Aug 06•5 min read

The Valuation Project - Part 2, the UK

I set out to construct a reasonable valuation framework for stockmarket indexes which abandonned the concept of 'risk free rates' in the light of central banks' dramatically increase influence on those rates. For that framework I set two tests:

1. Ought the method work - ie, does it seems a priori a reasonable approach;

2. Does it actually work - ie, are its results confirmed by actual stockmarket performance over the long term?

In Part 1, I offered the idea that a fair valuation for a capital asset would be one in which the stream of profits would allow it to maintain its position relative to the economy. If so, by extension, a fair price/earnings ratio ought to be determined by the long-term average nominal growth rate of the economy, with a premium determined by the volatility of that growth rate. In addition, for a representative stockmarket index, the profits are taken as the profits of the entire economy, as estimated by the Kaleckian methods, rather than the selectie profits of the listed companies.

This, I thought, ought to be the way markets value assets. More, it turned out that for the world's leading market - the US and the S&P 500 - not only should this work, it also has provided a good long-term guide to how the stockmarket index price has actually changed over the last 30 years. It thus satisfied my two tests.

That it works in the world's leading economy / leading stockmarket index is a good start. But does it work for other major economies, other major stockmarket indexes? Let's start with the UK and the FTSE 100.

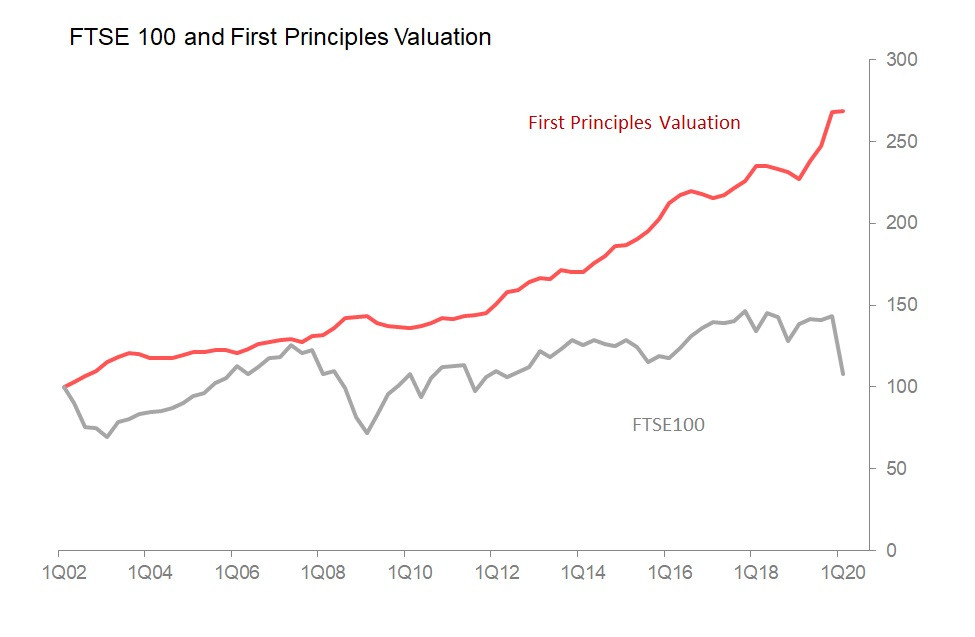

At first glance, it is clear that there is something fairly disastrously wrong - this method does not work for the UK, with the FTSE 100 index not only dramatically underperforming in the long run, but also seeming to bear no interesting directional relationship with the fluctuations in my estimate of fair value either.

At this point, one can either give up, or start to wonder what is wrong. Given that the first principles valuation looks very useful for the US, giving up seems less interesting that questioning what it wrong. And my first observation is that it may be unreasonable to expect the FTSE 100 to respond to the underlying conditions of the UK economy, since its constituents are not representative of that economy in the first place. Even if the UK shared the same economy as London, the FTSE 100 would not really claim to represent either the UK or even London. Indeed, London sees it as a matter of pride that it is a global financial centre, and as such it hosts a global index.

This is made more likely by the fact that the first principles valuation from UK data which fails for the FTSE 100 works far better for the more UK-centre FTSE 250.

This is an improvement, albeit over only a 10yr period, which is shorter than I would like. For the two questions I need the argument to satisfy - should this valuation work? does it work? - the answers are 'yes, stronger than for the FTSE 100, but weaker than for the US and S&P'.

But the fact that this first principles valuation does seem to work reasonably for the FTSE 250 also adds weight to the possibility that the FTSE 100 is not fundamentally reacting to British conditions because it is not fundamentally a British index. And this leaves open another possibility - that as an international or global index, it is responding to the predominant global investors' demands, which in means the demands of the US-dominated global investment houses.

