Jan 15•6 min read

About That 2021 US Rebound - Corporate Investment

There are three possible drivers for a post-covid 2021 US economic domestic rebound: household consumption, business investment, and fiscal stimulus. The previous piece looked at the current data which cast doubt on the likely strength of the immediate post-covid economic rebound. Today's piece looks at the potential for a surge in business investment to drive the rebound. It's conclusions are similar: in the circumstances which are currently visible, it would be unlikely that corporate capital spending will be a strong driver of US recovery.

Industrial Investment & Capacity Utilization

The problem is that the usual metrics which ought to anticipate and drive business investment are exiting 2020 in poor shape. Starting from the most obvious: capital spending tends to rise when current productivity capacity is pushing against its output limits. But when we look at industrial capacity utilization rates, by December, they are clearly in recovery, rising 1.1pps to 74.5%, which is the highest since March. But by historic standards this remains very low: between 2012 and pre-Covid 2020 capacity utilization rates averaged 77.3%, with a standard deviation of 1pp. In other words, at the end of 2020, capacity utilization rates were running 2.7 standard deviations below average historic levels. On the face of it, it seems unlikely industrial investment will lead the recovery.

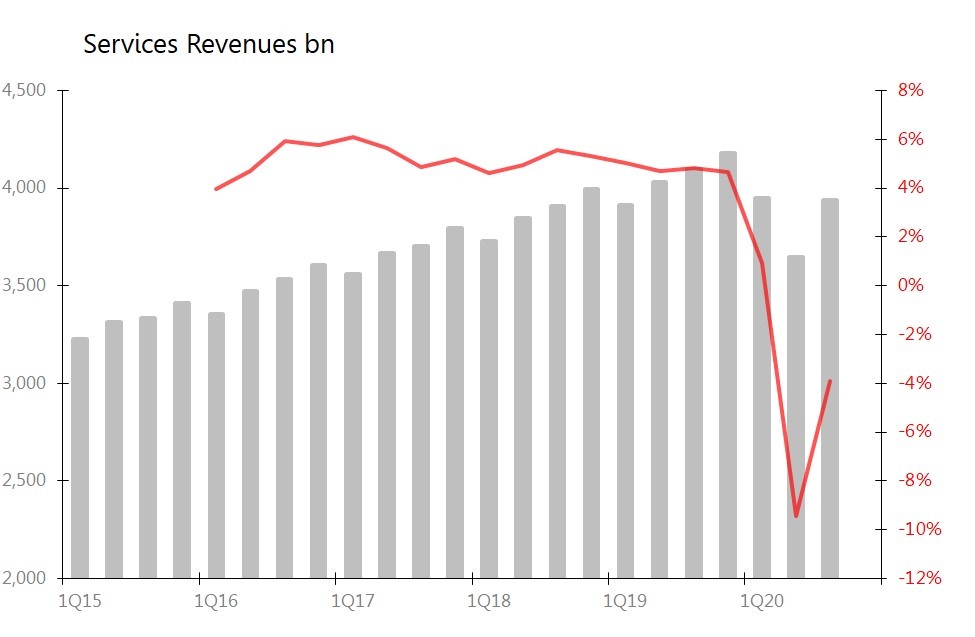

But the US is not primarily an industrial economy: in 2019 services accounted for 46.8% of nominal GDP, whilst consumption of goods accounted for only 21%. Similarly, investment in industrial and transport equipment was responsible for only 20% of private non-residential investment spending. Moreover, as we argued in the previous piece, the argument for a rebound in services spending during 2021 is stronger than for retail spending. Still, since services spending had sharply outperformed long-term trends in 2018 and 2019, a rebound simply to trend levels would cap spending growth at around 6.2% in 2021.

Services Investment - Surprisingly High Hurdles

During Jan-Sept 2020, services revenues fell 4.2% ytd, and if one pencils in a 1SD recovery in 4Q, revenues for the year will have fallen approximately 3.6% for the year. The pre-covid trend rate of growth was running at around 5.1%, according to the quarterly survey of service sector revenues. If revenue growth rebounds by 6.2% in 2021, this will still leave it 7.3% below the nominal levels one would have expected 2021 revenues to have been had the trend growth rate of 5.1% been maintained throughout 2020 and 2021. Simply in order to match the revenue levels one would previously have expected in 2021 would require a rebound of 14.6% during 2021.

At that level of revenues, one would expect that demand shock inflicted by the pandemic on service-sector capital stock to be neutralized. At that level of revenues, one could expect new service-sector investment spending to be necessary to service current demand. But how likely is revenue growth of 14.6% in 2021?

