May 30•8 min read

Revolutionizing Art with Ordinals: Crafting Inscribable Masterpieces through Adaptive Creativity

Bigger is always better. From larger screens and higher pixel counts to bigger SUVs and houses, the desire for size is ingrained in our culture, especially in ‘Merica. However, it's important to recognize that bigger doesn't always equate to better. Many of my doomed millennials mates are now finding fulfillment in downsizing, choosing tiny houses, and challenging the consumerism accommodated by larger homes. Many are doing a Marie Kondo-inspired reappraisal of all the things that reside in their overstuffed dwellings, and ditching anything that, upon clutching close to one’s heart, does not “spark joy.”

Interestingly, this less-is-more approach aligns with the digital collectibles space following the release of Casey Rodarmor's Ordinal theory earlier this year. Faced with scarcity and the increasing value of limited blockspace, creators are compelled by necessity, the mother of invention, to explore imaginative ways of accomplishing more with less. The main focus of this article is to provide some examples of how I have explored compression techniques in my creative process, particularly in the realm of music videos. My largest and most ambitious ordinal is "Digital Enigma," a 20-second music composition that serves as both a stand-alone music composition, and a musical binary puzzle. But first, here’s a quick tl;dr on Ordinals:

Ordinals are a protocol that enables the creation and storage of non-fungible digital assets on the Bitcoin blockchain. Each ordinal consists of a marked satoshi (the smallest unit of Bitcoin) and an associated inscription. By allowing for the existence of NFTs (I prefer the term “digital artifacts”) on Bitcoin, ordinals enhance the value and utility of the network, attracting more participants and reinforcing Bitcoin's position as a store of value.

Currently, Bitcoin blocks have a theoretical maximum size of 4 megabytes, and new blocks are added to the blockchain roughly every 10 minutes. If you look at the mempool, most blocks are between 1.4 and 2 megabytes, but Udi Wertheimer made waves (and many maxi’s cry) when he collaborated with Luxor Technologies and mined the largest block and largest transaction in Bitcoin’s history by inscribing a Taproot Wizard jpeg.

The limited block space becomes a concern when there is a high demand for including transactions and other data on the blockchain. When the block space is congested, transaction fees tend to increase as users compete to have their transactions included in the limited space available. Miners prioritize transactions with higher fees because they are economically incentivized to include those transactions in the blocks they mine.

Miners receive both the block reward (currently 6.25 bitcoins per block) and the fees associated with the transactions they include. Higher fees incentivize miners to prioritize certain transactions, as it increases their potential earnings. Therefore, when more users want to use the limited block space by submitting transactions or storing additional data like ordinals, the increased demand drives up transaction fees. This increase in fees serves as a mechanism to regulate and allocate the limited block space efficiently. Miners benefit from higher fees, as it directly contributes to their revenue and incentivizes them to continue securing the Bitcoin network. On May 7th, the transaction fees (6.7 BTC) were greater than the block subsidy (6.25 BTC), and as the block subsidy continues to be cut in half roughly every four years, miners will rely more and more on fees.

You may be asking, “Yo, Longstreet, wasn’t this supposed to be a tl;dr?” Fair enough, let’s move on. Limitation requires innovation, and it’s worth checking out work by Pryzm.btc and Boozy.btc with Counterfeit Culture, JimdotBTC from ThisIs#1, Alexander Rudloff, On Chain Monkey, Megapont, The Guests, and Nonnish for great examples of how artists are creating amazing pieces that are small in size. I’m sure there are more, but these are the projects I’m most familiar and impressed with.

The use cases for me have been many. I’ve inscribed images that hold personal/sentimental value, single-image representations of collections released on stacks, one-of-one art (auctioned of with Neoswap), and songs that hold cultural significance (happy birthday, and the first recorded sound dating back to 1860). I might even inscribe this article after it’s published.

