Aug 01•11 min read

How Blockchain Dethrones the Dollar

The Blend: Digital Money Threatens the Dollar’s Reserve Status

My long-term view was firm. The U.S. dollar would not lose the title of global reserve currency.

This was even after JPow manned the infinity printer, Ray Dalio rolled out his educational series called “Principles for Dealing With the Changing World Order” on YouTube, and Russia and China invested in one another’s currencies in the hopes to form a competing trade bloc among BRIC nations (Brazil, Russia, India, China).

But I was forced to change my assumption a few weeks ago.

What changed my mind was applying Zoltan Poszar’s theory on a changing monetary order with what’s happened in crypto. Specifically, what happens when new swap technology enters the market.

And to roll out this view, I’d like to dive into some major shifts happening at the global level. I hope this helps bring some clarity on why I’ve been so hungry to write about this topic. To satiate my own appetite, I used The Blend today to cover three topics all related to this overarching thought.

Consider this piece as me using opinions and facts that are not my own to simply connect dots on this theory.

In the first section, I’ll go over the new worldview called Bretton Woods III. Then, I’ll dive into technological progress with global banking infrastructure. And finally, I’ll hit on a worry that has barely started to surface with academics regarding what might happen to the dollar.

The Dollar’s Days As the Reserve Currency May Be Numbered

You’ve heard me mention it and likely have heard it from several other keyboard warriors like myself: Bretton Woods 3 (BW3).

It’s a loaded topic that fuels heated opinions among economists, traders, and even retail. It hits on quite literally the most important subject in finance: the global monetary order.

The legacy of Bretton Woods began in 1944. This defined an era where global currencies were pegged to the U.S. dollar, which in turn was backed by gold. The system enabled stability and predictability, with the dollar ascending to a dominant role as the world's reserve currency.

This v1 of BW ended in 1971 when Richard Nixon severed the dollar’s link to gold, bringing v2 into the arena.

It brought along with it fiat currency. Fiat means, “Let it be done.” Or in other words, the “$10” written on the dollar bill makes it worth $10. Meaning gold was no longer behind it, just the formal decree from the supervisor of the money printer.

This thrust central banks even more into the limelight, as their task of maintaining price stability became more difficult.

And since the U.S. was becoming the reserve currency, it meant it needed to run a heavy trade deficit. This allowed U.S. dollars to make their way out into various markets. The trade relationship between the U.S. and China highlights this dynamic the most, with China holding well over a trillion dollars’ worth of U.S. Treasurys until recently.

It also brought about the petrodollar concept. The U.S. helped oil producers by paying in dollars. This in turn allowed future oil buyers, banks, etc., to help finance trade from these producers. And in turn, give rise to the entire oil market of the Middle East.

The U.S. dollar was the conduit of global trade. It’s in part why 88% of foreign settlements involved the U.S. dollar. As easy as it is to hate on petrodollars, eurodollars, etc., this policy did address many global trade concerns (e.g. currency valuation changes, settlement, currency acceptance).

According to rate specialist Zoltan Pozsar, who had stints at the Federal Reserve Bank of New York and Credit Suisse, this all changed with the Russian invasion of Ukraine in 2022.

The severe sanctions levied against Russia denied it access to a significant portion of its foreign exchange reserves, including its supply of dollars. This incident set a precedent: If you go against U.S. policy, then your assets can be confiscated. It was a moment where a global hegemony abused its power to wage financial warfare.

That marked the pivot to v3 of Bretton Woods.

Countries now look at U.S. dollars in their bank accounts and see a new degree of risk attached to them.

They realized that the dollars on their balance sheets mean less than the commodities they could sell to the world. Meaning it suddenly put an emphasis on investing in commodities markets and supply chains.

This is why we now are beginning to see trade agreements where the U.S. dollar is no longer involved. It’s a shift that will take significant time to usher in, mostly because of the sluggish nature of government and old financial infrastructure.