Certainly personal savings have risen during the pandemic: by November they were put at $2.22tr. This is just under $1tr higher than in November 2019. By comparison, if service industry revenues grow 6.2% in 2021, this will be a nominal rise of $970bn yoy. If services industry revenues were to grow the 14.6% needed to 'catch up' with the falls of 2020, the rise required in 2021 would be $2.28tr yoy. In other words, running down the savings accumulated during the pandemic won't be enough to restore service revenues to the sort of levels where a bolt of investment spending should be expected.

Using the data about actual dollar amounts available, the case for expecting a dramatic rebound in capital spending is unexpectedly difficult to make. But in addition, a signal which I have used for years in a wide range of economies also suggests caution.

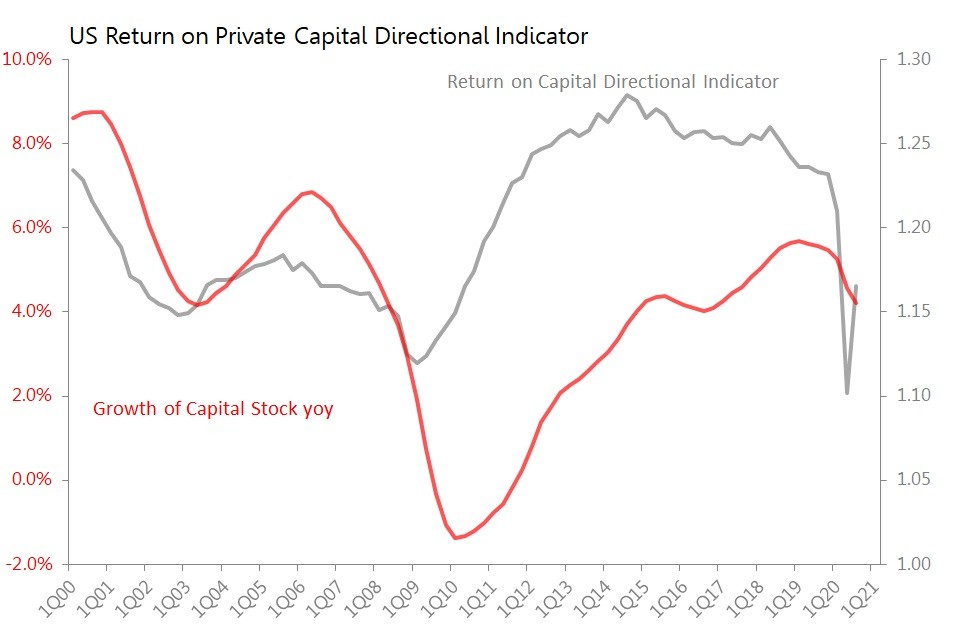

Return on Capital Directional Indicator

That signal is my Return on Capital Directional Indicator (ROCDI), which treats nominal GDP (less inventory changes) as an income from a stock of fixed capital. That capital stock is then estimated by depreciating over a 10yr period all nominal gross fixed capital investment recorded in the quarterly national accounts. One can think of the ROCDI as a sort of 'asset turns' measurement for the economy as a whole. And the crucial thing to know is that directional changes in the ROCDI regularly precede changes in the growth of capital stock. Not surprisingly, if returns on capital are rising, then eventually capex rises and capital stock growth accelerates; when return on capital falls, then - eventually (bull markets often last longer than their economic justification) - capital stock growth slows. The regularity of the relationship is discovered quicker on the way up than on the way down.

Here is it in action since 2000:

The current situation does not suggest a rapid rebound in capital spending, for two main reasons. First, of course, even with the rebound already seen in 3QGDP, the level of the ROCDI is still hardly better than at the worst moments of the GFC. Second, the growth of capital stock was already slowing prior to the onset of the pandemic, in response to a downward drift in ROCDI seen since 2014. The slowdown in capital stock growth set in in the middle of 2019, and the trauma of 2020 merely accelerated that fall.

But this is not a purely negative indicator of doom. The recovery in ROCDI during 3Q, if maintained, does suggest that the slowdown in capital stock growth will bottom out in the second half of 2021. What is in doubt is the strength of that rebound.