I hold tremendous admiration for the artists who have skillfully adapted to meet these evolving demands. While exploring numerous use cases has been rewarding, I must honestly admit that a sense of dissatisfaction lingers within me. Most of my collections, notably in collaboration with the Airdrop Podcast, Project Indigo, Nonnish Kingdom, and Dr. Suss & Boozy, involve music visualizer videos released on Stacks. These files typically range from 4 to 12MB in size. Even after attempting various file conversion methods, I realized that they still couldn't be compressed sufficiently for inscription. It became evident that considering these limitations from the outset was imperative. My new objective was to create a music video that could realistically be inscribed without incurring exorbitant costs, while still maintaining an acceptable level of visual and auditory quality.

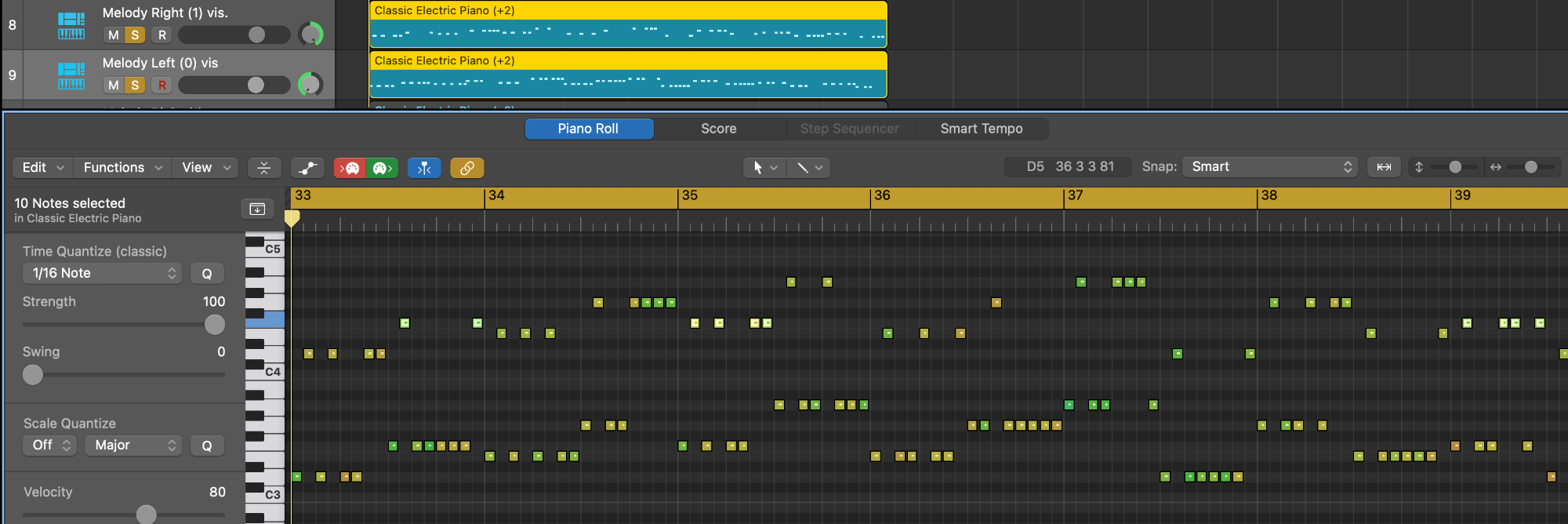

Let’s start at the very beginning, a very good place to start. Simultaneously, I aimed to craft a musical puzzle, leading me to conceptualize the representation of binary code in a musical form. To achieve this, I utilized a text-to-binary converter and inputted the notes manually using a MIDI keyboard. The note C3 represented 0's, while C4 denoted 1's, creating an octave difference between the two. To enhance the distinction, I panned the notes hard left and right, which you can hear especially well when listening with headphones.

With great care to avoid mistakes (as corrections are not feasible once inscribed), I sought ways to infuse melody into the composition, rather than settling for monotonous beeping for a mere 20 seconds. Given that binary code consists of eight digits per letter, it naturally lent itself to musical patterns. I assigned a rhythmic value of one 1/16th note for each digit, resulting in eight digits every two beats. As the answer for this enigmatic puzzle encompasses 16 letters (64 binary digits), this fortuitously created a perfect 8-bar phrase of 16 half notes. If you want to know the answer, scroll to the end of the article.

