Nov 19•10 min read

This Is Not Your Father’s Economy

Advertisement slogans are often catchy and hard to forget. However, only a few reach iconic status – including one that failed miserably when it first came out.

After getting annihilated by the big three Japanese automakers (Honda, Nissan, and Toyota) in the 1980s, by 1988, General Motors (GM) realized that they needed to make a wholesale turnaround. It focused on its Oldsmobile vehicles, which were considered to be made for retirees only. So in 1988, the company gave the cars a facelift to try to attract younger customers.

But GM also understood that a complete rebranding was required to inject new life into the new vehicle.

So it came up with a new advertisement campaign slogan: “This is not your father’s Oldsmobile.”

The advertisements were hip and full of energy. Oldsmobile even hired music icon Tina Turner to sing the theme song in an attempt to shake off the old, stuffy imagery that associated Oldsmobile with retirement homes and country clubs.

But it was all to no avail. Oldsmobile’s sales figures still slumped and fell farther behind its Japanese competitors. The redesigned cars still drove like boats, with the build quality nowhere near their Japanese counterparts. Plus, the ad campaign alienated its elderly customer base while failing to draw in a younger crowd.

But the slogan lived on, and it morphed into a universal, descriptive tagline with a life of its own.

Whenever one wants to describe a product, a situation, or anything that’s drastically different from its predecessor, then you often hear, “This is not your father’s _____________” (just fill in the blank).

Given that 2023 is almost over, now is a good time to take a step back and examine how the economy’s changed compared to decades past, and what’s lurking beneath the surface for 2024.

After all, “This is not your father’s economy.”

But it remains to be seen whether it’ll be more successful than Oldsmobile’s rebranding.

Strap in. And let’s go for a quick ride.

Thanks for reading Espresso! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support our work.

Can the Government Keep Paying Its Bills?

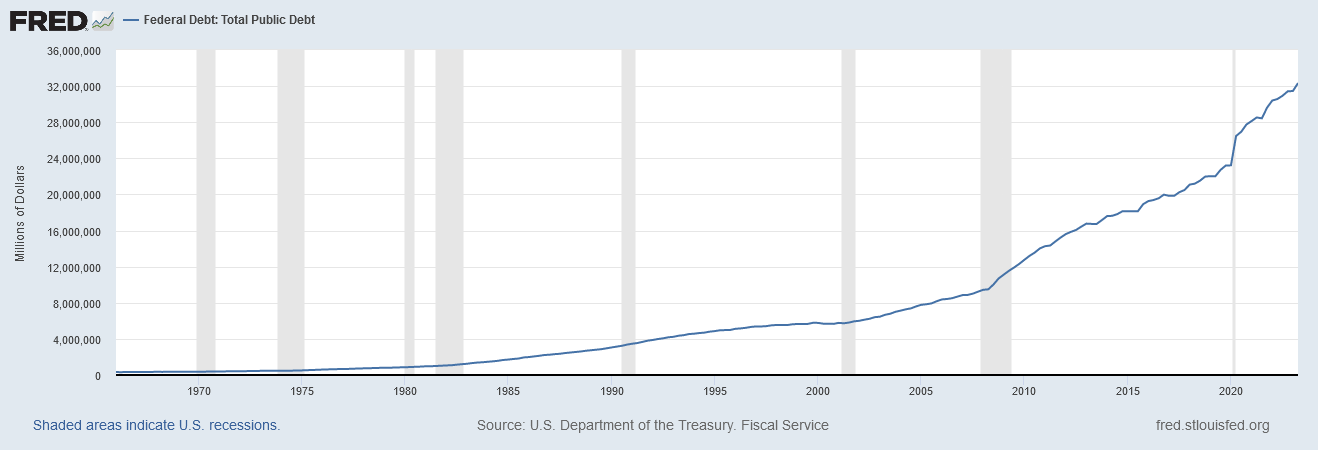

In 2020, the liability side of the U.S. government’s balance sheet really ticked up, courtesy of all the COVID-19 programs and financial stimulus packages.

But even though COVID-19 is mostly behind us, that trend has continued today. First, there was the financial support for Ukraine after Russia’s invasion. And now, tag on the military expenses for the war in Gaza. The amount of U.S. government debt won’t be coming down anytime soon.

Source: St. Louis Fed

The debt today sits at $32.22 trillion.

With the ongoing wars and the funding liabilities of all the big government programs, the government does not seem to show any inclination to curb spending. Expect the debt to keep ballooning for decades.

So the question now becomes: How to fund these liabilities?