But what looks to be most interesting here is the fact that the technological infrastructure for trade is about to get a massive upgrade, which we can hit on next before we start to draw on a few conclusions…

Global Regulators Are Experimenting With DeFi

If we take a look at the websites of the Bank for International Settlements (BIS) or the International Monetary Fund (IMF), a few of the largest banking institutions in the world, there is a common theme: tokenization and digital money.

Screenshot of the BIS homepage. Notice the articles at the top-left and bottom-right.

To put it plainly, central bank digital currencies (CBDCs) are coming fast. Which means our current technology needs to be upgraded.

Two notable solutions are the Monetary Authority of Singapore’s Project Guardian and the BIS’ Project Mariana.

Project Guardian is based on a distributed ledger technology called Multi-CBDC Bridge (mBridge). It’s a fancy name for swapping CBDCs. Or for the crypto degen among us, it’s an even fancier name for using Uniswap v2 AMM tech to swap some tokens.

If you read the report on Project Guardian, which is getting help to build the tech from banks like JPMorgan, it’s an extremely long winded explanation of how tokens can swap efficiently.

I will say that Wall Street is really good at taking some awesome tech and making it extremely boring.

Anyways, just as most of us know, you can now swap assets at the tail end of the liquidity curve… Think Vietnam swapping tokens with Costa Rica without needing the U.S. dollar here.

The other project making the rounds is Mariana. This one also has the Monetary Authority of Singapore as well as the BIS, the Bank of France, the Swiss National Bank, and others.

They say it’s an experiment… one that leverages Curve’s AMM technology. It’s like we can literally see them understanding how these AMMs work and how certain AMMs are better for different use cases in real-time.

To quickly sum up what Mariana is about… It enables the transfer of tokens (what it calls “wCBDCs” on the network. Central banks can print and add liquidity, then commercial banks can use the wCBDC tokens for transactions with the AMM and other banks.

Think of it as a permissioned mint contract for central bankers where commercial banks can interact with the AMM.

Common words used in these explanations are “security,” “cross-border,” and “efficiency.” Nothing wrong there by any means.

But what is missing here is, what happens to the U.S. dollar as the conduit for trade?

We all know that AMMs are more about transferring without needing dollars or even ETH in some instances. Meaning it will reduce reliance on the dollar to conduct swaps and transactions.

To say it another way, the stat from earlier of the dollar being involved in 88% of all foreign settlements is 100% in jeopardy.

The case for BW3 is gaining traction.

The Next Source of Inflation

Everybody hates it when I go down a rabbit hole of research.

When I surface, I start to talk in a second language: academic speak.

I vividly recall my time writing academic papers. And as I look back on those pieces, I can’t help but think how stuffy I sounded.

It’s also really hard to understand. Which is why these rabbit holes rewire my brain for a few days. But the reason I was binging on these papers is I wanted to see if anybody was researching what might happen if dollars are less in demand.

What would be gold is if somebody was pairing this up with the new AMM tech.

I found quite literally nothing… Except two papers from the IMF.

The first one is “Digital Money and Central Bank Operations.” The second was “Falling Use of Cash and Demand for Retail Central Bank Digital Currency.”

The title of the second one should really give the topic here away. The papers discuss how the transition from physical cash to digital alternatives changes the dynamics of monetary policy and inflation.

To speak plainly, the authors are discussing CBDCs and inflation. What I like about their approach is they discuss two outcomes.

First, the authors hit on the manner in which the rise in usage of digital banking services and nonbank alternatives to cash will reduce demand for physical cash. To paraphrase while also using some of their terminology…

This shift impacts the ratio of cash outstanding to GDP and broader monetary aggregates. The movement from bank deposits to e-money will reduce broader aggregates if there are no requirements to hold reserves against e-money (aka physical warehousing of digital forms of money).

What they are saying is there need to be certain capital controls in place.

Otherwise, we get the second outcome: In economies where regulations require holding reserves one-for-one against e-money, the movement from cash to e-money will have no effect on broader aggregates.

All this is referencing what is known as “shadow banking.” It’s part of the money system that falls out of the purview of money supply. Fintech platforms that allow you to borrow money even account for this world.