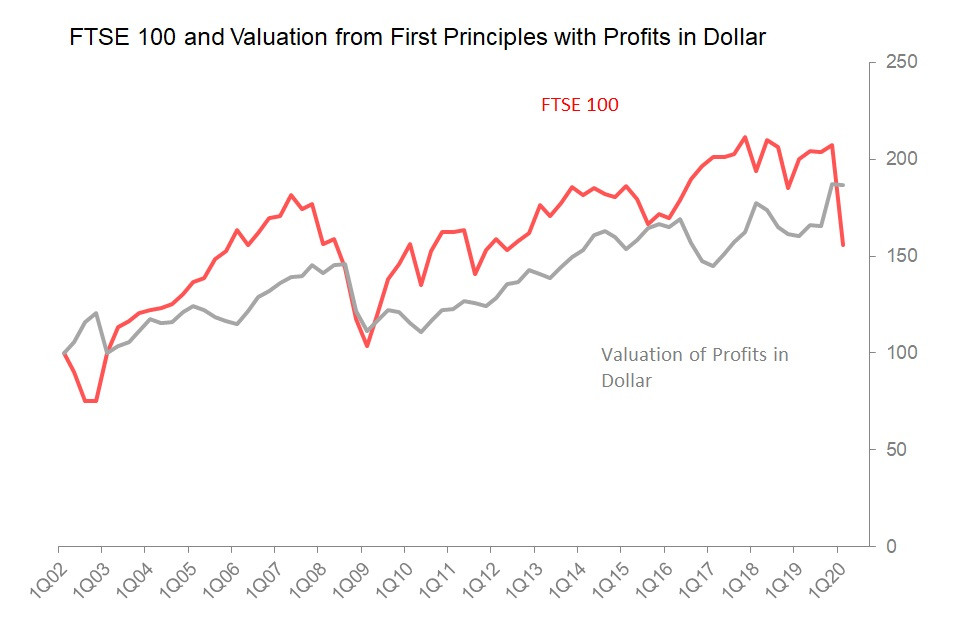

What, then, if we construct a first principles valuation for the FTSE 100 simply denominating the Kalecki profits in dollar, rather than sterling. Already this first principles valuation appears to track actual index performance reasonably well.

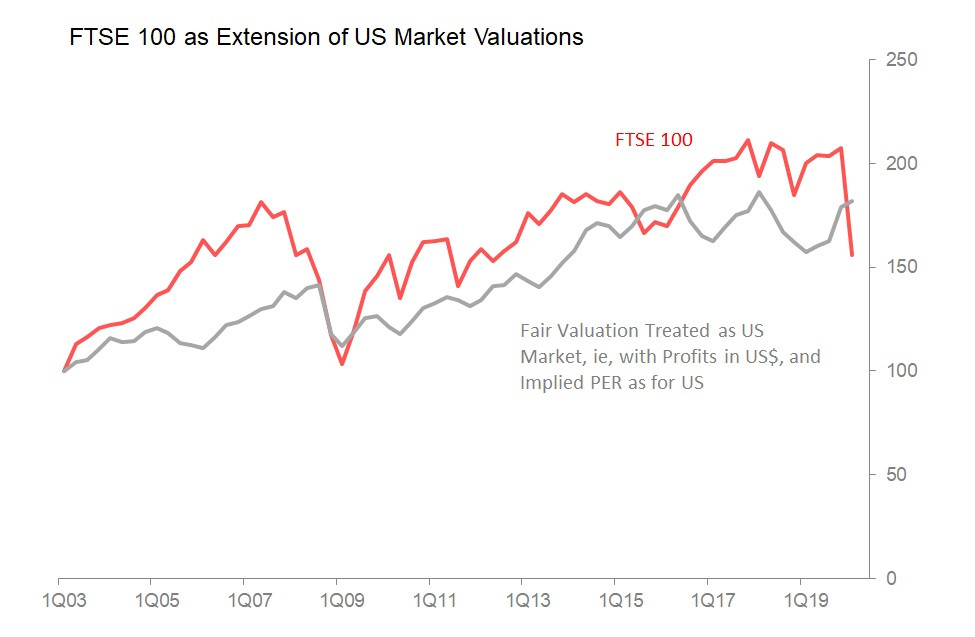

And we could, and perhaps should, go further, not only restating Kalecki profits in dollars, but also using the PER indicated by the long-term nominal growth rate and volatility of the US economy, rather than the UK economy. To a patriotic Brit, this may seem to confirm the degree to which the UK markets are a colony of those in the US. Though this may offend the proprieties, is this not likely? In the end it doesn't make a great deal of difference: in both cases, the result tracks the actual performance of the index far better than our initial valuation, and has done for approximately 17 years now.

To return to my two conditions: to be accepted as reasonable, the model should be roughly right, and in practice must have been shown actually to be roughly right. For the FTSE 100, I think this interpretation of the the model has actually been roughly right, but the question remains open as to whether it should be accepted as the way London's international equity market works.