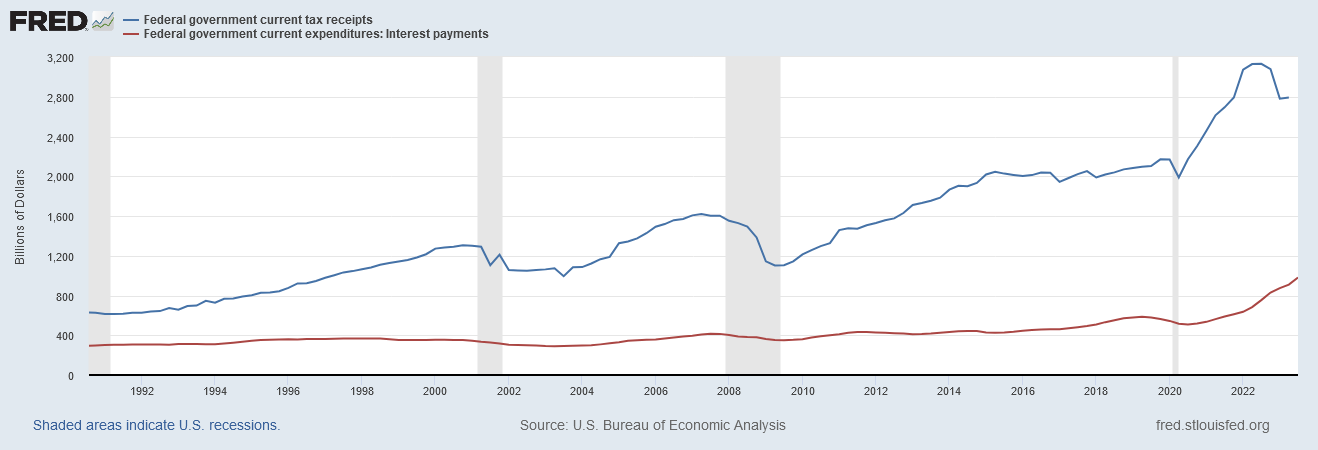

The blue line in the chart below is the revenue that the government collects from taxes. The red line is the interest payments it has to make to fund the liabilities.

Source: St. Louis Fed

Currently, tax income covers the government’s interest payments with about $1.8 trillion left over. But notice that the red line is trending higher while the blue line is trending lower.

The Federal Reserve may have paused rate hikes, but regardless, with higher funding rates, the constant expansion of government debt means interest payments will continue to rise.

The USD Game of Thrones

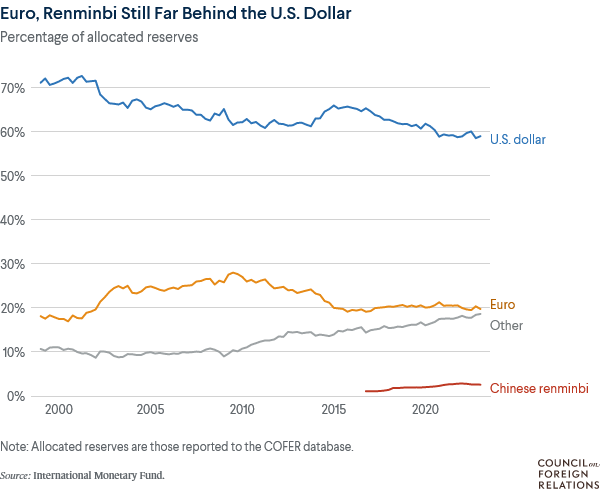

Just like in our fathers’ days, the U.S. dollar (USD) is still the de facto global reserve currency.

Everything is priced in USD. Countries will accept USD for trades as well as buy U.S. Treasuries.

But for the first time since World War II, we are witnessing formidable attempts from other countries to pivot away from the dollar.

We discussed the implications of this back in November of last year.

The chart below shows how other currencies, like the Chinese renminbi (RMB), are gaining adoption as countries reduce the amount of USD in their foreign exchange reserves.

Source: Council on Foreign Relations

But this shift away from the dollar won’t be easy. As we mentioned last November, the dollar is still the king. Supplanting it will be a monumental effort that requires tremendous amounts of resources and cooperation from other countries to pull it off – assuming it can be done.

As a perfect example, look at a recent conflict among the BRICS nations (Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa), which are leading their own attempts to dethrone the dollar. The countries had a deal that Russia will sell oil in Chinese RMB. But that did not last long. Just last month, India protested and rejected Russia’s request to pay for its oil exports in RMB.

The BRICS countries cannot even agree on a common currency to transact with.