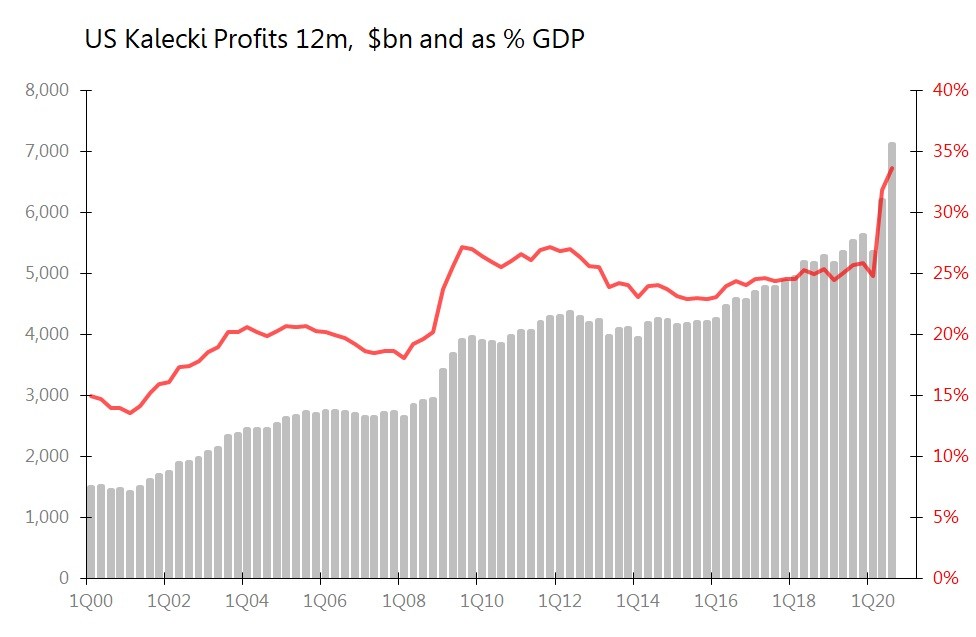

Kalecki Profits - A Counterintuitive Signal

The final signal is distinctly counterintuitive, at first glance providing an extraordinary reason why we can expect a major rebound in capital spending. The signal is the surge in Kalecki profits seen during the 2020 pandemic. This is counterintuitive in two ways: first, because a surge in 2020 profits runs counter to every obvious expectation, and every published narrative. Second, because we should not expect the surge in profits during 2020 does not, in fact, herald a joyous outbreak of capital spending in response.

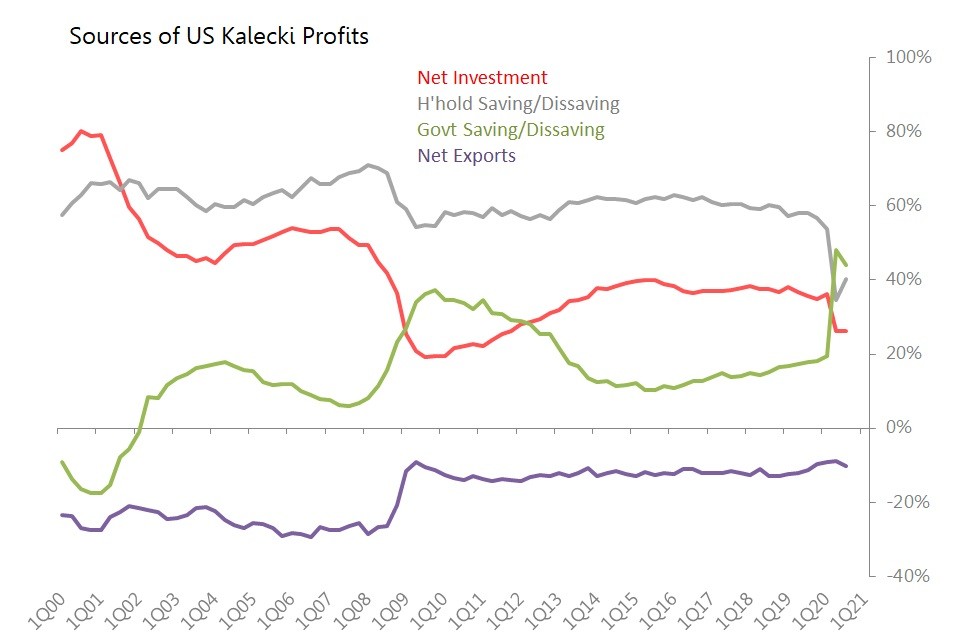

The reason for both these unlikely results is the same: the profits of 2020 are anomalous (ie, exceptionally unusual, breaking usual 'economic laws' because of the extraordinary rupture in their attribution. To an extent previously unseen, the rise in 2020 Kalecki profits is attributable almost solely to government deficit spending: in the 12m to Sept 2020, the federal deficit jumped $2.148tr yoy to $3.132tr, whilst Kalecki profits rose only $1.590tr yoy. All other measures of savings/dissavings fell: net investment fell $110bn, household dissaving fell $346bn, and the trade deficit widened $102bn.

Only if companies expect government fiscal deficit spending to be maintained at 2020 levels, or increased, would they be confident that the Kalecki profits of 2020 can be repeated in 2021. More specifically, only if they believe that an increase in household dissaving and/or an improvement in the trade balance can compensate for any shortfall in the contribution of a moderated fiscal deficit (or moderated rate of growth of the fiscal deficit) are they likely to increase net investment spending.