It’s suggesting that these non-CBDC forms of money could reduce usage of dollars, and in turn create inflation.

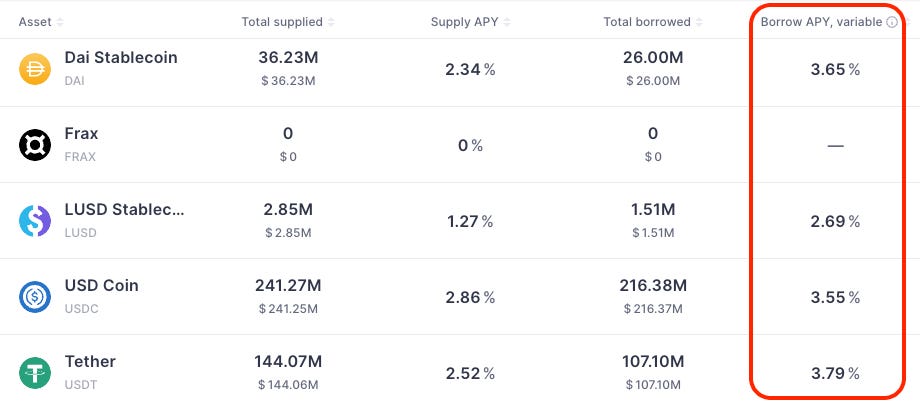

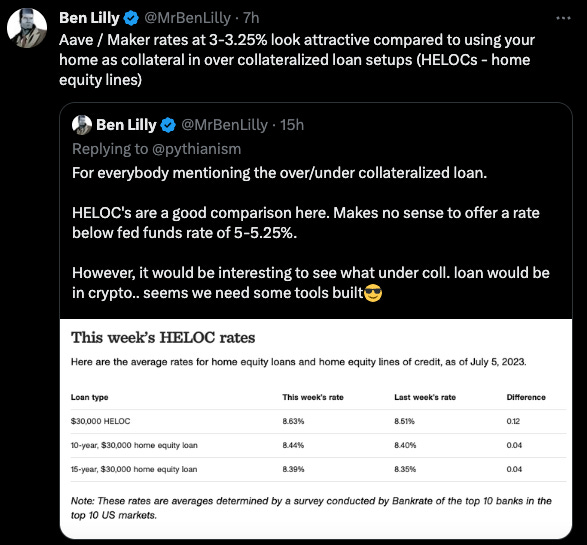

For crypto degens… If borrowing tokens in an overcollateralized manner using Aave is offering this…

While you are going to the bank to use your home as collateral to borrow money at these rates…

Where would you go?

Hopefully, you see that this can spell trouble for the Fed, which is trying to set the cost of capital. These other forms of the dollar – DAI, USDC, USDT – that are not printed by the Fed will be used, and that will quite literally create interest rate issues that the Fed is trying to control.

And it will lead to less demand for actual dollars… and higher inflation.

It’s interesting to think about this problem. And in some ways, I understand why the new guidelines for Basel will be coming out soon. These guidelines tell banks how much capital they need to hold in their vaults for their business practices. It addresses this sort of issue mentioned above.

So we should expect stablecoin guidelines to fall in line with this sort of thinking… Otherwise, they do in fact undermine what the Fed is trying to accomplish.

Before I get hate mail on my pro-Fed regulation stance, I want to say that U.S. dollars are theirs. Making our own version of U.S. dollars is us just copying their invention. We have native tokens… Maybe we just create additional stability in those instead of getting all upset over stablecoin regulations.

But before I go off on too many tangents, I’d like to really drive home the point of bringing up this discussion on money demand and inflation…

These papers don’t reference the potential drop in demand for money in relation to the push-out of new FX swap technology like Project Guardian and Project Mariana. I’m curious when these entities address this, as I’m sure somebody at the Fed, BIS, or IMF is thinking about it.

This should be a major concern not just in the U.S., but globally. It acts as the catalyst to what looks to be a hidden tsunami of inflation.

What a time to be alive.

Your Pulse on the Dollar*,

Ben Lilly