Once I cracked the code of representing binary in a melodic manner, the next step was selecting the appropriate sounds. Considering the need for maximum compression, I opted for tones that would retain authenticity even under heavy compression. The perfect solution came in the form of 8-bit video game synthesizers. This choice mirrors the trend among artists who employ pixel-style art that, despite its small file size, can be effortlessly scaled up. Pixel art and "chiptunes" not only follow the current trend but also evoke a delightful sense of nostalgia.

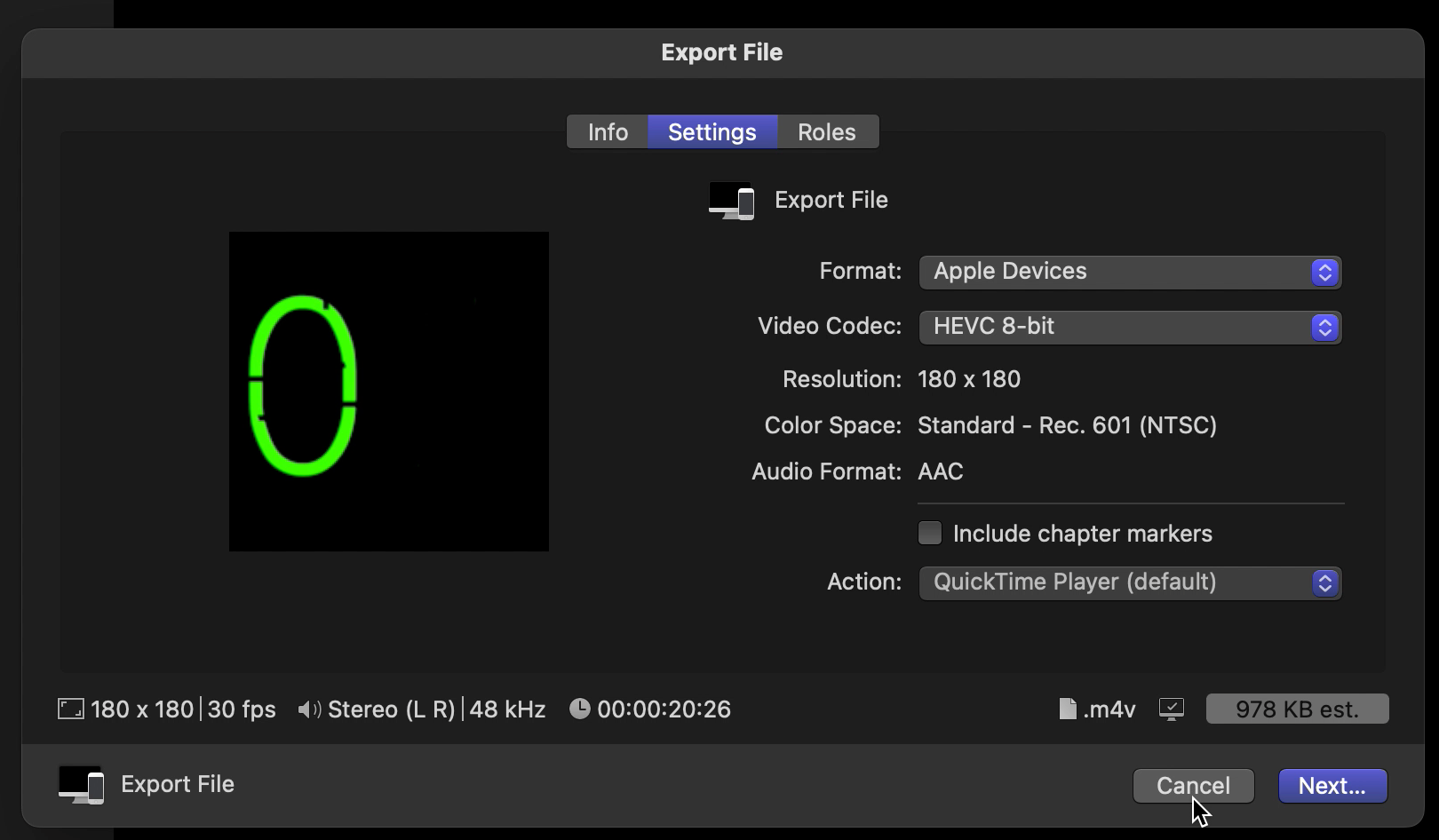

When the song was done I used Final Cut Pro X to make the visuals and set up a project with custom dimensions of 180 by 180. After accounting for all 0’s and 1’s (and checking multiple times for any mistakes) I exported with the following settings:

Export to Device -> HEVC 8-bit -> Action -> Open in Quicktime

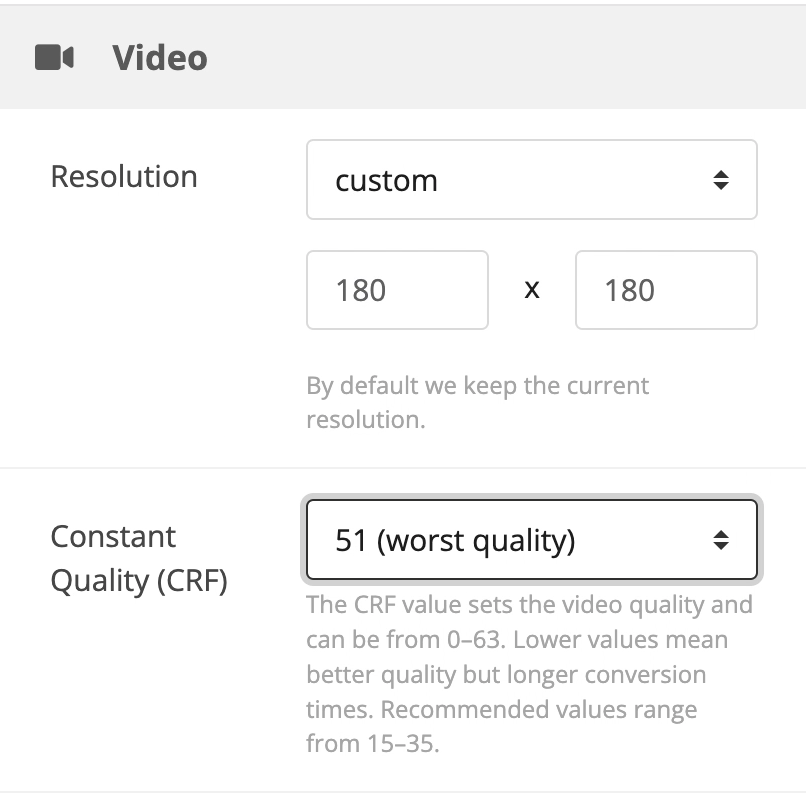

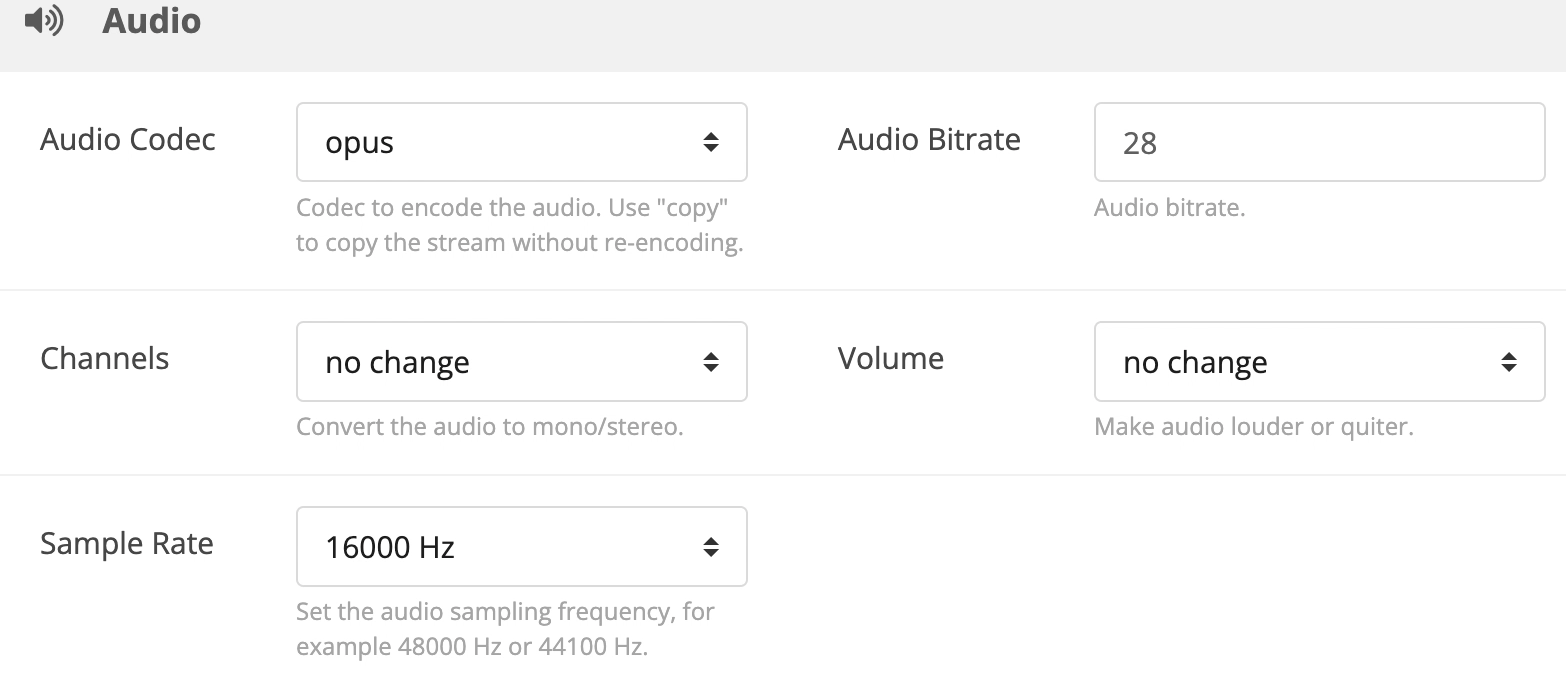

Then I used Cloud Convert to convert an MP4 to WEBM, and this is where a lot of the trial and error was done to get the file as small as possible without sounding horrible. Ultimately I found the following settings to be the best compromise:

Custom 180 x 180 resolution

Constant Quality 51 (worst)

Sample Rate 16000 Hz

Audio Bitrate - 28 (this is the sweet spot)

