Jul 23•6 min read

John Gray, Pessimism and Cultural Challenge

The philosopher and historian John Gray asserts in a recent extended interview that we are going through a period of change even more dramatic than the fall of communism in 1989/90, laments that this could be the death of western liberalism, and that there will be no restoration of the world we have been used to living in.

If he is right, then we had better get on with discovering adaptations to a new world we don't really yet understand, or see. But is he right?

Gray identifies current disatisfactions with the re-assertion of nationalist and religious forces which had been quietly de-emphasised or dismissed during the period of post-war liberalism. A combination of nationalist and religious forces were, he thinks, fundamentally what did for the USSR, and what are now doing for the post-Communist liberal worldview.

He identifies the current 'hyperliberalism' as being fundamentally a religious movement bearing a secular gloss. It is hard to disagree: the denunciation of our original sin, the heresy-patrols of language, the witch-finding, and the overt symbolism involved in the BLM movement (taking a knee, washing the feet) are all recognizably religious phenomena.

Similarly, the reassertion of the nation as the fundamental unit of political identity is visible everywhere, with Brexit being merely the fore-runner of unresolved and probably unresolvable tensions within the 'European project.'

But he extends this, and perhaps confuses it, with a larger argument about the downfall of the US as the world's hyperpower and hegemon. The re-emergence of separate forms of civilization (China, Russia, India) he evidently views as the collapse of universalist dreams allegedly held by liberals. As a result of this loss of liberalism's universalist illusion, there can be no going back to the world as it was before the cultural tremors of 2020. Rather, we are likely to revert to a rather late 19th century situation, a world he characterises of one of anarchical states and great political change.

I think most of this is open to question, but Gray is at his best and most persuasive with his insight that liberalism as we know it was born in the aftermath of Europe's 16th century wars of religion, when it emerged as the way of allowing people of fundamentally different religious views to co-exist without persecuting or killing each other. The necessary values he identifies are tolerance, freedom of enquiry, and the importance of truth as fact - ie, that truth is not a construction of a political project or a religion.

It is precisely those values which are under attack in today's 'hyperliberalism'.

But I wonder whether his analysis, which overtly downgrades and even ignores the influence of economics on how soceities develop, is correct. Who in the 'liberal west' truly believed that liberalism and free markets would sweep the world and thus 'end history?' Francis Fukuyama, momentarily. A small number of discredited Western leaders (Blair, George W Bush . . . ) perhaps. But there are many thousands of people with experience of living in China, Japan, India, Indonesia, Thailand, S Korea who can have had no illusions that these countries were, or were ever likely to be, identical to, say, the UK or the US. That was obvious even when you were lodged in the same 'global' hotel-chains and paying with the same credit-cards. Japan, for one, is a spectacular and enduring testament to the possibility that great wealth, and great technological achievement (the underpinnings of great modernity) need not necessarily efface distinctive local cultures.

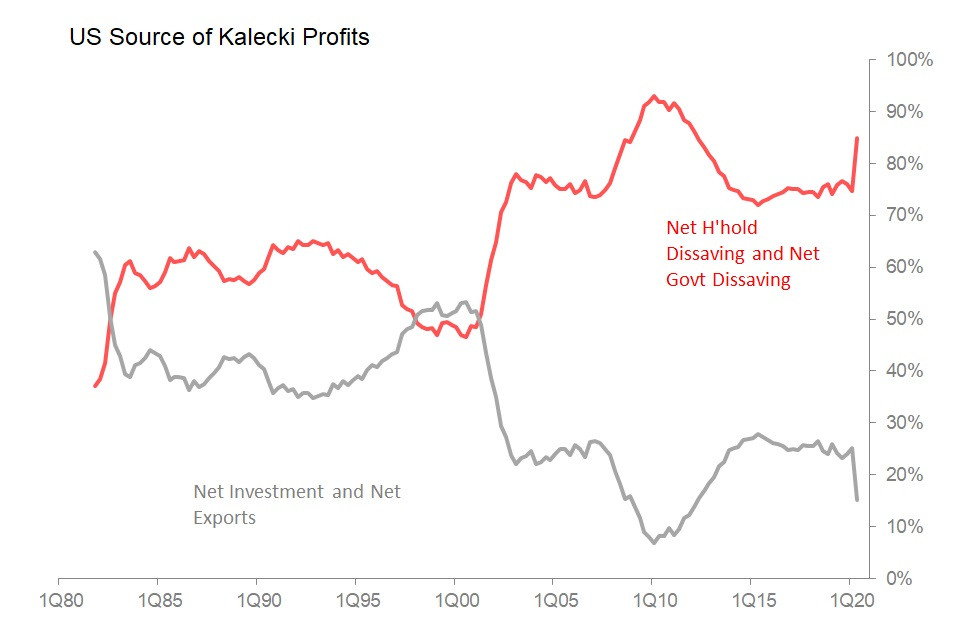

Cutting out economics from the analysis also seems unwise, since so many of our dissatisfactions in Western socities are clearly linked to our current distortions of the 'free market'. These distorted structures have not only stymied investment, productivity and real wage growth for most people, but worse, have deepened inequalities of wealth and income at the same time as making continued corporate profitability dependent on the beggary of households and governments. This is something which I have calculated and illustrated repeatedly over the last couple of years, noting that this structure is not inevitable or even historically common - rather it is a historic and geographic anomaly which can, should, and will eventually be dealt with by political choices which remain completely compatible with the 'free market'.

And third, I question whether the religious instinct driving the current hyperliberalism will either be accepted in the US, or even whether it can sustain itself for long. The underlying weakness of totalitarianism - religious or not - is, after all, that the political and emotional enthusiasm on which it depends is exhausting. It also remains to be seen whether the current seemingly irresistable torrent of US hyperliberalism will be endorsed and embraced by the US electorate. I have my doubts. As Saul Bellow observed about the US: 'Anyone who wants to govern the country has to entertain it'. Say what you like about hyperliberalism, it's strict seriousness doesn't entertain.

None of this is to deny that after the coronavirus the policy assumptions and stances which have prevailed in the US and UK for the last 30 years or can or should be restored. Back in January 2019, I wrote a long piece called 'End of Days' which argued: 'the assumptions and policy reactions underpinning economic policy, and generating outcomes both for the economy and for financial markets, are exhausted. Rather than solving problems, the default conventional wisdom is now compounding problems. As a result, the incentive structures within which we think and work, currently are more likely to result in bad choices rather than good ones. Our attempts to project a future based on those familiar stimuli and familiar assumptions, are likely to be either ineffective or, at worst, actively mislead us.'

That piece was followed by others which went into the details of the illusions which had led us towards the End of Days. For reference look at 2019: Funk, Lies & Displacement Activity , and 'Our Times: Where it All Went Wrong'

But quite obviously, if you can identify the problem, you are half-way to discovering solutions. In the case of the recent US and UK economic models, it is not even particularly difficult to see how a different set of policy priorities could allow these countries to reverse out of the previous exhausted model. The British public, in particular, has found no great difficulty in rejecting both the failed policy-prescriptions imposed by the European Union and the dullard's set of alternative policies suggested by the Labour Party. I think Mr Gray has left out one absolutely crucial aspect of liberalism which unites the social, technical, political and economic characteristics of liberalism as it has developed since Europe's wars of religion. That is its practical commitment to discovery. At this stage, there seems no good reason to believe that western democracies cannot and will not discover ways to address current dissatisfactions which fall short of their own destruction or even eclipse.