Moving forward, the scenario that’s most likely is that the rest of the world may reduce their holdings in USD by not buying as many U.S. Treasuries. But, as long as commodities are still priced in USD (which I think they will be given that USD is the cleanest dirty shirt in the hamper), other countries’ foreign exchange reserve portfolios will still tilt toward the dollar.

High Inflation Will Persist

This week, the Fed got more confirmation that inflation is slowing, as the CPI and PPI numbers for October came in under expectations.

But make no mistake: We are likely just in the lull before the next wave of inflation.

A growing global population means increasing demand for energy – and not just any energy, but energy that is cheap, efficient, stable, and reliable. This might be a formidable task for governments around the world.

With the concentrated attention on green energy, which has yet to prove that it can meet those criteria above, it certainly remains a distraction as well as a disruption to the development and enhancement of the traditional energy industry.

Current energy policies are out of whack. They could be devoting effort and resources to a parallel scheme where green energy continues to improve its technology while traditional energy providers also get resources to be more efficient and less polluting.

Instead, governments around the world are forcing people to switch to green energy and forego traditional energy regardless of the financial cost – even as green technology is immature and the supply is inconsistent.

We have mentioned in several articles about how the lack of investment in infrastructure and the direction of government policies has shaped the current landscape of the energy market.

Energy prices will be the key driver of the inflation narrative in the future.

There’s Nowhere to Hide Anymore

Compared to before, the global economy is so intertwined and interconnected. Which means there is no more firewall from bad conditions in other countries.

A few decades ago, hedging options and protection measures could be had. But now, every economy in the world is linked up with one another, and it is like dominoes. If one piece falls, the others are more than likely to feel that impact.

Case in point: As the West is enacting quantitative tightening (QT) and hiking rates, China and Japan are still printing money and keeping interest rates low in hopes of trying to stimulate and revive their economies.

While the West is trying to reduce liquidity, the East is still providing ample liquidity to the market for risk-on assets.

We are truly living in a global economy. If a G7 country or region falters, there will be a high likelihood the global economy will go down with it.

The Japanese yen (JPY) carry-trade is a good example. As we explained here, over the past few decades, investors and institutions borrowed cheap yen at almost no cost to invest in other risk-on assets or real estate. But Japan recently started signaling that it might end its yield curve control (YCC) program and let borrowing costs rise higher.

Should JPY appreciate as well, liquidity drops, bringing risky assets with it.

Here’s an example per our chart from a few months back:

This is a daily chart of the S&P 500. The yellow arrow points to the long, red candle that was recorded on July 27, 2023 – the same day the BoJ announced the YCC “tweak.”

As one can see, the S&P 500 dropped like an anchor that day. In fact, it was at the highest point of 2023 at 4607.07.

With the global economy more entangled than ever, we can expect more cooperation between central banks in the future. But that won’t be enough to resolve the financial debacle that decades of bad policies – political, fiscal, and monetary – have created.

The Brave New World Economy

High public and private debts. High interest rates. Heightened geopolitical tensions throughout the world. Highly interconnected global economy without hedging options. Increasing commodity, food, and energy prices. About the only things that are low now are people’s morale and trust in government.

This is not your father’s economy. That is for sure.

Yes, we’ve been here before, when the U.S. saw high inflation and geopolitical turmoil a few decades ago. But when former Fed Chair Paul Volcker slayed the inflation beast in the 1980s, he did not have the high U.S. government debt load to contend with.

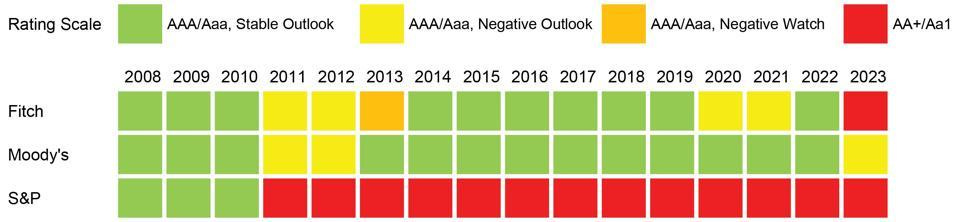

On November 10, Moody’s indicated that it intends to downgrade the U.S. sovereign rating from “stable” to “negative,” which caused quite a stir and elicited consternation from Washington, D.C.

The ratings agency determined that the U.S. government now has a higher default risk due to uncontrolled spending and rising interest rates that further exacerbates U.S. debts. Moody’s is the only agency that still has the US credit rating at AAA/Aaa, while the other two, Standard & Poor’s and Fitch, have already downgraded U.S. credit to AA+/Aa1.