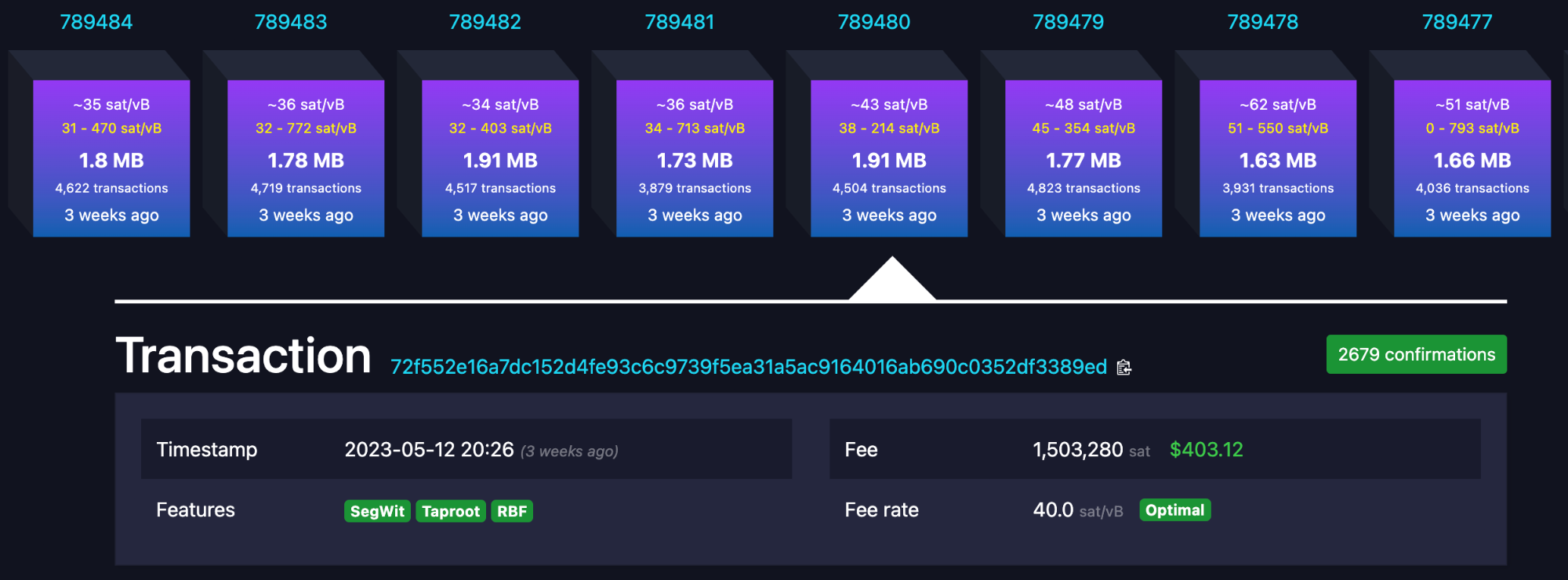

And with that I ended up with a file that was 149kb, which was still quite costly to inscribe: 1,503,280 sats at 40sat/vb.

Art is a subjective realm, and personally, I find immense fulfillment in having my creations forever etched onto the digital cave walls of the Bitcoin blockchain. However, this pursuit comes with a challenge—the fierce competition for blockspace. It acts as a barrier to entry, forcing artists to carefully evaluate whether their work is truly worth the associated cost. I am delighted to share that as of today I have sold enough of the 42 Digital Enigma 1/1's on Stacks to recover the cost of inscription. This model has proven to be a promising approach that could also benefit other artists.

I would like to express my heartfelt gratitude to Jamil, Nick, and Brett from Gamma.io for their invaluable assistance in numerous projects. Their unwavering commitment to supporting and prioritizing artists has been truly commendable. I wholeheartedly recommend utilizing their creator portal for all your inscription requirements. Their support and dedication make them an excellent choice for artists seeking reliable solutions.

Big shout-out and thanks to the following members of the Stacks community who were the first five to solve the puzzle, and who received the first 15 of the 42 Digital Enigma 1/1’s on Stacks. Franscisc.btc, KillerKrayon.btc, Abreu.btc, Ocra42.btc, and fireflywash.btc

01010011 01000001 01010100 01001111 01010011 01001000 01001001 00100000 01001110 01000001 01001011 01000001 01001101 01001111 01010100 01001111

You can reveal the answer by copying this binary into the binary-to-text converter.

I sincerely hope that by sharing my experimentation and creative process, I can contribute to your own artistic endeavors. In the spirit of the 2023 Ordinals Conference, where Bitcoin entrepreneur Ragar Lifthrasir imparted his wisdom, let me ask you: "What will you inscribe?"

May this question inspire and guide your creative journey.

A Year of NFTs on Stacks: Reflecting on My Evolution as an Artist

Songs from Kirot Dün - Longstreet & Nonnish

Keeping an Open Shutter - Motion Blur Photography