all be acquitted of their charges due to the amount of knowledge they brought home from their expedition. These men had travelled further than any other was known to have gone, and came the closest to finding the fabled passage, all while enduring forces of nature no European had yet seen and lived to tell the tale.

Thus, the crown sees more value in keeping these men alive for the benefit of future exploration.

Many future expeditions would return to Hudson & James Bays to continue what Hudson and Discovery had explored, as well as search for the stranded Hudson and his meager crew; the earliest by fellow explorer Thomas Button a year later in 1612.

While some believe he and his men could have potentially survived their desertion in the bay, or perhaps even made an overland journey to friendly tribes or trading posts to the south, all efforts turned up no credible sign of Hudson. The remains and memories of Hudson, his son John, and the 7 men who joined them, are likely a permanent addition to the great northern wilderness of Hudson Bay.

Thus concludes the story of Henry Hudson and the Mutiny of the Discovery.

In spite of his bitter, unknown end, Hudson today remains one of the most influential explorers of the past 1000 years, having pushed further into the unknown than all those who came before him. He created paths many fellow explorers would inevitably follow and build upon over the coming centuries.

After many failed attempts in subsequent years by many explorers, the mysterious "Northwest Passage" would finally be found by legendary Norwegian explorer Roald Amundsen aboard his ship the Gjøa...in 1906.

But theirs is a story for another time. Until then, thank you for reading; it means the world to me and I hope you learned something new and fun. Skol!

-Trygg

Pictured at the top: "The Last Voyage of Henry Hudson" by artist John Collier, depicting Hudson, his son and a loyal crewmate adrift in James Bay aboard Discovery's shallop.