Source: Moody’s, S&P, Fitch Ratings. Chart by Hanlon Research. – Via Forbes

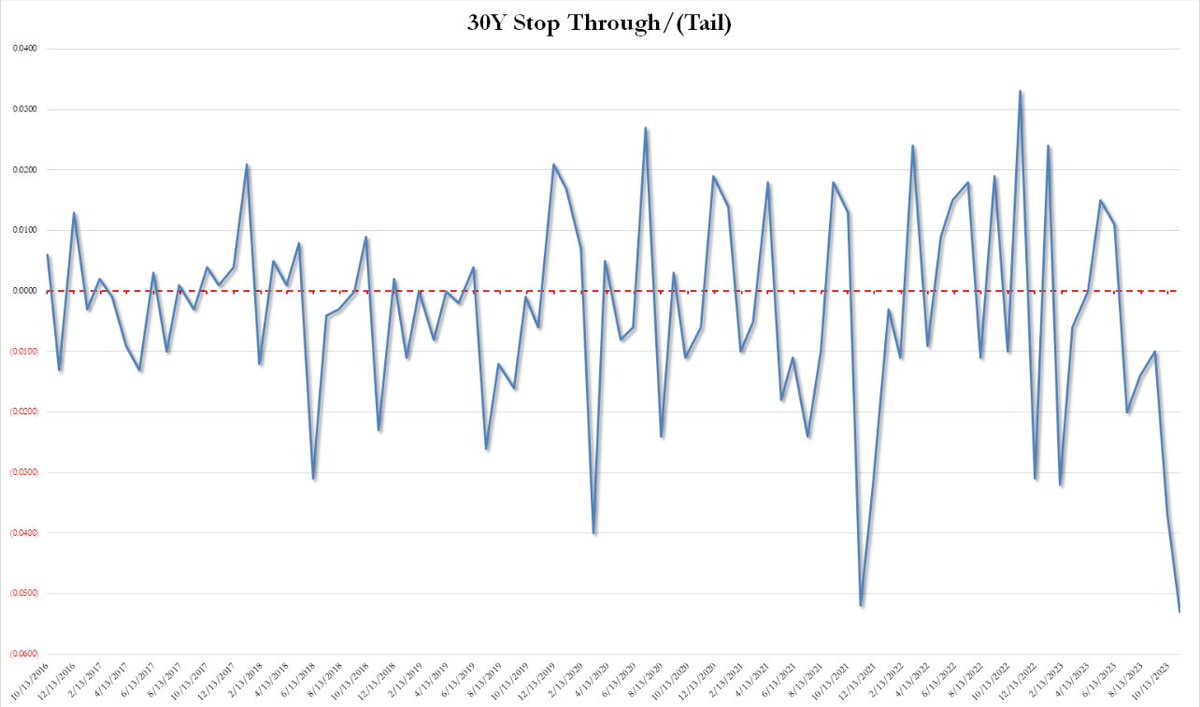

Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen was the first to jump out and publicly state that she disagrees with the downgrade. But that same day, Treasury bonds had a disastrous auction, when yields for the 30-year bonds had to jump up 5.3 basis points from pre-auction trading to entice investors to buy them. The larger that “tail” (the difference between the two yields), the weaker the auction. And this was the largest tail since 2016.

Source: ZeroHedge

The mismatch resulted in no buyers showing up at the auction. The primary dealers (investment banks such as Goldman Sachs and JPMorgan) were forced to absorb all the bonds that did not sell, which is around 24.7%, well above the normal average of 11% in a lackluster Treasury auction.

Back on June 1, when Congress passed the bill to raise the debt ceiling into 2025, the Treasury General Account, the checking account of the U.S. government, was almost empty. When the bill passed, the Treasury had to start issuing Treasuries to refill the TGA for the government to pay its bills and function properly.

Could it be that the market is now oversupplied with Treasuries?

Possibly.

But by the same token, foreign bidders’ participation rate for this disastrous auction went down to 60% from 65%.

So perhaps, the market is quietly agreeing with the rating agencies.

Faith in Treasuries is slowly chipping away as the U.S. government continues to spend like a drunken sailor.

If things continue on this trajectory, one has to ask, who is going to buy Treasuries and make the primary dealers whole?

In the past, that was the Fed’s job. But this time around, not only will the Fed lose credibility, but buying Treasuries means more quantitative easing (QE) and higher inflation.

If that happens, central banks will have to go back to hiking rates again, which means risks for the credit market. And the entire cycle starts again.

Sounds like a perfect storm to kick off the second wave of inflation.

It is quite a conundrum.

And there is no easy way out of this one.

Yours truly,

TD